I have always had an interesting relationship with my paternal grandfather. Interesting is an ambiguous and undescriptive word, though it works better than other overly intense adjectives like strained, artificial, or neglectful. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that I have an uninteresting relationship with my grandfather or that we don’t have much of a relationship at all, though even this would go too far, and so I settle for “interesting.”

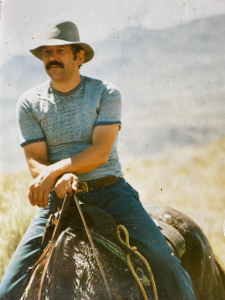

By the time I was born, Grandpa’s life story had more or less been written. He grew up in a large family in the Mountain West, rode horses, and teased his sisters. When he was nineteen, he lived in Scotland for his two-year missionary service for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In Scotland, he met my grandmother, helped facilitate her move to the United States, and within a few years, married her.

Grandpa maintained a small ranch and a love for horses his entire life. He worked odd jobs that never lasted long and raised seven children with my grandmother. Later, when my dad was in Brazil for his own missionary service, Grandpa divorced grandma, moved in with his girlfriend turned common-law wife, and slowly drifted away from his family. This was his state of being as long as I knew him.

If you went to visit Grandpa in his Idaho home tucked back in the barren hills southeast of Boise, he would welcome you as a gracious host. And every year—maybe every other—he made a single day’s appearance at a Farnsworth family reunion. But that was about it.

Because of his persistent absence, I knew my grandpa more through stories and his mythical legacy. Most canonized accounts were tales of his amazing grit, like the time he barreled down a hill like The Man from Snowy River to save a boy scout or the time he crawled on his hands and knees to an upstairs window of his house to shoot a horse who had just bucked him off. These, and many like them, were the legends we heard at Farnsworth gatherings.

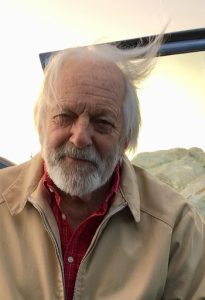

When I turned eight, he sent me a silver dollar as a present, and each December, he sent all of his grandchildren a $10 McDonald’s gift card. He never attended a birthday, wedding, sporting event, graduation, or significant occasion in my life or the life of any of my siblings. It wasn’t until I was older that I felt any disappointment in this. When I was young, he was simply Grandpa, the rough, white-bearded man who’d give you a scruffy hug whenever he saw you. Plus, he was the only grandpa I had; my mom’s father and my namesake passed away the year I was born.

Despite all this and the infrequent visits, I felt a strong connection with Grandpa. This isn’t surprising, as at that age, about eight years old, I possessed an embarrassingly tender love for extended family. This manifested itself most with my cousins, aunts and uncles, and grandparents, who lived in Idaho and who we saw only once or twice a year.

After a family reunion or a weekend trip, I would sit in the back of our minivan and bawl because we had to say goodbye to him. My mom had this silky, beige blanket with a picture of two cats sitting around a fishbowl which I would drape over my head so my parents or siblings wouldn’t see me cry. Of course, they all knew what was happening and heard me blubbering like a seal in the corner of the van. All of that is to say that even though Grandpa and I didn’t really see each other all that much, I felt an immense attachment.

To try and keep in more regular contact, I took to sending him hand-written letters. In response, he sent me photos and postcards and included some sketches of motorcycles that his stepson had drawn, which I traced and attempted to emulate. This lasted maybe a year before the habit faded.

Another reason I felt so close to Grandpa was that I thought I could help him. From a young age, I felt hyper-aware of Grandpa’s shortcomings and knew that he wasn’t living up to the commitments our family and faith espoused. This, I believed, could be reversed by heartfelt prayer. From ages seven to twelve, I asked God almost every night that Grandpa would come back to the Church. If I ever forgot to include that in my prayers, I guiltily thought that this single omission would undermine the entire effort.

Grandpa never came back to church, and eventually, I stopped asking God to help. I sometimes wonder if I stopped partly because I wasn’t willing to admit that the prayer wasn’t answered. You see, if I stopped praying, then God wasn’t letting me down. He could remain a God who answered prayers; I just wouldn’t be praying for that particular blessing.

Over time, the internal activity in my mind changed from “when will Grandpa come back to church?” to “why won’t Grandpa come back to church?” and a more hard-hearted, “well, if Grandpa doesn’t want to change, that’s on him, not me.” It was not God’s withholding or my own lack of faith that had so far yielded no results. It was Grandpa and his own stubbornness. Only he was to blame.

Though I was becoming more and more jaded about his eternal prospects, I still attempted to maintain a relationship with Grandpa. One memorable moment came a few months before I left for my own missionary service to New Zealand when my dad and I visited Grandpa in Idaho.

The night is still vivid to me. We arrived after the sun had set behind the bald, dusty foothills that surrounded his house. The home had continuous floor-to-ceiling windows on the main level, which enlarged the darkness outside the house and intensified the light within. We sat around a wooden table for dinner, and he shared stories from his time in Scotland. After dinner, I played him a few songs on the guitar. I felt something that night I had never felt before: undivided attention and affection from a grandfather. That night in bed, the thought crossed my mind that I would likely never feel it again. How often do we limit our understanding of God’s love simply due to the failings of our own imagination?

In the years after I returned from New Zealand, I saw Grandpa only a handful of times. Once at a Christmas party, on a quick visit to his house on our way to family in Boise, and another couple of times at family reunions. Gratefully, he was able to meet my wife and son. Nevertheless, I privately condemned his seemingly apathetic attitude towards both his family and his church.

Then, less than a week into 2022, my dad sent a text to our family group saying that Grandpa had been taken to the hospital with low oxygen levels and general intolerance to food brought on by COVID-19. We learned a few hours later that complications from COVID caused a major heart attack and kidney failure. A day later, Grandpa was gone.

In the 30 hours between the first text and the last, I felt a slew of different emotions. In no particular order, they went something like:

- Apathy towards death. Doesn’t it claim us all?

- Guilt that I hadn’t done more in the last five years to stay close to Grandpa.

- Anger that he never corrected his ways.

- More guilt that I was angry and judgmental.

- Self-pity that I was somehow suffering more than others because I had once had a strong relationship with him.

- Feeling bad that I tried to compare my own grieving to that of my family.

- Amazement and then guilt that I had never stopped to consider the nature of my own father’s relationship with Grandpa.

- Grateful that I have such a remarkable, involved father.

- Disbelief that Grandpa could actually be dying. Hadn’t he proven unkillable in all his wild shenanigans? As he loved to say, you can’t kill a weed.

- Terrible sadness that he was gone, and gone so quickly.

Mostly, I still felt how I had the last several years: consigned to the fact that Grandpa had done wrong by his faith and family and that he would suffer the just recompense for his mistakes.

My dad did not share the same view. In a series of texts and calls, he laid out the case why my sibling and I should not be so quick to cast judgment. Yet stronger than the reasons he gave was the pure and holy hope he possessed. Dad did not want to condemn Grandpa, and so he hoped for a God who would ultimately not condemn him either. He put it simply, quoting a Mennonite pastor, “Never give up on Jesus.”

That stirring phrase contains a multitude of compassion and wisdom. It meant that only God had a perfect understanding and could see Grandpa’s whole life, including the thoughts and challenges hidden from his children and grandchildren. It meant that if my dad, or any of us, were to judge Grandpa harshly, we would have, in fact, given up on Jesus. It meant we should not limit our own faith in a God we profess to be all-knowing and all-loving.

Yet so many still wonder: what is the true nature of God? Is He justice or mercy, condemnation or understanding, factual or contextual—or all the above? Is he the God who says, “I the Lord cannot look upon sin with the least degree of allowance,” or the God who later, in the same book of scripture, says, “notwithstanding their sins, my bowels are filled with compassion towards them”?

Or, of course, both? If our gaze can reach beyond our natural vision, we’ll recognize that both statements are true—pointing us towards a divine harmony that makes up a heaven that mortals can actually conceive of letting them in. When it comes to the joint operation of mercy and justice, perhaps more important than even what is ultimately true is the question of which aspect of God we choose to focus on.

In my case, I had chosen the God of unbending justice, and my father had chosen the God of compassion. Which focus was right? Neither of us has the power to enact either scenario; we are not gods, nor are we Grandpa’s jury. We do, however, have to live with the consequences of our thinking.

We have, as Dan Ellsworth recently wrote, “a limited understanding about what we and others are even capable of desiring.” Lacking clarity about Grandpa’s choices, circumstances, and desires did not free me from my own clear obligations to forgive.

Had I maintained my cold-hearted judgment, what did it say about me? What did it say about the kind of world I wished to inhabit or the limits of my own love and tolerance? What did his emphasis on compassion say about my father and his world?

The differences are striking. His is a world where we forgive the shortcomings of others, especially the shortcomings that cause us the most harm, where we plead with God to extend mercy to us and those we love—with an unending hope that it will be true.

Is it blasphemous to imagine such a God? To emphasize this side of His character? I’m not suggesting God gives no commandments or has no responsibility to justice. To eliminate the God of justice, law, and commandments would be to eliminate God in His entirety or veer too far into universalism, where we may become, as Saint Louis University professor Michael McClymond writes, “less concerned with all men’s being united to God than with all men’s being united to each other.”

I am suggesting that we let God handle all of that Himself. Judgment is God’s burden to bear. That jurisdiction is not granted to mortals. Ours is a different burden, the burden of forgiveness, because of us, “it is required to forgive all men.”

Forgiveness often feels harder than judgment, but sometimes I wonder why? Why should we be so eager to play referee? Why do we unnecessarily burden ourselves with judgment when we could emulate mercy?

Above all, where should our primary focus be? I read a poem by Wallace Stevens recently that I took to be rather atheistic, but on second reading, especially after this experience with my grandfather, I see it as spiritually hopeful. He writes:

We say God and the imagination are one …

How high that highest candle lights the dark.

This idea, he says, is:

…a single thing, a single shawl

Wrapped tightly round us, since we are poor, a warmth,

A light, a power, the miraculous influence.

A secular mind might read those lines and suggest there is no God, that He is only imagination. I read those lines and aspire to imagine the most merciful God I can. How often do we limit our understanding of His love simply due to the failings of our own imagination? In what ways can a little more imagination help us see and know God better?

I have come to relish the mercy of God just like my father and feel a weight lifted from my back. I love my grandpa, yet by allowing my imagination to focus on punishment, I willed into existence a vengeful God that aligned with my own frustrations and resentments towards him. Ironically, I’m back to where I was as a child, offering prayers for Grandpa that are full of concern and love and believing in a God who can answer those prayers.

In turn, I also find myself wishing for God’s mercy for my family, friends, and even myself. Isn’t that ultimately what we all want in our own lives? For God to say, “I understand, and I forgive.” Should I not aspire towards this same divinity to forgive others, just as I wish Grandpa and myself to be forgiven? At least, this is what I imagine.

The post Forgiving Grandpa appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →