Download Print-Friendly Version

Download Print-Friendly Version

Whenever we talk about Thanksgiving and its origins, we refer to the first Thanksgiving in 1621. We talk of the Pilgrims and Wampanoag and the great feast they had together, celebrating the abundant harvest which was, in great part, thanks to the Wampanoag’s help. That is a part of our past well worth remembering. But there is actually another Thanksgiving story, equally important, which we don’t often recall. And this story includes an important founder of our nation who is likewise unfamiliar. This story, the first Thanksgiving under the new Constitution, had nothing to do with harvests or Pilgrims or American Indians. But there is actually another Thanksgiving story.

[Boudinot] could not think of letting the session pass … without offering an opportunity to all citizens of the United States of joining, with one voice, in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings he has poured down upon them. With this view, then, he would move the following resolution:

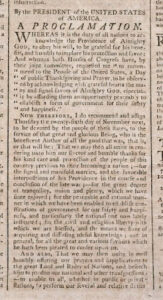

Resolved, That a joint committee of both Houses be directed to wait upon the President of the United States, to request that he would recommend to the people of the United States a day of public Thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.

This Thanksgiving proclamation would not be a reminder about great harvests or friendly people. This Thanksgiving would be about the Constitution, its new form of government, and the peaceable way it came about for everyone’s protection and happiness.

Surprisingly, only a month before, President Washington himself had written to James Madison, mentioning that he was contemplating asking the Senate to implement a day of Thanksgiving. However, this proved unnecessary, as Boudinot, feeling the same way, initiated the process in the House of Representatives.

After some debate about the appropriateness of this idea and whether they had the power to put forward such a resolution, Representative Roger Sherman, a Congressman from Connecticut, as well as a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, spoke in agreement with Boudinot. He felt the resolution was justified and reminded them of the long tradition of calling for a day of Thanksgiving. In fact, having a day of prayer and Thanksgiving, or even fasting, prayer, and Thanksgiving, was common. Sherman reminded them that it was more than just a routine practice in the colonies. The idea actually extended all the way back to the Old Testament times after King Solomon finished building the Temple.

Representative Roger Sherman, a Congressman from Connecticut, as well as a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, spoke in agreement with Boudinot. He felt the resolution was justified and reminded them of the long tradition of calling for a day of Thanksgiving. In fact, having a day of prayer and Thanksgiving, or even fasting, prayer, and Thanksgiving, was common. Sherman reminded them that it was more than just a routine practice in the colonies. The idea actually extended all the way back to the Old Testament times after King Solomon finished building the Temple.

Boudinot’s resolution passed. Within just a few days of receiving the resolution, President Washington issued the proclamation. It was subsequently published in newspapers throughout the fledgling nation.

Perhaps the first Thanksgiving held here on the North American continent was for the Pilgrims to celebrate a great harvest with their American Indian friends. But the first Thanksgiving held in these United States was actually to give thanks to God for His help in establishing the new constitutional form of government through peaceful means. This story of the nation’s first Thanksgiving is less remembered today. And knowledge of a key catalyst of this Thanksgiving has largely disappeared from view. Who was this man, so intent on ensuring that God be given proper appreciation?

Elias Boudinot (pronounced Boo’-din-oh) is by no means a household name in the United States today. His personal legacy as a U.S. founding father has faded from public view. This neglect is unfortunate, considering the important roles he played during the country’s founding. This Thanksgiving would be about the Constitution.

In 1772, Elias was appointed as a trustee of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). Not long after this appointment, however, rumblings of the coming revolution began to spread throughout the colonies, and Elias was swept up in the cause. While he felt that many of Britain’s actions toward the colonies were unjust, he initially hesitated. But once it was clear that the war of independence was inevitable, Boudinot was all in.

In the spring of 1777, Gen. Washington commissioned him to serve as Commissary General of Prisoners. This position ended in 1778, when he was elected to the Continental Congress, where he served for a year. In 1781, he was elected to Congress under the Articles of Confederation and was quickly elected as the presiding officer of the Confederation Congress. He served in that position during the end-of-war negotiations with Great Britain, during which, as president of the Congress, he signed the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War. After the war ended, Boudinot remained heavily involved in the young nation’s transition to peacetime independence.

Following this service in the U.S. Congress, Washington appointed him director of the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. After completing ten years in this role, Boudinot finally retired to Burlington, New Jersey.

Boudinot’s ancestors were devout French Huguenots, and Boudinot carried on this tradition of devotion. His Christian values led him to shun slavery. As the question was being debated in Congress, a few supporters of slavery tried to use the Bible to support their position. Boudinot responded with a sober warning. While God had preserved America thus far, He would not necessarily turn a blind eye to the sin of slavery forever:

It is true that the Egyptians held the Israelites in bondage for four hundred years, … but … gentlemen cannot forget the consequences that followed: they were delivered by a strong hand and stretched-out arm, and it ought to be remembered that the Almighty Power that accomplished their deliverance is the same yesterday, today, and forever.

Considering these words, it comes as no surprise that he gave complete credit to God for the success of the fledgling American nation as well. A letter from Boudinot in 1783 makes it clear that, in his mind, involving the Lord was the only way America could have survived its violent separation from England:

I have been in the midst of principal scenes of action during the whole contest. I have not been a bare spectator. I have carefully watched and compared the steps of Divine Providence thro’ the whole, and as the result, I can assure you that our success has not been the effect of either our numbers, power, wisdom, or art. It has been manifestly the effect (I was going to say the miraculous effect) of the astonishing interposition of a holy God in our favor. I do not mean in the least to derogate from the bravery, wisdom, patience, and perseverance of our army. … My meaning is that in no instance have our numbers, power, wisdom, or art been such that, in the judgment of impartial judges, success could have been reasonably depended on, independent of the overruling power of heaven. In many instances, our misfortunes have been our happiness, and often our blunders and mistakes have been the cause of our succeeding beyond the most sanguine expectations.

On another occasion, Boudinot lauded the Constitution and the new form of government that was being established while also expressing an earnest hope that the coming prosperity and newfound liberty of America would be preserved by the virtue and faith of the people:

Who knows but the country for which we have fought and bled may hereafter become a theatre of greater events than yet have been known to mankind? May these invigorating prospects lead us to the exercise of every virtue—religious, moral, and political.

Boudinot’s most important writing is a book penned in response to a later work of Thomas Paine’s. In 1776, Paine wrote his famous pamphlet, Common Sense, which took the American colonies by storm. It preceded the Declaration of Independence by six months and helped to solidify the colonists’ resolve to break free from Britain—and it cemented Thomas Paine’s status as one of the Revolution’s most memorable figures. John Adams himself noted, “[W]ithout the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.” He gave complete credit to God for the success of the fledgling American nation.

Adams records in his journal his conversation with Thomas Paine concerning his book, Common Sense. It is an early hint at Paine’s future work, The Age of Reason:

I told him further, that his reasoning from the Old Testament was ridiculous, and I could hardly think him sincere. At this, he laughed, and said he had taken his ideas in that part from Milton: and then expressed a contempt of the Old Testament and indeed of the Bible at large, which surprised me. He saw that I did not relish this, and soon check’d himself, with these words ‘However, I have some thoughts of publishing my thoughts on religion, but I believe it will be best to postpone it, to the latter part of life.’

He kept his word to John Adams and, beginning in 1794, Paine published a work that incited quite a bit of controversy. This work of Paine’s, entitled The Age of Reason, embraced many of the Enlightenment-era philosophies of the day, including deism, which some contemporaries condemned as atheistical. Boudinot’s priorities of faith, family, and virtue made him beloved.

In the dedication to his daughter, Susan, Boudinot explained:

I was much mortified to find the whole force of this man’s vain genius pointed at the youth of America. … This awful consequence created some alarm in my mind lest at any future day you, my beloved child, might take up this plausible address of infidelity. … I have endeavored to … show his extreme ignorance of the Divine Scriptures … not knowing that ‘they are the power of God unto salvation, to everyone that believeth.

While he is not as well remembered as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, or John Hancock, Elias Boudinot played a consistent and influential role in the founding of America. He was a model of the values held by the founders, who wished to see their nation prosper under God for many years to come and who lived their lives accordingly. Boudinot’s priorities of faith, family, and virtue made him beloved as a father, husband, friend, and statesman. And his writings, including The Age of Revelation, testify to his faith and the service he gave the citizens of this country. Thus, while the general public does not know him today, he undoubtedly left his mark upon countless contemporaries and most certainly upon America every Thanksgiving season.

Recognizing the importance of Boudinot’s work, The Age of Revelation, Mount Liberty Press, the publishing imprint of John Adams College, has issued a new, annotated edition of the work. In this way, the College honors Elias Boudinot and looks forward to a revival of appreciation for the man, his work, and the faith of a generation that brought about the United States of America. The Mount Liberty edition of The Age of Revelation is available on Amazon.

The post The First Thanksgiving Was for the Constitution appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →