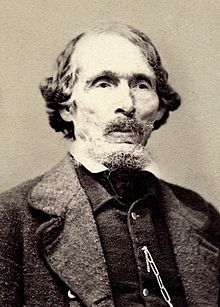

WW Phelps, who penned “Praise To The Man” that includes the phrase “Sacrifice brings forth the blessings of heaven”.

Since last night we commemorated the atonement, and today the crucifixion of Jesus Christ, I’ve been thinking about sacrfice. In conversation, a man not of our faith commented pretty much everything Mormons consider a “sacrifice” is offered only in exchange for something better. “It’s like you use your agency to barter for better returns from your God. But true sacrifice is only given when made with no expectation of blessings in return”.

His words have given me pause. Since sacrifice is supposed to be a central part of every saint’s life, and since we are indeed under covenant to render sacrifice to the Lord, what, then, does sacrifice look like? If obedience to God’s commandments is less a sacrifice than an exercise in enlightened self-interest, where does our sacrifice occur? And why do we sacrifice?

I think sacrifice is a key element in sanctifying our souls. We render sacrifice by giving up something to God. Loss seems to be the basic element of sacrifice, and there are different kinds: general, universal sacrifices tied to promised blessings (e.g., tithing), and losses that are more lasting, individual and unique (e.g. abuse, financial misfortune, health issues, family problems). These losses don’t feel like they bring any blessings in their wake. They’re just hard things.

But perhaps these hard things are our opportunities for sacrifice?

The difference between the two kinds of loss comes down to a question of consent. We choose to pay tithing or keep commandments, but we have little choice in some of the other losses in our lives. No one asks beforehand if we want to suffer physical, family, professional or financial hardships.

So our attitude toward these more particular, often more difficult or permanent losses, seems to be what determines whether our hardships are made holy, or if they simply remain hardships.

We aren’t asked to consent before the fact to these losses, but we can consent after the fact, and when we do so, we can transform those losses into sacrifice.

When we humbly continue to love God, like Job did despite being stripped of health, wealth, love and success, our sacrifice becomes akin to Abraham’s, when he laid Isaac upon the alter, even though it surely seemed illogical and pointless.

The more illogical the sacrifice is, the more meaningful it can become. Faith does not really enter into the decision to abstain from ingesting poison. People who don’t eat poison aren’t being faithful; they’re just being reasonable. Hence, I may not understand the rationale or agree with a given commandment, but in choosing to conform my will to His, it can become a genuine sacrifice.

If we are commanded to avoid one fruit (seemingly) arbitrarily selected from among a bunch of other fruits, (or to not drink coffee and tea, get multiple piercings or tattoos, or keep the law of chastity, engage in various activities on the sabbath, etc.) then my choice to avoid that forbidden fruit can come from no other source than my commitment to obeying God’s will. Faith only becomes a factor when the intellect is made inoperative–when the command seems petty, nonsensical, or completely random.

Thus when we give our consent to the “losses” that make the least sense, then we are sincerely sacrificial. That’s when we are truly saying “thy will be done” (even if we’re saying it with soul-rending sobs), and our losses can be consecrated and counted as good, and lead to the sanctification of our souls.

Have you ever turned a loss into a sacrifice? What are your thoughts on why we make sacrifices? How does sacrificing change you?

Continue reading at the original source →