Finances and Faith in the Kirtland Crisis of 1837

by Elizabeth Kuehn

(This is from a presentation given at the 2017 FairMormon Conference)

While I will cover nineteenth-century economics and the Kirtland bank briefly in my presentation today, I also want to focus on the period of spiritual crisis in Kirtland in 1837 and ways I hope we can learn from the Kirtland experience for our current moment of spiritual crisis.

The crisis within the Mormon community of Kirtland has been inseparably connected to the founding and subsequent failure of the church’s Kirtland bank. However, there is too often a direct causal connection assumed between the bank and the 1837 crisis. The focus of my presentation today is to demonstrate the complexity of this period of history, contextualize both the bank and the crisis, and address several prevailing assumptions about each.

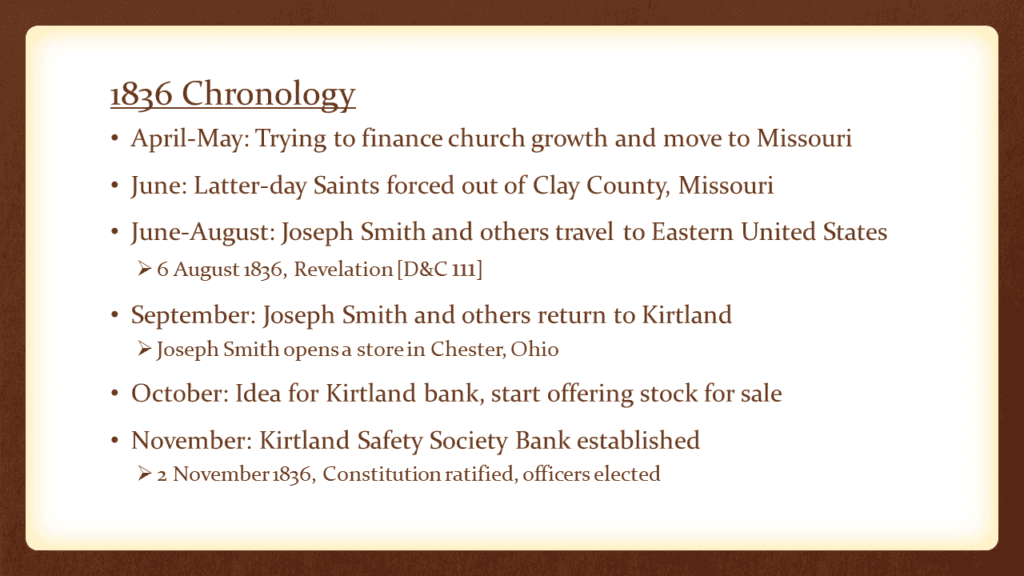

Although most Kirtland narratives place the bank amid the financial devastation of 1837, the Kirtland Safety Society Bank was organized in November 1836. As such, understanding developments in Kirtland in 1836 is key.

In 1836, Kirtland was a growing and thriving community, enjoying the same sense of economic success experienced throughout the United States. The Kirtland Temple, which the Latter-day Saints had sacrificed and worked for years to complete was dedicated at the end of March and accompanied by profound Pentecostal experiences. With the dedication of the Temple, Joseph Smith expanded his aim from building a House of the Lord to building up Kirtland as a city and stake of Zion. He encouraged church members to join him in this endeavor and to invest in their community. Despite this enthusiasm, church leaders faced difficult financial realities. Although church members had sacrificed a great deal for the Temple, much of the construction costs were borne by the church, namely the temple building committee, resulting in thousands of dollars of debts. Joseph Smith and other church leaders were aware of and concerned by the substantial debts amassed in building the Temple, but this was not the crippling debt it has sometimes been made out to be. Church leaders were worried, not desperate.

Another significant concern facing Joseph Smith and other church leaders in the summer of 1836 was the forced removal of the Latter-day Saints living in Clay County, Missouri. As tensions increased between the growing Latter-day Saint population and their Missouri neighbors, Missouri church leaders acquiesced to the demands of Clay County citizens and agreed to leave rather than face the mob violence they had experienced in Jackson County. With concerns about the Missouri Saints, the redemption of Zion, and financing church growth on his mind, Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Sidney Rigdon, and Oliver Cowdery left Kirtland for a trip to the Eastern United States in late July. While in Salem, Massachusetts Joseph received a revelation on August 6, 1836, now canonized in the LDS version of the Doctrine and Covenants as D&C 111. This revelation offered specific reassurance – that Zion would be redeemed and that the church would be able to repay its debts.

When Joseph Smith and his companions returned to Kirtland in mid-September 1836, they began making plans for several business ventures. Joseph in partnership with Sidney Rigdon, and possibly Oliver Cowdery, started a store in Chester, Ohio.[1] Joseph also bought a significant amount of land in the Kirtland area – over 400 acres.[2] Some of this land was likely intended for use by newly arrived church members, but a portion also likely served as security for the other significant business venture that Joseph Smith and several other Latter-day Saints started in the fall of 1836 – a bank.

The initial plans for the bank came together in October 1836 and on November 2nd, stockholders approved the bank’s constitution, and elected Sidney Rigdon and Joseph Smith as the bank’s officers.[3] The fact that the Society began in 1836 is sometimes overlooked in broad generalizations about Kirtland, but this context is critical to understanding the impetus for the bank. As I mentioned earlier, 1836 was a year of growth and seeming prosperity in Kirtland and the United States more generally. This period of prosperity led thousands of individuals to take financial risks, to speculate in land, cotton, or other markets; and to over-extend their credit under the assumption that such prosperity would continue and they would be able to repay what they had borrowed. While we often look back with hindsight and condemn the Kirtland Safety Society as a failure from its creation, the feeling among the Saints in 1836 was not impending failure but that of ambition and an assumption of continuing prosperity.

Additionally, a bank made sense for a growing community like Kirtland. Smaller frontier banks established by local members of the community were a common feature in nineteenth-century America. Banks allowed illiquid assets like land – the only real asset the Latter-day Saints had – to be used as collateral for loans, providing money the church and its members needed to buy land, build homes, and aid church members in Missouri.

There is the assumption that the bank was created in a desperate attempt to pay the debts of the church. While hoped for revenue from the bank was surely intended to aid the church, and pay off church debts, there is a tendency to overemphasize the debts of the Kirtland period. As if this was the only time Joseph Smith or the church was in debt. The money owed for the Kirtland temple was significant – and Joseph struggled to pay off these debts for the rest of his life – but, what we should keep in mind is that neither Joseph Smith nor the church were ever truly financially stable. Debt was a reality not only of trying to build communities with little resources, but also the difficult financial circumstances the Latter-day Saints faced in being driven from one community to the next and trying to aid impoverished members and new converts.

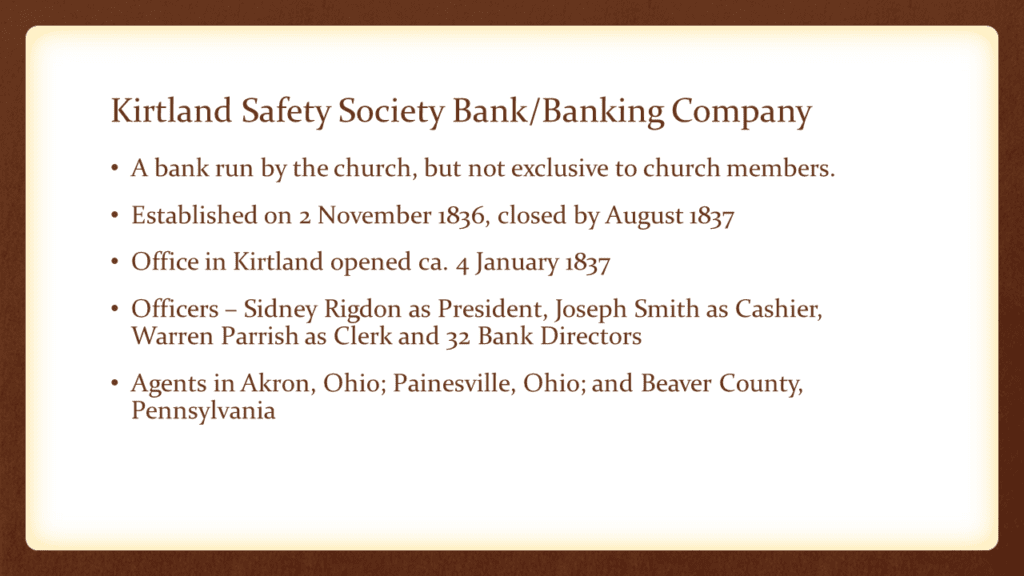

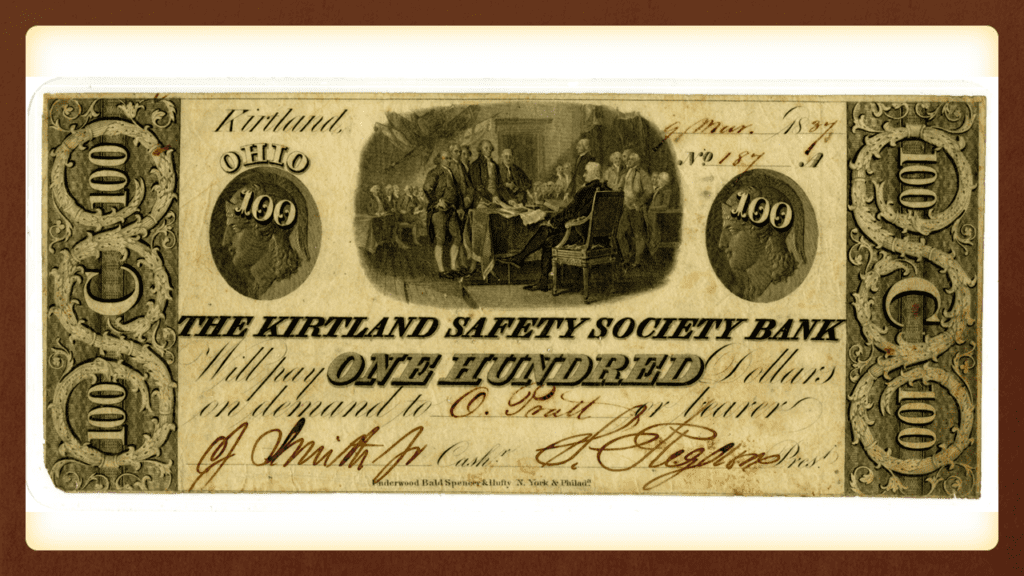

The Kirtland Safety Society Bank, later called a Banking Company, was a church run bank that was not exclusive to church members. While most stockholders were members of the church, a small number of residents in the area of northeastern Ohio were also involved in the bank. Although organized in the fall of 1836, the Society did not begin operating an office until early January 1837, after the institution had been restructured and was briefly given the cumbersome name of the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company.[4] Unable to acquire a charter and official incorporation from the Ohio state legislature, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon and others involved in the Kirtland Safety Society resolved in January to continue to function as a bank without legislative approval. This was a common extra-legal workaround used by many societies in Ohio, and rarely regulated or prosecuted. Unfortunately, the small-scale bank that the Safety Society was has no modern parallels, and is an oddity of early community banking. There are no records to suggest it was a deposit bank, meaning that the Kirtland Safety Society issued loans and exchanged its notes with the notes of other banks, but did not hold money for any individuals. The funds for the bank came not from deposits, but from stockholders investment in the bank.

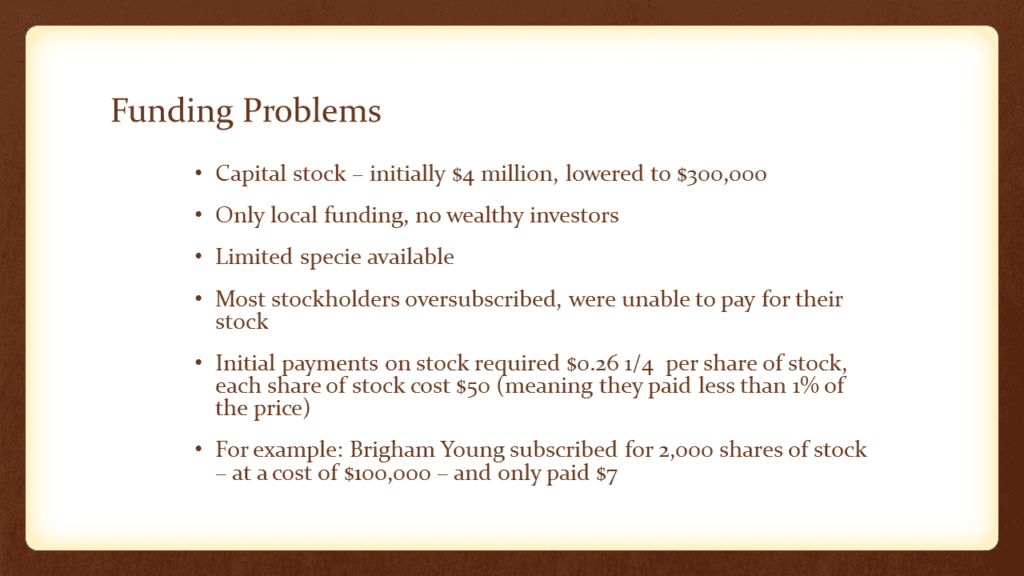

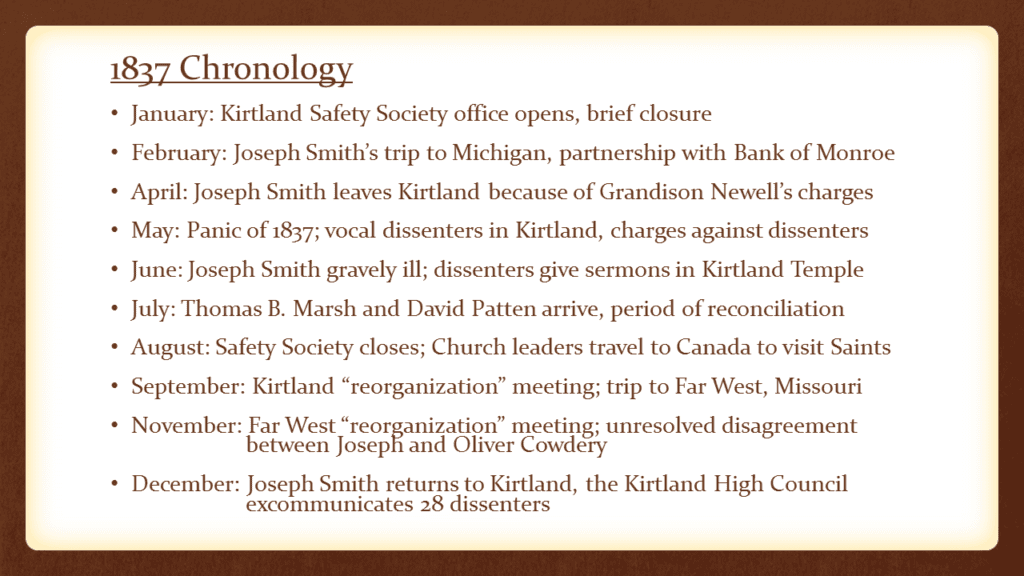

The Kirtland Safety Society was an ambitious endeavor and relatively short lived, closing by August 1837. The reasons it failed are many and complex, but no single factor caused the institution to fail. The lack of a charter and unclear financial backing coupled with religious prejudice led many to be skeptical of the bank’s credibility and solvency. Externally, the bank endured intense opposition from the press and from anti-Mormons in northeastern Ohio. Internally, only a little over 200 individuals invested in the bank as stockholders, even though the Mormon population in Kirtland was around 1,800 in 1837.[5] The financial structure of the bank itself was also extremely problematic. The initial capital stock, or required funding to operate, for the Kirtland Safety Society was impossibly high, at 4 million dollars.[6] This was significantly higher than other frontier community banks, whose capital stock averaged from $100,000 to $300,000. Most frontier banks relied on eastern investors to raise sufficient capital, and with the limited resources available in Kirtland and no wealthy investors, such an amount was out of the reach of the Kirtland Saints. Related to this structural problem was the financing for the bank. Funding was provided primarily by stockholders who purchased stock by subscription and then were required to pay for their stock in installment payments to the bank. Many of those who subscribed for stock did not pay even the first installment payment they owed, and those individuals that did pay the first installment usually did not make any additional payments.[7] When this funding fell short, Joseph supplemented it with short term loans from other Ohio banks.[8] Funding was also hampered by mismanagement, although not well documented, Warren Parrish was accused of embezzlement and counterfeiting.

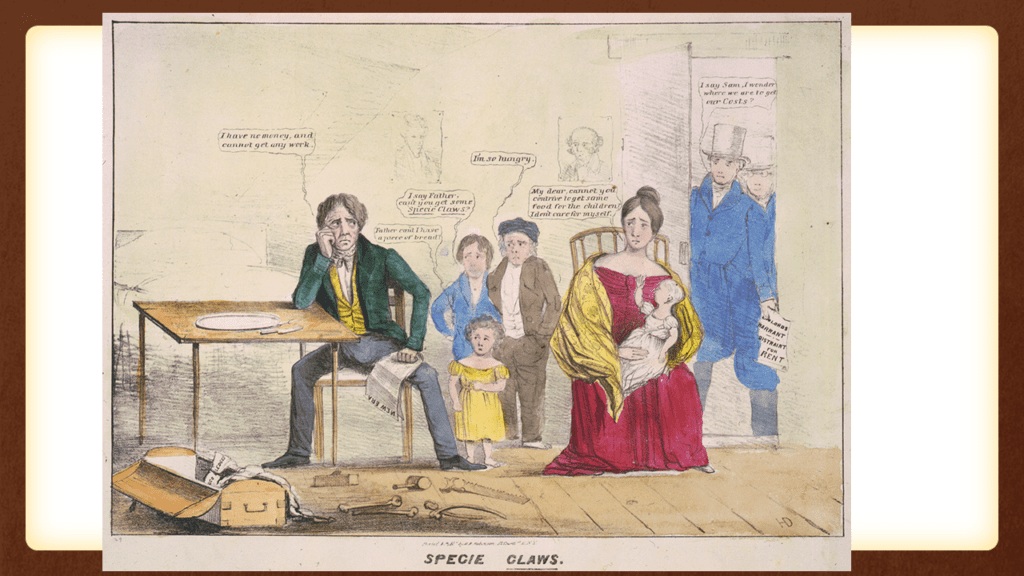

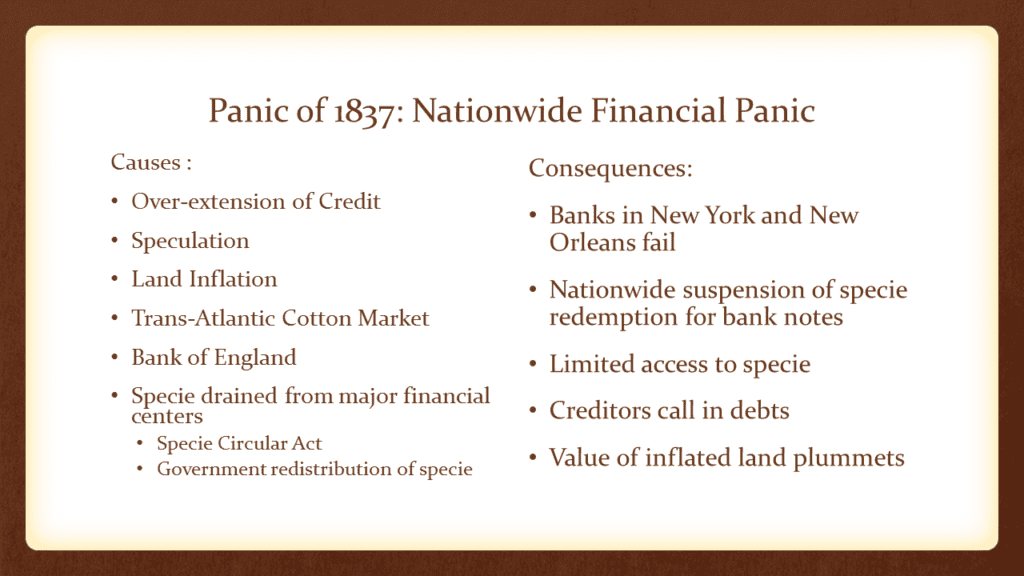

Ultimately, the bank failed because of the economic upheaval created by the nationwide financial panic – called the Panic of 1837 – that resulted in banks across the nation failing, land values falling, and debts being called in. The Panic of 1837 caused an economic decline that would lead to years of economic depression in the United States. This panic and resulting depression were catastrophic and are analogous to the Great Depression of the twentieth century. It was this financial panic that devastated the Kirtland economy, and not the failure of the bank. While many in Kirtland experienced some financial loss as a result of the bank’s failure, the community’s economy and individual church members’ finances were far more drastically affected by plummeting land values. Although many detractors then and now have held Joseph Smith personally responsible for the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society and downturn of the Kirtland economy, these were complex events for which Joseph was not individually responsible.

The economic downturn that followed the financial panic in May 1837 dramatically affected the Latter-day Saints in Kirtland. Warren Cowdery, who would distance himself from the church by the end of 1837, reflected in a July 1837 newspaper editorial that it would have been impossible for such a financial calamity not to have affected the Kirtland Saints.[9] Yet, often when we discuss Kirtland and the crisis of 1837, we overlook the financial realities of the Kirtland community, and omit the fact that their livelihoods, homes, and their ability to feed their families were at stake. Lessons on this topic simplify these nineteenth-century church members doubts and disaffection as apostasy, with no explanation of their concerns or of the gravity of their choices.

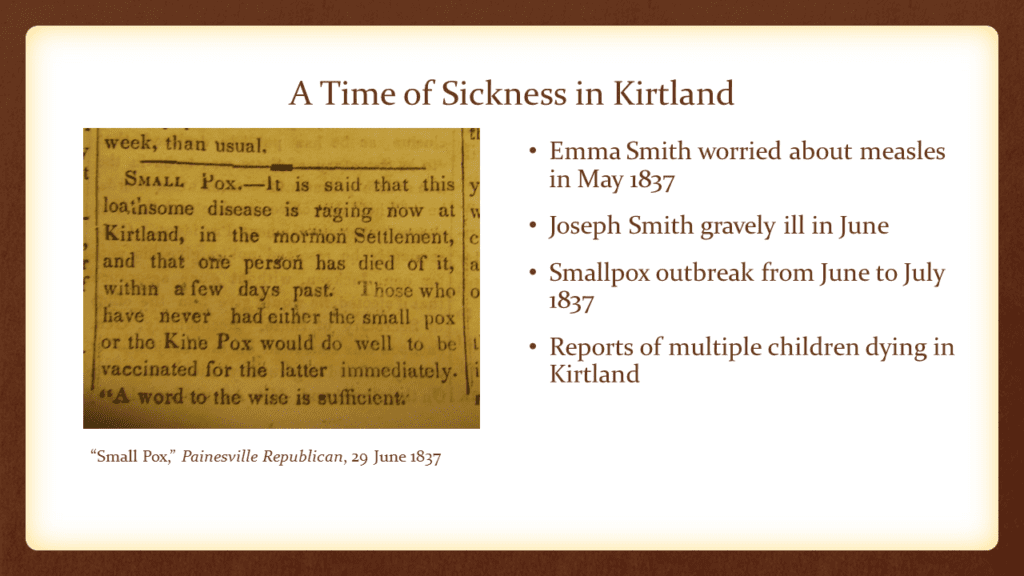

In addition to this financial devastation, a smallpox epidemic raged in Kirtland through June and July of 1837, and claimed the lives of several children.[10] Writing to Elias Smith, his family reported that “it is a very sickly time with children and quite a number of deaths have taken place within a few weeks past, yesterday there was two funerals attended at once in the meeting house both children and there is quite a number sick now.”[11] Writing in late July 1837, John Smith reported that “the small pox has Subsided but the Distroyer is yet among us in various forms, I have spent much of my time for a few Days past in Visiting the Sick.”[12] Joseph himself was gravely ill at this time, although his illness was not identified, and he could barely sign the recommendation given to Heber C. Kimball as he set out on the church’s first mission to England. Dissenters made the most of Joseph’s illness preaching their frustrations to the church. Mary Fielding, writing in June 1837 of a Sunday worship service where several disaffected members spoke – including Apostle Parley P. Pratt – noted that “the large congregation of Saints and Sinners had listened with great attention, some pleased but many greatly displeased.”[13]

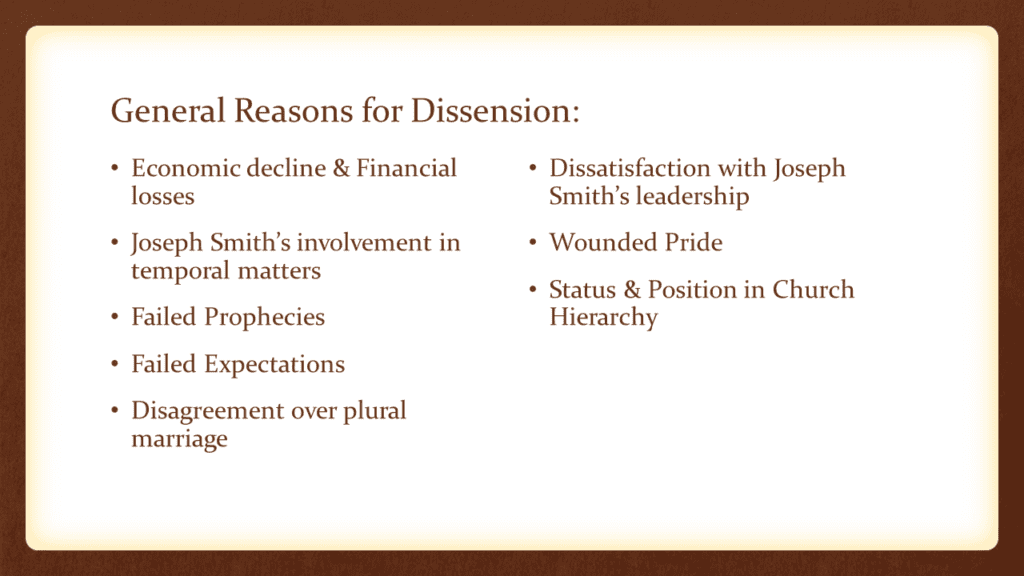

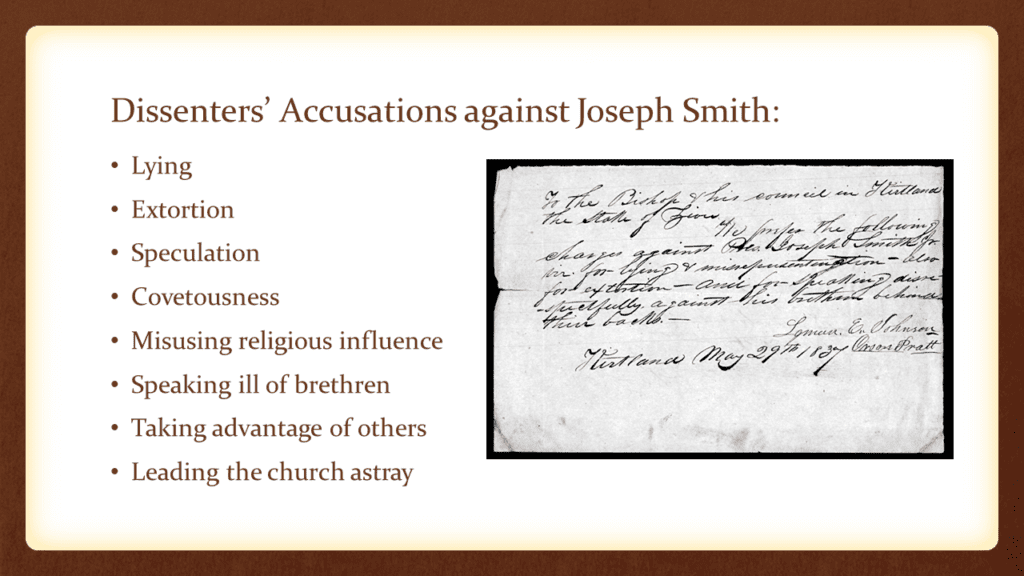

Although the bank did not on its own bring financial ruin, it does appear to have acted as a catalyst for doubts and dissatisfaction with Joseph Smith. Apostles Parley P. Pratt and John F. Boynton directed their anger and sense of betrayal specifically at the bank. Pratt faced the threat of losing his land and home because of economic difficulties and lashed out at Joseph Smith in a May 1837 letter, accusing him of speculation and lying. Boynton argued that he had lost his testimony of Joseph Smith as a prophet because the bank which he believed had been founded by revelation had failed. The fault here is less the bank and more doubts about Joseph Smith’s prophecies and leadership of the church. Many of the members who became dissenters in the summer of 1837 felt they had been misled, or even betrayed. Joseph Smith had promised them financial success if they would invest their resources and help him build the city of Kirtland. In April 1837, he had described Kirtland as a grand and expansive city that would be a center of commerce, where the “Kings of the earth would come to behold the glory thereof.”[14] However, as a result of the Panic of 1837, the Saints were left with failed businesses, unsaleable land, and an inability to provide for their families. The core of the dissenters’ betrayal was not solely the bank, but that a man they believed to be a prophet had not warned them of impending financial danger and that the church’s banking company had brought financial loss not success. This was financial failure, but it was also a failed prophecy of prosperity. And for some this called to mind earlier failures and frustrations, such as those experienced by the Camp of Israel in 1834.[15]

Another part of this perceived failure, was Joseph Smith’s failure as a temporal leader as well as a prophet. Some dissenters felt he had overreached by directing the Saints in temporal matters. Joseph Coe opposed the prophet’s involvement in and control over temporal matters, arguing that it went beyond the purview of his spiritual leadership and there were others who could better direct such matters.[16] Oliver Cowdery argued that Joseph should not be able to dictate what he did with land he owned. Warren Cowdery, Oliver’s brother, called Smith a tyrant. Many dissenters seemed to chafe under the idea of Joseph leading in both spiritual and temporal matters as well as the degree of control he exercised over the church and its members. Still others reacted out of wounded pride, feeling that they were not given the positions in church leadership they deserved.

Facing financially devastation and individual doubts, for many Saints the Prophet had not lived up to their expectations. Expectations which seem to have required perfection and omniscience of a prophet. With the reality of Joseph Smith’s imperfection and the possibility that not every church venture would succeed, several stumbled. Some, like Boynton, said they had lost their faith. A few, like Warren Parrish, became fierce opponents, actively working to discredit and malign Smith. Others were able to reconcile the apparent imperfections and chose to continue to follow Joseph Smith. And on this spectrum of reactions, many church members probably fell in the space in-between complete acceptance or rejection. How far the dissent existed beyond the few individuals named in contemporary records is difficult to capture. Heber C. Kimball, who had left Kirtland on a mission to England in July 1837 would hyperbolically suggest that Joseph Smith did not have a single supporter in Kirtland. Similarly, in an 1837 letter to her husband, Phebe Woodruff warned that she had been told that thousands shared the sentiments of the dissenters.[17] Writing in January 1838, Vilate Kimball felt that some who had been persuaded to join Warren Parrish and the excommunicated dissenters would have a change of heart and soon return to the Latter-day Saints and expressed her own and others loyalty to the Prophet.[18] It is clear that the doubts and dissatisfaction expressed by the apostles was also experienced by church members more broadly, but the extent of these feelings among the Kirtland Saints is impossible to accurately measure with the extant records.

However, the sense of betrayal cut multiple ways. While the dissenters had legitimate reasons for feeling betrayed, so too did Joseph Smith. He had worked to build a place of safety and strength for the Saints and he was met with disunity, financial failure, and close friends denouncing him as a false prophet. Joseph took four lengthy trips in 1837 – in February, April, August, and October – and with each trip dissent escalated during his absence. Dissension, division, and disunity were a constant reality for the Kirtland community throughout 1837 and into 1838. There were moments when opposition peaked, and others when it seemed to quell for a time, but it never entirely dissipated. This tension took a heavy emotional toll on Smith and the entire church. The religious community that had been united in completing, and dedicating a Temple in March of 1836 was deeply divided by January 1838.

At its core, the Kirtland crisis of 1837 was what we might term today a faith crisis. Decades later in Utah, Joseph Young in reflecting on the bank would call it a stumbling block for the Saints[19] – a point at which they had to decide if they believed that Joseph Smith was indeed a prophet, and whether they could follow a prophet who would not always succeed, who would make mistakes, and who might require financial loss, failure and suffering in order to achieve the requirements of God.

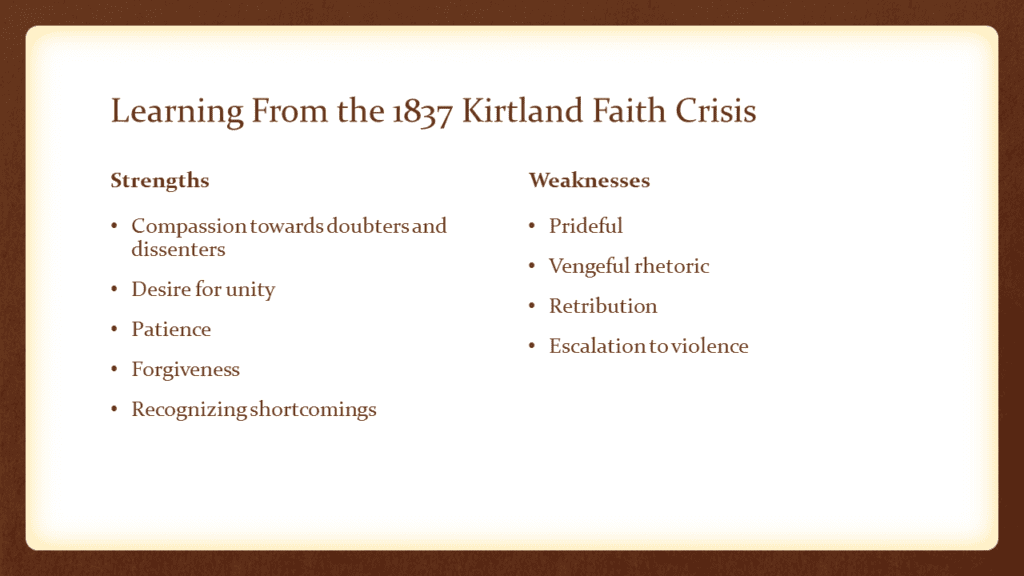

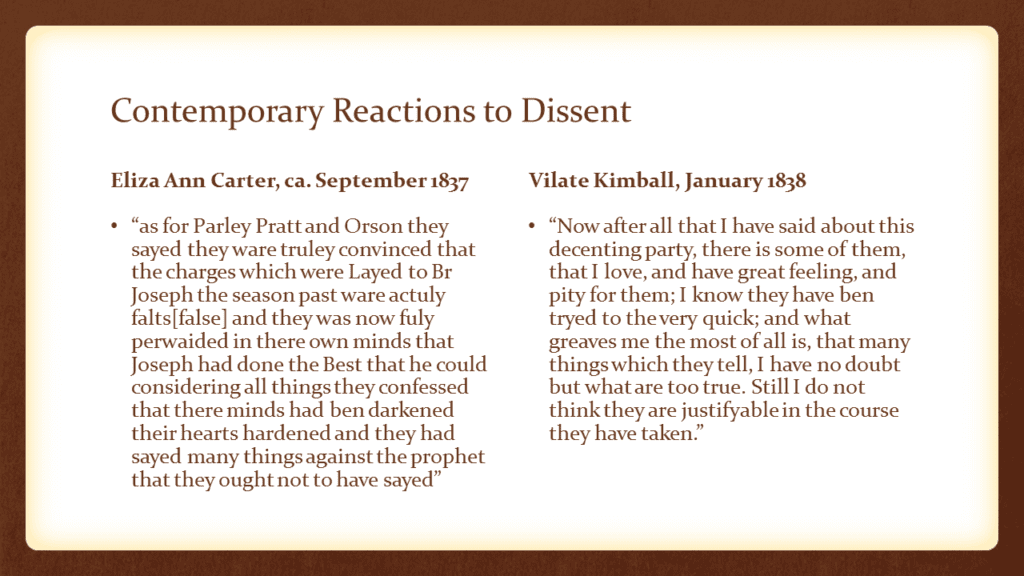

In our current climate of uncertainty, as many members and former members struggle with their own personal crises of faith, there is much we can learn from the way the Kirtland Saints reacted to the doubt and division in their community. Several reacted with compassion and understanding, recognizing the frustration and hurt experienced by those doubting or opposing Joseph Smith. In a January 1838 letter, Vilate Kimball conveyed her distress about the excommunicated dissenters: “Now after all that I have said about this decenting party, there is some of them, that I love, and have great feeling, and pity for them; I know they have ben tryed to the very quick; and what greaves me the most of all is, that many things which they tell, I have no doubt but what are too true. Still I do not think they are justifyable in the course they have taken.”[20] In her correspondence, Mary Fielding emphasized her desire for unity and that peace would be restored to the divided community. Each of these women recognized the emotional toll this division had on the community, writing about their anxiety and the concerns of leaders trying to encourage the Saints to be more humble. In one letter, Mary related a sermon by Hyrum Smith where he exhorted the Saints to be more Christlike and “he asked us if we did not then feel as humble as little Children he assured us that he for one did, and observed I think my heart is soft and I now feel as a little Child.” She recounts that at this point “he was then affected to tears and could not proceed but had to sit down for a short time to give vent to his feelings after which he again arose and begged the congregation to excuse his weakness before he concluded, he seemd to be filld with t[he] spirit and power of God.”[21]

Although Joseph would later reflect bitterly on the actions of the dissenters, in the summer of 1837 he appears to have been patient, not reactionary, toward those who opposed him. The most outspoken dissenters came forward in late May and early June, but it was not until September that a church conference was called and dissenters were removed from positions in church leadership.[22] While this delay may have partially been the result of his illness over the summer and trip to Canada in August 1837, it also gave the dissenters time to consider their positions, to meet with him, and express their concerns. Even in September, no dissenting individuals were excommunicated. With the mediation of Thomas B. Marsh, most of the dissenting apostles had compromised and agreed to once again follow Joseph Smith.[23] At this news, Vilate Kimball rejoiced and wrote that she thought in that moment, she “could realize some of the feelings of the Prodigal, when his rebelous son returned home.”[24] Part of this reconciliation appears to have been Joseph recognizing his own shortcomings. A recently discovered letter written by Eliza Ann Carter in 1837 suggests that just like the dissenting apostles were required to give public confessions before the Saints, Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon also publicly confessed that they had erred in this difficult time.[25]

Of course, for many of the dissenters their reconciliation turned out to be temporary and by December the dissenters’ intensity and persistence resulted in the Kirtland High Council excommunicating 28.[26] Just as the dissenters had been unable to let their grievances go, so to the reactions of those who stayed in the church were imperfect. John Smith noted in January 1838 that the church was better off for having removed the dissenters, writing that the church had “taken a mighty pruning and we think She will rise in the greatness of her strength.”[27] Unfortunately, tensions escalated to threats of violence. Hepzibah Richards wrote her brother, Willard Richards, that their cousin, Brigham Young, had been forced to leave Kirtland because the dissenters threatened his life, and that the lives of the First Presidency were also threatened.[28] The evening of January 15, 1838 the church’s recently auctioned printing office was destroyed by arson. Deep fissures existed between excommunicated dissenters and Latter-day Saints, and Kirtland continued to be a divided community for years after the majority of Latter-day Saints had relocated.

The Kirtland crisis of 1837 was complex and emotional. Too often this period is simplified, written off as a moment of confusion and depicted by darkness. One of the films at the Kirtland Visitor Center summarizes the entirety of this time of temporal and spiritual crisis with a phrase along the lines of: “And then things got hard…” Times were indeed hard, the Kirtland economy was devastated, and the Mormon community was in turmoil. But this complexity adds depth and gravity to a misunderstood time period.

Although establishing a bank may seem like an odd or reckless choice, it made sense for the period and for the Kirtland community. The situation that led to the bank’s failure was complicated, Joseph Smith was neither solely to blame nor innocent in its demise. The economic conditions in 1837 made it impossible for the bank to continue, but there were inherent problems and significant opposition from its founding. The same climate of economic disaster led some Latter-day Saints to reassess their expectations of the Joseph Smith as a prophet and question his leadership and decisions. While many were concerned with finances, the reasons for their opposition to Smith were distinct and personal, and for some represented longstanding concerns. Some dissenters, like Parley and Orson Pratt relented and were willing to once again follow Joseph, others distanced themselves from the church either voluntarily or through excommunication. But despite their momentary anger and bitterness several former members maintained or later revived friendships with Latter-day Saints. These relationships would lead them to reconnect with the church in Nauvoo, not out of a desire to rejoin the faith but out of friendship that transcended religious differences and past disagreements.

More Come, Follow Me resources here.

Endnotes

[1] For more information on the store in Chester Ohio, see “Notes Recieveable from Chester Store, 22 May 1837,” in Brent M. Rogers, Elizabeth A. Kuehn, Christian K. Heimburger, Max H Parkin, Alexander L. Baugh, and Steven C. Harper, eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, “Documents, Vol. 5: October 1835- January 1838 (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2017), 382-385.

[2] For more information on Joseph Smith’s Kirtland land purchases see “Mortgage to Peter French, 5 October 1836,” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 293-299.

[3] “Constitution of the Kirtland Safety Society Bank, 2 November 1836,” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 299-306.

[4] “Articles of Agreement for the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company, 2 January 1837,” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 324-331.

[5] Milton V. Backman, The Heavens Resound: A History of the Latter-day Saints in Ohio, 1830-1838 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1983), 140.

[6] “Constitution of the Kirtland Safety Society Bank, 2 November 1836,” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 299-306.

[7] Introduction to Part 5, in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 289-290.

[8] Joseph Smith took out short term loans at the Bank of Geauga and Commercial Bank of Lake Erie. (Introduction to Part 5, in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 290.)

[9] Warren Cowdery, Editorial, LDS Messenger and Advocate, July 1837, 3: 520-521.

[10] “Small Pox,” Painesville Republican (Painesville, Ohio), Jun 29, 1837.

[11] Julia and Mary Jane Smith to Elias Smith, Aug. 1837, Elias Smith Correspondence, CHL.

[12] John Smith to George A. Smith, 28 Jul. 1837, George Albert Smith Papers, CHL.

[13] Mary Fielding to Mercy Fielding Thompson, ca. Jun. 1837, Mary Fielding Smith Collection, CHL.

[14] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, 9 Apr. 1837, Wilford Woodruff Journals and Papers, CHL.

[15] For more information regarding accusations brought against Joseph Smith in relation to the Camp of Israel expedition, see “Minutes, 28-29 August 1834,” in Matthew C. Godfrey, Brenden W. Rensink, Alex D. Smith, Max H Parkin, and Alexander L. Baugh, eds. The Joseph Smith Papers, “Documents, Vol. 4: April 1834- October 1835 (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 120-135.

[16] Mark Lyman Staker, Appendix: George A. Smith, Sermon, 13 Nov. 1864, in Hearken O Ye People: The Historical Setting for Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2009), 571-572.

[17] Phebe Woodruff to Wilford Woodruff, 1 March 1838, Wilford Woodruff Collection, 1831-1905, CHL.

[18] Vilate Kimball to Heber C. Kimball, 19 Jan. 1838, Heber C. Kimball Collection, CHL.

[19] Joseph Young to Lewis Harvey, 16-18 Nov. 1880, CHL.

[20] Vilate Kimball to Heber C. Kimball, 19 Jan. 1838, Heber C. Kimball Collection, CHL.

[21] Mary Fielding to Mercy Fielding Thompson, 7 Oct, 1837, Mary Fielding Smith Collection, CHL.

[22] “Minutes, 3 September 1837,” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 420-425.

[23] “Revelation, 23 Jult 1837 [ D&C 112],” in Rogers et al., Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, 5, 410-414.

[24] Vilate Kimball to Heber C. Kimball, ca. 10 Sept. 1837, Heber C. Kimball Collection, CHL.

[25] Eliza Ann Carter to James C. Snow, 22 Jul. 1837; for text of letter see Reid N. Moon, “Jane Austen Meets the Wild West: Letter From a Young Woman in Kirtland,” Apr. 25, 2017, Meridian Magazine < http://ldsmag.com/jane-austen-meets-the-wild-west-letter-from-a-young-woman-in-kirtland/>

[26] John and Clarissa Smith to George A. Smith, 1 Jan. 1838, George Albert Smith Papers, CHL.

[27] John Smith to George A. Smith, 15-17 Jan. 1838, George Albert Smith Papers, CHL.

[28] Hepzibah Richards to Willard Richards, 18-19 Jan. 1838, Willard Richards Journals and Papers, CHL.

Elizabeth Kuehn received her Bachelor of Arts in History from Arizona State University and her Masters of Arts from Purdue University in History, with a focus on religious history and women and gender studies in early modern European history. She entered a doctoral program in History at the University of California, Irvine, and became a PhD candidate there in 2011.

Elizabeth Kuehn received her Bachelor of Arts in History from Arizona State University and her Masters of Arts from Purdue University in History, with a focus on religious history and women and gender studies in early modern European history. She entered a doctoral program in History at the University of California, Irvine, and became a PhD candidate there in 2011.

Since 2013, she has worked as a documentary editor and historian on the Joseph Smith Papers Project based at the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah. She is a co-editor of several documentary editions of the Joseph Smith Papers, including Documents Volume 5: October 1835-January 1838; Documents Volume 6: February 1838 – August 1839; and Documents Volume 10: May to August 1842, which was published in May 2020. She is currently the lead editor of the Financial Records series of the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

Her research interests include the Latter-day Saint communities in Kirtland, Ohio and Nauvoo, Illinois; the financial records of Joseph Smith; and Nauvoo era plural marriage. She has worked to bring greater inclusion of women and representation of their experiences to the Joseph Smith Papers Project.

The post Come, Follow Me Week 41 – Doctrine and Covenants 111-114 appeared first on FAIR.

Continue reading at the original source →