Part one is found here; part two here.

When Christ prayed “thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven,” He was expressing a hope that the Kingdom of God could influence the world to reflect more of the goodness, justice, peace, and holiness of heaven. The “social gospel” can be understood as the way we apply gospel principles to improve the world around us, to make it more like heaven. Among Christians, Latter-day Saints have a unique approach to the social gospel since our principles are derived from a scriptural canon that includes, but also goes beyond the Bible. In addition, we have a unique church history that includes consecration and a communal economy called the United Order—along with a formal institutional welfare program in the present day, and courses on self-reliance, a humanitarian arm of the institutional church, and even a system to enable members to acquire university-level education at minimal cost. When we combine these resources with our congregation-level assistance and a community that provides support and opportunities for human connection, the Church presents a wonderful system for taking care of those in need and enabling upward mobility.

Similar to questions of belonging, when it comes to the social gospel, conservatives and liberals tend to diverge on questions of responsibility: How do we improve the world? By focusing like conservatives tend to do, on the flourishing of individuals and families? Or by focusing like liberals tend to do, on systems? The answer is yes. Systems are made up of individuals, so the quality of a system is only as great as the quality of the individuals that make up the system. Likewise, the systems in which we’re all embedded really do influence individuals and families in many ways.

Consequently, when conservatives try to improve society by making individuals and families better, their efforts can be limited or thwarted by systems that undermine individuals and families. Likewise, when liberals try to improve society by focusing only on systems, all of their efforts can be undermined very quickly by factors arising from disarray at the individual and family level. In the United States, for instance, we see that years of valuable systemic reforms are often wiped out in a single day by the executive orders of a single president, or by a few individuals that constitute a narrow legislative majority. And unstable families create disadvantages in people’s ability to benefit from any systemic progress. When we recognize no authority greater than our own thoughts and feelings, our religion is really just self-worship.

Uniquely Latter-day Saint Influences

The Bible has plenty to say about the importance in God’s eyes of ministering to the needy—which is an important imperative in the Church of Jesus Christ. In addition, Latter-day Saint views of the social gospel are uniquely influenced by restoration scripture: The Book of Mormon describes a communal Zion society where people shared all things in common and also contrasts that with descriptions of a stratified society with systemic injustice in the form of unequal chances to obtain education. King Benjamin echoed biblical prophets when he taught that even among devout believers, our standing before God is in jeopardy when we fail to attend to the most vulnerable in society:

And now, for the sake of these things which I have spoken unto you—that is, for the sake of retaining a remission of your sins from day to day, that ye may walk guiltless before God—I would that ye should impart of your substance to the poor, every man according to that which he hath, such as feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and administering to their relief, both spiritually and temporally, according to their wants.

Finally, the Doctrine and Covenants teaches the law of consecration, and also offers a glimpse into God’s egalitarian view of the ideal ordering of society: “But it is not given that one man should possess that which is above another, wherefore the world lieth in sin.”

No Justice Without Conversion

These scriptural views of social justice tend to resonate with liberal-leaning people more than they tend to resonate with conservatives, and they may even put liberals in a difficult bind. When liberals yearn for these concepts of social justice to be taught and promoted to a greater degree by church authorities, this yearning recognizes that there is value in treating scriptural texts and church leaders as authoritative. Further, if a believer were to recognize scriptural and prophetic authority in this instance but refuse to recognize it in other instances—say, in regards to the Family Proclamation—then his notion of authority is selective, and he views his own thoughts and feelings as the final arbiter of what is authoritative. It might be phrased as scripture and prophets are only authoritative when they agree with me. When we recognize no authority greater than our own thoughts and feelings, our religion is really just self-worship.

In Latter-day Saint church history, our failed attempts to implement the United Order (wherein some have subverted the collective good due to selfish interests) have shown us that to actually implement scriptural and prophetic teachings on social justice, everyone involved must consider those teachings as divinely authoritative, superseding our own thoughts and feelings.

The Book of Mormon’s account of an egalitarian Zion society contains an indispensable condition: conversion. The idyllic description of Zion is prefaced with “And it came to pass in the thirty and sixth year, the people were all converted unto the Lord, upon all the face of the land …” Conversion to Christ, holding to a common understanding of sacred history, and the commitment to give heed to a group of God’s ordained servants, were the cognitive and spiritual soil that enabled an egalitarian Zion society to emerge and thrive.

Conversion is an inner transformation and reorientation of the soul, different from simple commitment and zeal. The Zion vision of social justice is only possible among the authentically converted. Without the unifying power of real Christian conversion, attempts to imitate egalitarian Zion usually resort to winner-take-all politics or violent coercion to achieve their visions.

In recent years, political movements in the United States have become more sharply divided as to what constitutes social justice, or the ideal ordering of society. Both progressive and conservative politics are increasingly replacing faith among churchgoers who are bored or disillusioned with their religious traditions, and current and former presidents have come to be regarded as savior figures. For example, early in the Trump presidency, one liberal expressed her despair in the New York Times: President Obama, Where Are You? Later, in the 2020 campaign, Trump’s campaign manager would proclaim of his candidate “Only God could deliver such a savior to our nation …”

The 2020 election led Jeff Bennion and me to write a questionnaire for Latter-day Saints: Is Politics Your New Religion? Political movements of critical theory on the left and especially bizarre conspiracy theories on the right have increasingly come to resemble religion, with new prophets, saviors, confession, testimony-bearing, rituals, sacred texts, and more.

Cancel culture has taken hold in politics; it is normally thought of as a left-wing phenomenon, but as Ross Douthat recently noted, the shaming and career-derailing activities of cancel culture are found on the right as well—with examples of cancellation and silencing on college campuses attempted by both sides of the political spectrum as well. During the Trump presidency, many conservative commentators were shamed and shunned for showing less than total fealty to Donald Trump. As we have seen in canceling from the left, some people try to stop their cancellation with statements resembling forced confessions among people who are terrified for their personal safety and well-being, or as Sonia Sodha recently put it, “hostage notes”: abject apologies that speak to the ideas of people they fear. They employ quasi-religious language: my heart has been awakened to realities I was not able to perceive before. I now see the light and I apologize for my actions before I came to this new understanding. On the left, this kind of language is employed in confessions of white privilege and insensitivity toward the marginalized; on the right, it has been employed recently by politicians and commentators trying to get back into the good graces of Donald Trump. The Zion vision of social justice is only possible among the authentically converted.

I bring this discussion of cancel culture forward in an appeal to Latter-day Saints to recognize that it represents a fear-based counterfeit of unified Zion society—an overzealous sense of “this larger ideal we’re working towards is so important, that we need to coerce compliance with it.” Do we really think an approach so reliant on coercion and pressure can achieve the kind of society we want?

Clearly not. Any notion of social justice that relies on fear and grievance identities will never achieve God’s ordained vision for social justice, which balances a focus on systems with a focus on individual responsibility and commitment.

Concluding Thoughts

Rabbi Abraham Heschel once said:

It is customary to blame secular science and anti-religious philosophy for the eclipse of religion in modern society. It would be more honest to blame religion for its own defeats. Religion declined not because it was refuted, but because it became irrelevant, dull, oppressive, insipid. When faith is completely replaced by creed, worship by discipline, love by habit; when the crisis of today is ignored because of the splendor of the past; when faith becomes an heirloom rather than a living fountain; when religion speaks only in the name of authority rather than with the voice of compassion—its message becomes meaningless.

Heschel was correct, and this insight serves as a warning that extends to Latter-day Saints. We are just as prone to each of the problems Heschel describes. It would be a mistake, however, to assume that revitalizing our faith is a matter of abandoning our doctrines or watering down the miraculous story of the restoration to make it palatable to an unbelieving world. A better approach is to embrace orthodoxy, which allows both conservative and liberal instincts to operate together in the shared pursuit of God’s purposes.

Orthodoxy is a word that means correct thinking. Every belief system—including secular systems like science—has an orthodoxy, which is a way of thinking that allows the belief system to fulfill its promises. In the case of science, scientific orthodoxy is to experiment using the scientific method, leading to results that are objective and replicable. As Latter-day Saints, we have a belief system that from the early days of the restoration has offered connection to God, experience with the gifts of the spirit, continuous divine influence in the Church, a system of divinely-ordained leadership, and a loving, supportive community that can turn outward and spread God’s influence into the world. Latter-day Saint orthodoxy, then, is an approach to faith—sometimes conservative and sometimes liberal—that enables us to experience these promised fruits of our religion.

This is why it is so misguided to complain as church members sometimes do, that when church leadership promotes the traditional family or speaks emphatically about our doctrine, they are “being conservative.” Or that when they declare that Black Lives Matter or that we need to support care for refugees, they are “caving to liberal influences.” Years ago, President Dallin H. Oaks gave the orthodox perspective when he said, “Those who govern their thoughts and actions solely by the principles of liberalism or conservatism or intellectualism cannot be expected to agree with all of the teachings of the gospel of Jesus Christ. As for me, I find some wisdom in liberalism, some wisdom in conservatism, and much truth in intellectualism—but I find no salvation in any of them.”

This echoes CS Lewis’ teaching in Mere Christianity:

That is the devil getting at us. He always sends errors into the world in pairs—pairs of opposites. And he always encourages us to spend a lot of time thinking which is the worse. You see why, of course? He relies on your extra dislike of the one error to draw you gradually into the opposite one. But do not let us be fooled. We have to keep our eyes on the goal and go straight through between both errors. We have no other concern than that with either of them.

Jesus taught that “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” If our church leadership makes decisions that do not always neatly fit conservative or liberal expectations, that unpredictability is perhaps a sign of the influence of God’s spirit at work in the governance of the Church. When we are only ever willing to see the world through strictly conservative or liberal lenses, we are likewise partisans, not fully open to the influence of God’s spirit.

This is why in a presentation critiquing many conservative religious tendencies, Richard Rohr says “the liberal … he really isn’t going to be any better.” He goes on to underscore that the egocentric partisan mind is only secondarily seeking God and truth for their own sake. Even without realizing it, religious people in a partisan mindset will use religion primarily as a means to advance and defend their ideological team, rather than experience the healthy suffering and vulnerability that are part of real spiritual growth. Conversion asks how can I take in more of God’s loving truth and share it with the world? Partisan thinking asks how can I promote my team and signal to the world my team allegiance? Remarkably enough, this partisan impulse is a mirror image of itself on the left and right. Rohr explains:

This has been the failure of so much of liberalism: it has been trying to critique from the same mind … As long as you read reality from that small self, and read reality calculatively, I don’t think you’re going to see things in any new way. Maybe you’ll move along the political spectrum from left to right or right to left, but what all great religions have talked about is a different way of seeing.

Neophilia (love of new things) and neophobia (aversion to new things) that I discussed in part one are indicators of liberal and conservative tendencies. However, the restored gospel as found in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints speaks to both of these: bringing forth new ways of understanding God and our mortal life, as well as holding firmly to established doctrine that is grounded in witness testimony and other important sources of truth.

Here in this series, I have only covered a few areas of religion where conservative and liberal instincts differ. Many more areas could be discussed. What I hope is to avoid the trap so common in human nature, of insisting that our conservative or liberal tendencies are the only reasonable or right ones. Rather than elevating right or left-leaning impulses as the “one true path” to reaching greater happiness or well-being, I hope this exploration has encouraged pause—along with perhaps greater generosity toward what these different impulses can offer.

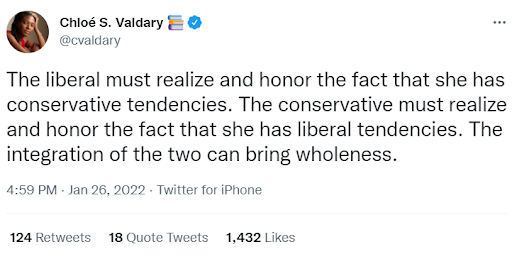

As Chloe Valdary recently said,

With more thoughtful attention to conservative and liberal approaches to faith, we can see strengths and weaknesses of each approach, depending on the situation. We can appreciate those differences and keep a mindful awareness of our own tendencies and strive to see the value in others’ differing ways of thinking. We can see other people’s instincts as gifts, and see our differences as room to grow.

To live with a mindful appreciation for the differing gifts of our conservative—and liberal-leaning church members would be another remarkable and unique example for Latter-day Saints to offer to the world.

The post Doing Good in Conservative and Liberal Religion appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →