Download Print-Friendly Version

Download Print-Friendly Version

The antichrist is a figure in scripture who has loomed ominously in the minds of Christians through the ages. He has been the subject of scary Hollywood movies and countless commentaries. Believers have speculated as to his identity and attached the title of antichrist to political leaders and even popes. Sermons on the antichrist have spread nervousness and dread through Christian congregations, and world events have been seen as bringing about the fulfillment of prophecies of his arrival.

The primary sources for most Christian understanding of the antichrist are Paul’s writings and the book of Revelation. Writing to the saints at Thessalonica, Paul warned of a time when

…that man of sin be revealed, the son of perdition;

Who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped; so that he as God sitteth in the temple of God, shewing himself that he is God.

This mysterious figure is described as a man of sin, taking to himself the honors and reverence that people normally give to God. Paul adds,

Even him, whose coming is after the working of Satan with all power and signs and lying wonders,

And with all deceivableness of unrighteousness in them that perish; because they received not the love of the truth, that they might be saved.

And for this cause God shall send them strong delusion, that they should believe a lie:

That they all might be damned who believed not the truth, but had pleasure in unrighteousness.

With this second description, the focus is on his—and our—relationship with the truth. Paul makes a distinction between those who love the truth and those who are perishing because they don’t. In the case of the antichrist, the people desire delusion. God will give them delusion, and ideally, they will learn (the hard way) from the experience and develop different desires.

The peril of conspiracy thinking

This desire for delusion can take many forms, particularly with complex issues that don’t have obvious culprits or a clear solution. One ominous trend on the horizon is the increase in conspiracy thinking. A notable example in recent memory was during hurricane Helene, which hit the Eastern U.S. during the 2024 presidential election. After Helene hit North Carolina, there was a flood of social media posts asserting that some evil group had created or steered the hurricane for nefarious reasons. One of the posts on X said the following:

Others followed a similar line. Posts such as these demonstrate the appeal of conspiracy thinking: they seek to make the world’s difficulties explainable rather than leave us with the pain and frustration of knowing that sometimes bad things just happen, and some people just do evil things without any hidden “puppet masters” controlling their choices. The challenge for truth-seekers is to avoid being seduced into thinking we are “the enlightened ones.”

Latter-day Saints know that from the early days of the restoration, conspiracy theorists have sought to undermine the Church by creating narratives of conspiracy involving Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other prophets and valiant saints. In the present day, conspiracy thinking is the source of a significant amount of the accusatory behavior toward our current Church leadership. For centuries now, numerous conspiracy theories have been created in attempts to explain the Book of Mormon, and in broader Christianity, conspiracy theories have been created to argue that the resurrection of Jesus was a fraud.

For all of these reasons, when we read in the Book of Mormon about secret combinations, that is not a reason to turn off our critical thinking skills and believe anyone who claims to know about a conspiracy. We should understand that often the secret combinations to beware of are conspiracy theorists themselves. It is good to acknowledge real conspiracies that exist, but an appetite for conspiracy thinking that reflexively grants credence to those who claim to “see through” the “lies” is dangerous. We become vulnerable to deception because there are powerful incentives in money, fame, and recognition, for people to create false conspiracy theories that flatter their readers and viewers, leave them with delusional narratives of how the world works, and create predictable heroes and villains for every situation. As Arthur Brooks says in another context, “As satisfying as it can feel to hear that your foes are irredeemable, stupid and deviant, remember: When you find yourself hating something, someone is making money or winning elections or getting more famous and powerful.”

Attribution theory

In psychology, attribution theory seeks to explain how people assign causes for things. A simple example of this is gas prices in the United States. When gas prices go up, Americans with intense politically partisan worldviews generally respond in one of two ways: if they voted for the current president, they will attribute the rise in gas prices to some decision made by a past president whom they disliked, which decision is now negatively impacting consumers at the gas pump. If they voted against the current president, then they will claim that the current president’s decisions are causing high gas prices.

In both decisions, the partisan brain is not really interested in what is true. The partisan brain wants to feel politically validated, so partisans will first decide who deserves blame or praise and then engage in whatever motivated reasoning is necessary to support that conclusion. In a partisan mindset, we use all our powers of reason to attribute all good news to people we like and attribute all bad news to people we don’t like. Whether a narrative is actually true is a secondary consideration or just unimportant.

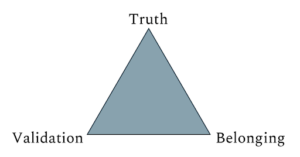

What motivates us

With all of the voices offering us narratives of current events, how do we avoid being deceived? A good thing to acknowledge is that none of us will be perfect in our truth-seeking. We should understand that even doing our best, all of us will always hold some amount of correct and incorrect views, and there is no shame in that. It’s part of the human condition. But we can strive to maintain self-awareness about what motivates us. When we turn on the TV or go online to find news and commentary, what are we really seeking? Below is a triangle of motivations to help with this process of self-awareness:

Starting with the lower motivations, we consider validation. To feel validated is a wonderful feeling, but it can become intoxicating and addictive. In his book The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt detailed how an experiment measured brain activity in people who were receiving politically validating messaging:

All animal brains are designed to create flashes of pleasure when the animal does something important for its survival, and small pulses of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the ventral striatum (and a few other places) are where these good feelings are manufactured. Heroin and cocaine are addictive because they artificially trigger this dopamine response. Rats who can press a button to deliver electrical stimulation to their reward centers will continue pressing until they collapse from starvation.

Haidt noted that in the experiment, as people transitioned from negative to positive messaging about their candidates, their brains created a reward of dopamine. He continued,

And if this is true, then it would explain why extreme partisans are so stubborn, closed-minded, and committed to beliefs that often seem bizarre or paranoid. Like rats that cannot stop pressing a button, partisans may be simply unable to stop believing weird things. The partisan brain has been reinforced so many times for performing mental contortions that free it from unwanted beliefs. Extreme partisanship may be literally addictive.

When we develop a strong enough appetite for validation, we become averse to any information that feels invalidating, including challenging truths that are needed for our personal development. Emotional and intellectual maturity involves learning to integrate new truths that challenge us.

Next, belonging is another important motivator. Latter-day Saints recognize the common process of growing up in a faith and holding beliefs in our youth out of a sense of belonging but then moving into stages of life where belonging is no longer sufficient grounds for our beliefs. We ask ourselves what we really believe, and why. This is a normal part of a person’s faith development. Similarly, many people grow up in families or communities with strong political orientations, but there comes a point where belonging is no longer a strong enough motive for their political loyalty. It feels good to have a team and to feel supported. But there are times when we feel compelled to ask ourselves what really is true and whether we should sacrifice some amount of our sense of belonging in light of new information.

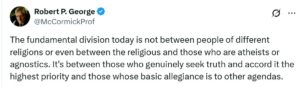

Finally, there is the motivation of truth. Princeton University professor Robert George recently posted on the centrality of commitment to truth:

To be truth-motivated is often unsettling because so many simple questions turn out to be complex upon close examination. We also discover that our perception of truth is heavily shaped by our culture, our genetics, and things outside of our awareness. And for many issues, truth-seeking means recognizing real ambiguity. This is especially true in questions of history.

But despite the difficulty, to be truth-motivated is extremely important for individuals and societies. As psychologist M. Scott Peck said,

Truth or reality is avoided when it is painful. We can revise our maps only when we have the discipline to overcome that pain. To have such discipline, we must be totally dedicated to truth. That is to say that we must always hold truth, as best we can determine it, to be more important, more vital to our self-interest, than our comfort. Conversely, we must always consider our personal discomfort relatively unimportant and, indeed, even welcome it in the service of the search for truth. Mental health is an ongoing process of dedication to reality at all costs.

As of this writing in early 2025, there are many Americans who are still distraught over the results of the 2024 presidential election. Many who voted against President Trump were completely blindsided by the result and were stunned that anyone could have voted for him. Psychologist Sarah Dargouth wrote an article discussing the impact of the election on her therapy practice: “For many, the election results are front and center, the only topic that we discuss. Emotions are generally loud: despair, rage, disappointment, fear, disgust, hopelessness. Past histories of trauma and abuse are rekindled.” When dishonesty, conspiracy thinking, and misattribution escalate together, … we will see people accord leaders the power of a god.

When lying becomes normal

For understanding how a lack of dedication to reality can affect a society, Russia provides an important case study. In its attempt to create a Marxist utopia, the Russian regime under Lenin quickly found that Marxist/Leninist theories about society did not actually work. People did not respond to communism as expected, and Russia became an extremely violent and oppressive system. In that system there emerged a notion of extraordinary lying, called vranyo. In her memoir of living under the Soviet system, Elena Gorokhova reminisces of her university dean in Leningrad: “Like my mother, he comes from the first Soviet generation, from the time when vranyo was still fresh, still a little curly sprout. He comes from the time when it hadn’t yet morphed and metastasized and tunneled its way through our tissue the way my father’s cancer wormed into his bladder and his lungs.”

Gorokhova goes on to give this description of vranyo:

The rules are simple: they lie to us, we know they’re lying, they know we know they’re lying but they keep lying anyway, and we keep pretending to believe them.

Imagine living in a society where relentless lying was the basis for every citizen’s relationship with the state, and imagine the psychological impact of exercising that muscle of constant lying, day in and day out. When in 2021, Russian authorities figured they would be able to capture Kyiv in three days, that was likely due to vranyo among their military planners and analysts. Russians currently do not have a sense of the magnitude of the loss of Russian lives, nor their war’s toll on their country’s long-term economic well-being, also due to vranyo in their public commentary. A prominent public military analyst recently created a presentation on vranyo in the Russian military, pointing to “the culture of constant, incessant lying at all levels of command.”

A warning to the West

The example of Russia serves as an ominous warning to the West, particularly the United States. Currently, we have numerous mechanisms for fact-checking statements of our public figures, but sometimes those are subverted by political interests and ideological bias. In recent years we have seen a shift to open, brazen, unapologetic lying at the highest levels of culture and government, and also increasingly wild claims about what our government leaders are able to do. Presidential candidates regularly claim to be able to steer worldwide markets, stop foreign wars, impose control on the world’s climate, and perform any number of increasingly outlandish feats of governance that are simply not humanly possible to do. In past decades, people making these claims would have been considered fabulists and delusional narcissists, but now we barely raise an eyebrow with each new claim of godlike power.

When we see these trends of dishonesty, conspiracy thinking, and misattribution escalating together, it is not hard to envision a day when dishonest political pundits or leaders actually do claim credit for a hurricane, or for stopping a tornado in its path, or for making an earthquake … and an astounding number of people believe it and accord the leader the power of a god. We sometimes imagine the antichrist as performing wonders and miracles, but perhaps those wonders and miracles will be things that such a leader merely claims after the fact, and his claims are believed by the public because we, with our partisan conspiracy brains, have so fully lost our grip on reality. It is not hard to see why Paul would use the phrase “lying wonders.”

As Latter-day Saints, we sometimes receive encouragement to hasten the Lord’s work to prepare for His second coming. I suggest that the escalating lying of our public figures is mentally conditioning the world in a way that creates an appetite for ever-greater delusions. This may be a hastening of a different work that is preparing the world for the arrival of “the man of sin … the son of perdition,” the antichrist figure prophesied by Paul and John the Revelator, whose defining attribute is spectacular, sensational public dishonesty.

To this, our response should be to maintain a relentless dedication to reality even amid political and cultural trends toward delusion. This is a lonely road for church members to walk, as it is likely to keep us out of alignment with a number of popular movements and communities. But maintaining a grounding in reality can be a way that we function like salt in the world that keeps its savor. Reality and the order it brings can help us to show the world the contrast between the gospel and the mental chaos around us.

The post How Conspiracy Thinking Is Prepping the World for the Antichrist appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →