The year is 2015. Ryan is a passionate Democrat. Jeff, one of Ryan’s closest friends for many years, is an ardent Republican. Both are good people with good hearts—but they have sharply divergent political views.

In a low moment, both Ryan and Jeff explode in an online social media exchange that includes phrases like, “I honestly cannot fathom how any decent person could vote for ________.” Their relationship is deeply damaged. To make matters worse, each seeks counsel from members of his own (fiery) political tribe. Both tribes further demonize the former friend and “other,” who is canceled and socially damned.

It is now 2024. Ryan and Jeff have not spoken in nearly a decade. Both are painfully poorer for the loss of a deep friendship where, once, on occasions as poignant as family deaths, each had lifted and served the other like a brother. All this was lost over disparately checked boxes and a failure to remember that reasonable people can disagree.

The names are changed but this story is true. Perhaps you have seen the same “friend to ‘un-friend’ tragedy” in your own circle and have names of your own to throw on the waste pile containing the decaying remnants of Ryan and Jeff’s broken bond of brotherhood.

America: The Dream, the Vision, the “Great Idea”

As brothers and sisters in the American family living in a land unlike any other, we must individually and collectively be more civil, more wise, and more honorable than we have been in recent elections. There is a better way.

America is not only a land—it is a dream, a vision, a sacred yearning. Paul Hewson (better known as Bono), a 2006 Nobel Peace Prize nominee and winner of the 2008 Nobel Man of Peace Award, has frequently written and sung about this vision. As a youth, Bono saw his native Ireland torn by Catholic-Protestant intolerance that escalated to violence and resulted in bombing-related deaths among some of his closest friends and literal neighbors. These travesties presented a poignantly painful and perplexing puzzle for Bono as a child of a Catholic-Protestant interfaith marriage. Surely, he hoped, humankind could do better than hatred, violence, and blood-soaked ground. Bono recently wrote of both his native Irish home and the American dream:

Ireland is a great country, but it’s not an idea. Great Britain is a great country but it’s not an idea. America is an idea. A great idea. … America is a song yet to be finished. … Perhaps America is the greatest song the world has not yet heard. … (Surrender, pp. 463-464).

For Bono and many around the globe, America has offered and can yet offer light and hope via the religious and political tolerance, civility, and pluralism promised in the American motto E pluribus unum—from many, one. This dual-fueled flame of unity and plurality—of the right to hold sacred personal conviction coupled with authentic tolerance of others to believe differently—requires unwavering and acute diligence and effort.

Selling Hate Versus Honoring Different Roots

E pluribus unum is not a promised land, nor is it a birthright. It is the apex of a mountain that must be collectively ascended. Without intentional upward effort, the heavy gravity of political, religious, racial, and ideological differences drag us downward to disintegration and entropy. Indeed, the Neo-Nazi leader Lincoln Rockwell once said to Alex Haley, “The easiest thing in this world to sell is hate.”

Gratefully, Alex Haley refused to take the “easy” path of hate. Perhaps no American artistic product has wielded more impact and unifying force than Alex Haley’s subsequent effort, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel (and landmark TV mini-series) Roots. Through Roots, America, the “great idea” was challenged, and “America the People” was confronted with the horrors of African slavery and invited to step onto the painful ground of African Americans in deepened empathy and respect. Many accepted that invitation, and, in some ways, America became a better version of herself. We still have rivers to cross, however.

It is relatively easy to have warmth, affection, and sympathy for a person or group with whom we share religious, racial-ethnic, or political ties. However, we find nowhere in the writings of world religions a statement that reads, “Blessed is the one who only loves the easily lovable.”

By contrast, various expressions of the Golden Rule—exhorting us to respectfully treat others as we would be treated—are prevalent across religious traditions. While it is frighteningly easy and destructive to hate, it is deeply honorable and constructive to develop friendships and relationships of trust with those whose experiences, beliefs, and views differ from our own. Love of one another—including those we are tempted to see as “the other”—is an ascension worth the required personal and collective effort.

Striving to Surmount the Empathy Wall of Political Differences

The philosopher Terry Warner echoed, “To the immature, other people are not real.” Similarly, one obstacle to achieving the aim of E pluribus unum is a concept the Berkeley sociologist Arlie Hochschild has called “the empathy wall”—a barrier that keeps us from truly seeing others as “real.”

While holding a strong progressive orientation herself, Hochschild made the concerted effort to live among, share meals with, and interview passionate (circa 2015) Tea Party supporters in Southern states with petroleum-based economies. In her book-length study, Strangers in Their Own Land (2016), Hochschild actively avoided the tendency of many social researchers to repeatedly steal the microphone from her participants, like a “diva soloist.”

Instead, Hochschild listened to the voices of others. She listened not only for hours but for months. She probed, prodded, dug, and came to better understand those persons who allowed her onto their porches and into their homes. Hochschild did not change her own political views, but she did pay the steep price to climb over “the empathy wall.” Her example resonates with the philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s statement:

[A]ny self-knowledge worth the name tells you that others are as real as you are, and that your life is not just about you, it is about accepting the fact that you share a world with others, and about taking action directed at the good of others.

Given the divisive and hostile climate that too often prevails in contemporary America, it has never been more important to intentionally surmount the empathy wall that can prevent us from “sharing a world” with others while also blinding us from viewing others as entirely “real” as we are.

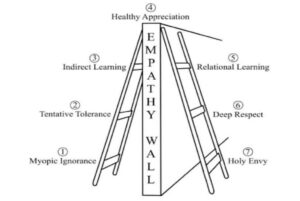

Arlie Hochschild’s personal investment in the kind of expensive pluralism required to surmount the empathy wall is remarkable and motivational. Based on 25 years of interviews with religiously, racially, and ethnically diverse families in their homes, our team developed a visual representation of ascending over Hochschild’s “empathy wall” called the empathy ladder (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Empathy Ladder

An Overview of the Empathy Ladder

The journey offered by the empathy ladder leads us from the bottom rung of myopic ignorance to the second rung of tentative tolerance. From tentative tolerance, we can step up to indirect learning. Indirect learning can rise to healthy appreciation, and one step above healthy appreciation is relational learning. The descent to the personal, sacred ground of another person (on the other side of the empathy wall) includes stepping from relational learning to deep respect. From deep respect, we finally step onto the sacred ground of holy envy. Each additional step on the empathy ladder deepens our ability to appreciate another person or group. The more often we navigate the empathy ladder, the greater the enrichment we receive to our minds, hearts, and relationships.

Stephen Covey posited that the most important principle in human communication may be: “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” One person making this gracious effort can have ripple effects. Indeed, we have reported from our interviews with hundreds of strong married couples from diverse races and religious traditions that one of the foundational lessons these exemplary families illustrate is “the principle of lived invitation.” Namely:

“Our behavior is permission to others to behave similarly … but it is more than that. It is an invitation to do so.”

Our research team has further noted that “[L]ike individual persons, each religious tradition has its own quirks, blind spots, and foibles. … [T]aking potshots at these perceived weaknesses is a cruel game that can rapidly turn into a blood sport.” Indeed, these are games where no one wins. Instead of amplifying prevalent weaknesses we observe in other denominations or persons, we posit that it requires intention and strength to focus on the strengths of others. The effort to develop the kind of deep respect that is rarer than love can lead us to the final step of developing holy envy.

We believe that a full-souled expression of holy envy results from deeply honoring the best of one’s own religious tradition and people, coupled with a broadminded and large-hearted desire to also acknowledge, honor, and be elevated by the best of other religious traditions and people as well.

Our team has observed and documented that religion wields what de Tocqueville called a “peculiar power”—a power that can destroy or construct, harm or heal. Like religion, political passion also wields peculiar power. Can the political empathy wall be surmounted so that contentious division can be replaced by “deep respect”?

A Political Vision of Surmounting the Empathy Wall

We began this report with the tragic reality of Jeff and Ryan’s terminated brotherhood— former friends who opted to lob verbal grenades onto the other side of the empathy wall instead of making the effort to surmount the wall and see the person on the other side as “real.” We now turn to an alternative model for the 2024 election cycle.

Pam Monroe spent her early career in Progressive politics with an especial passion for policy designed to help and lift those in poverty. Pam’s career eventually shifted to academia where she would hold an endowed professorship at LSU. Pam was widely and highly esteemed by colleagues (liberal, moderate, and conservative) and, in 2004, was elected President of the National Council on Family Relations (NCFR) while still in her 40s. Throughout her career, Professor Monroe’s focus never shifted from her concern for those in poverty. But caring for the poor was not Pam’s only love. “Everything I am,” she has repeatedly said, “is because of the love of Jim Garand.”

Jim Garand, like his wife Pam, has held an endowed professorship at LSU for decades. Like Pam, Jim was elected President of a large academic organization (The Southern Political Science Association) at a relatively young age. Unlike Pam, however, Jim is a committed Conservative—one who has frequently had to look beyond his party’s primary nominees in recent elections.

Both Pam and Jim are powerhouses. Both are articulate, enigmatic, passionate and have no difficulty expressing themselves and speaking their keen minds. Given these realities, it may seem that the stage was set for an epic battle and a very brief marriage—one likely featuring pyrotechnics. However, the years have yielded something quite different. You see, both Pam and Jim know how to listen to each other with deep respect. In connection with queries about this, Pam responded,

I fear you give us too much credit—rather, that you give ME far too much credit. Jim is the peacemaker. I’m just not an idiot.

Further, from Pam’s perspective, “We haven’t bridged a gulf quite so wide as the essay references.” Perhaps Pam is right. She usually is. However, she and Jim are the closest thing that this author has ever seen to embodying the elusive American ideal, so we will continue. Jim responded,

Pam likes to say that marriage is the best hard work that one ever does, and dealing with personal political division in today’s polarized United States is not easy and reflects that “hard work” theme. Sometimes it involves one of us listening without comment to the other rant over something that one of us finds outrageous. Sometimes, it involves not bringing up a touchy topic when emotions might be raw. It also involves not trying to score cheap political points or use “zingers” on the other. In intense political discussions, it can be difficult to show this kind of restraint.

To recap: From Pam and Jim, we have references to peacemaking, bridging gulfs, shared “hard work,” and often “listening without comment” with mutual “restraint.” It sounds a bit like Durant’s “river of fire” wisely banked at a thousand turns. Notably, a profound respect for each other and their relationship is evident and woven into both partner’s comments.

Pam and Jim’s marriage has subsequently inspired deep respect and holy envy in many who have observed their blessed union over their more than 40 years of marriage. Pam and Jim offer a hope-filled reality to an America plagued by political division. Pam and Jim both play fair and acknowledge many conspicuous flaws in both major parties … including certain candidates their preferred party has nominated. Pam and Jim’s political values are different, but both of these remarkable persons have surmounted the empathy wall so frequently for each other that they also share a great deal of sacred ground. Whatever political winds have blown over the past four decades, they have refused to surrender the rock of their respect-filled relationship.

The Purpose and a Plea

It is uncertain which parties and candidates will prevail in various elections in 2024 or during the next contention-filled election cycle. Whatever the poll results this month or in the future, Pam and Jim will continue to “seek first to understand,” they will continue to warrant and offer deep respect, and they will continue to love one another. If they can do so for four decades, maybe the rest of us can do likewise with the politically opposing loved ones that we have not yet foolishly canceled.

In the contention-riddled face of the cannibalistic political “now,” my purpose here is a plea that we each honor the timeless, sacred, and inherent worth of relationships between persons. May we be wise enough to “do politics,” civility, and respect in a way that embodies the American ideal. A question for each one of us remains:

“Am I willing to climb the empathy ladder for someone else?”

A passage from the Jewish Zohar reads:

A wise man knows for himself as much as is required, but the [person] of [true] discernment apprehends the whole, knowing both his own point of view and that of others. … He apprehends the lower world and the upper world, his own being, and the being of others.

May we all more wisely and respectfully discern and “apprehend” the faith, the political beliefs, and the being of others. May we make the effort to surmount the empathy wall rather than lobbing verbal grenades over it. May we move closer to the “great idea” of America.

The post The Great Idea of America: Lessons from a Mixed-Politics Marriage appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →