“Even as Moses Did”: The Use of the Exodus Narrative in Mosiah 11-18

by Sara Riley

(This is from a presentation given at the 2018 FAIR Conference)

In this presentation I hope to answer the following questions:

- How is the Exodus narrative used in Mosiah, both structurally and thematically?

And by that I mean, how is the structure of the book of Exodus similar to these chapters in Mosiah, and how are the Exodus themes used in the Book of Mosiah? - Were these Exodus motifs and allusions intentional?

And while we cannot necessarily as a reader be 100% positive concerning the intent and purposes of the author or authors of the Book of Mosiah, I hope to establish that these allusions may plausibly have been intentional. - And if it is intentional, why would they use the Exodus narrative for this particular account?

Limitations

But before I proceed, there are some limitations to this approach that I need to bring up.

First is translation and language. There are limitations to how much we can pinpoint the finer elements of the Book of Mormon syntax and grammar.

Also, comparing specific words is a challenge since we do not have the original text language of the book of Mormon, and we have to rely on the English translation.

Also, we don’t know all the sources that were used to write the Book of Mosiah, and we also don’t know what version of the Pentateuch (the five books of Moses) the author had for Mosiah.

And since these are both historical accounts, we can’t compare event by event per se, since they’re both treated as histories for the people. Some correlations between persons and events may blend a bit together while we are comparing these allusions.

Lastly, we don’t know how much Mormon, who abridged the Book of Mormon, has influenced the text, or if the original author was alluding to the Exodus story.

What is the Exodus?

So now that those are out of the way, one last thing is, what is the Exodus? What does the Exodus story encompass?

Unlike the movie Ten Commandments, it doesn’t end at the golden calf scene; the Exodus account is spread over the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy and some Joshua. I think it’s fair to say most scholars agree that it can be seen as, “encompassing everything from the bondage in Egypt up to the preparations to cross the Jordan after forty years of wilderness wandering” (S. E. Lowenstamm, The Evolution of the Exodus Tradition, p. 32, n. 18). So when I’m talking about the Exodus, that’s what I mean, everything from those, from that.

Availability of the Exodus Record?

All right, first question that should be asked is, “Did the author of Mosiah even have the Exodus source?” We know initially Nephi brings back the brass plates from Jerusalem and he mentions in 1 Nephi 5 that it contained the five books of Moses.

“Lehi, took the records which were engraven upon the plates of brass, and he did search them from the beginning. And he beheld that they did contain the five books of Moses, which gave an account of the creation of the world, and also of Adam and Eve, who were our first parents” (1 Nephi 5:10-11).

Although their version might be slightly different from the one we have now, so that also could be a little bit of a limitation, we also must ask, did King Zeniff and his people have copies of the brass plates or other scriptures with them when they moved from the land of Zarahemla back to the land of Nephi?

We know that they are at least very familiar with the story, as King Limhi, who is the grandson of King Zeniff, mentions the Exodus narrative when he speaks to the people in Mosiah 7.

“…that God who brought the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt, and caused that they should walk through the Red Sea on dry ground, and fed them with manna that they might not perish in the wilderness…” (Mosiah 7:19).

And lastly, the courts of Noah had, or at least claimed that they had, an understanding of the law of Moses which is contained in the Exodus story in Mosiah 12.

“And they [Noah’s priests] said: We teach the law of Moses” (Mosiah 12:28).

So now let’s examine the similarities between the two accounts in detail.

In Exodus we first begin with the oppressive pharaoh, the new pharaoh who doesn’t like the Israelites, who doesn’t know who Joseph is, as the text says. And he oppresses them with hard labor and forcing them to build a palace city. The story in Mosiah also begins with oppressive and wicked King Noah who lays heavy taxes on the people and coerces them into laboring to construct many costly buildings.

Also, we are introduced to Moses, he kills an Egyptian and flees to Midian in fear for his life. Also, likewise, Abinadi prophesies to the people and he flees from them in fear of his life.

Next, Moses is commanded to return and to deliver Israel. And Abinadi is commanded to return and prophesy to the people.

Moses and Aaron compete against Pharaoh’s court priests and Abinadi withstands King Noah’s priests.

The firstborns in Egypt die and the Israelites leave Egypt; Abinadi is executed and Alma escapes.

The Israelites pass through the Red Sea; Alma’s followers are baptized.

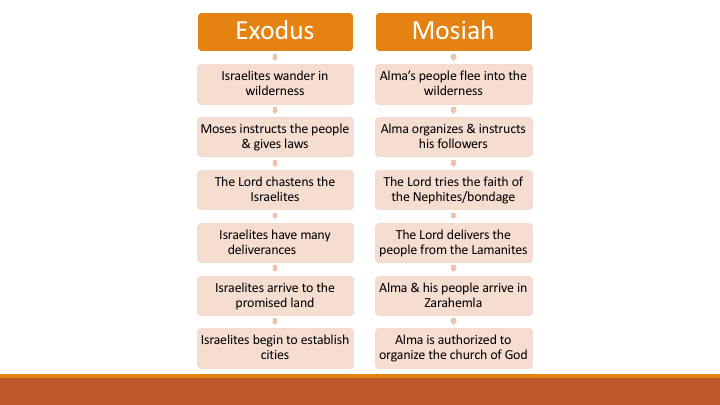

The Israelites then wander in the wilderness; Alma’s people flee into the wilderness as well in fear of King Noah.

Moses instructs the people and gives laws; likewise, Alma organizes and instructs his followers.

And throughout the Exodus story, the Lord chastens the Israelites as we read on multiple occasions. And the Lord also tries the faith of the Nephites when they’re in bondage, as we read in the text.

The Israelites also have many deliverances and the Lord delivers the people from the Lamanites when they’re in bondage to them.

The Israelites then arrive to the promised land, and Alma and his people arrive in the land of Zarahemla.

And next, last of all, the Israelites begin to establish cities in the promised land, and Alma is authorized to organize the church of God.

So based on these similarities, it seems pretty reasonable to suppose that the author of Mosiah was drawing from the Exodus narrative. This use of the Exodus can be seen as unifying the structure and the layout of the chapters in Mosiah.

Explicit References to the Exodus

While many of the references of the Exodus in Mosiah are more subtle, there is specific mention of the Exodus in Mosiah chapters 12 -13.

One of the most explicit comparisons to the Exodus is in Mosiah 13:5 when Abinadi is testifying to the priests and his face is compared to Moses’ when he was on Mount Sinai, which is: “…his face shone with exceeding luster, even as Moses’ did while in the mount of Sinai, while speaking with the Lord.”

Also, Abinadi specifically references the Exodus a few times in his speech, showing even Abinadi had the Exodus in mind while preaching to the court: “But now Abinadi said unto them: I know if ye keep the commandments of God ye shall be saved; yea, if ye keep the commandments which the Lord delivered unto Moses in the mount of Sinai…” (Mosiah 12:33).

And also, Abinadi continues: “…it was expedient that there should be a law given to the children of Israel, yea, even a very strict law; for they were a stiffnecked people, quick to do iniquity, and slow to remember the Lord their God;” (Mosiah 13:29).

King Noah and Pharaoh

So now that we’ve gone through the overarching structure of these chapters in Mosiah, I will go chapter by chapter examining the allusions to the Exodus narrative. We will begin in chapter 11 of Mosiah.

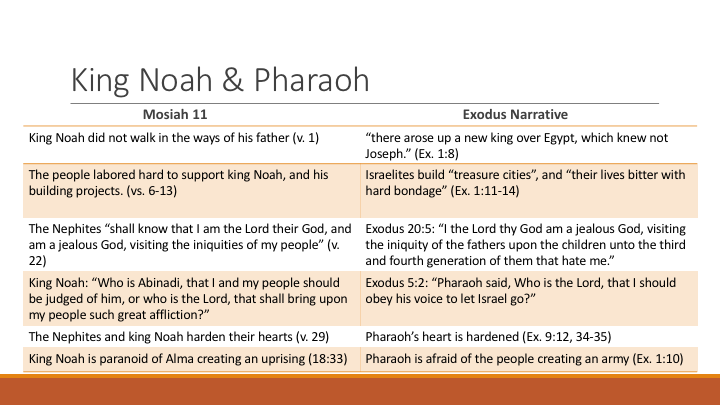

As mentioned earlier, the book of Mosiah portrays King Noah like the oppressive and hard-hearted pharaoh of Egypt. The text begins in verse one by stating that King Noah did not walk in the ways of his father. And likewise “…there arose up a new king over Egypt, which knew not Joseph” (Exodus 1:8).

As mentioned before, the people labored hard to support King Noah and his building projects (vs. 6-13) and also the Israelites were in heavy bondage; they built “treasure cities,” and “their lives [were] bitter with hard bondage” (Ex. 1:11-14).

And then the Nephites “shall know that I am the Lord their God, and am a jealous God, visiting the iniquities of my people” (v. 22) and that is Abinadi quoting Exodus 20:5 which says: “I the Lord thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me.”

Also, King Noah says, “Who is Abinadi, that I and my people should be judged of him, or who is the Lord, that shall bring upon my people such great affliction?” And this was one of the first things that kind of tipped me off that they were using the Exodus when I was first starting to study this, when he says, “Or who is the Lord?” And because the pharaoh says, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice to let Israel go?” (Ex. 5:2)

And then next, it mentions that the people and King Noah hardened their hearts, and here in Exodus, it says Pharaoh’s heart is hardened on multiple occasions; his heart becomes more and more hardened (Ex. 9:12, 34-35).

And last of all, King Noah is paranoid of Alma creating an uprising (18:33) and Pharaoh is afraid of that exact same thing. He’s afraid they’ll create an army (Ex. 1:10); they’ll be rebellious and that’s one reason why he does not want to let them go.

References in Mosiah 12

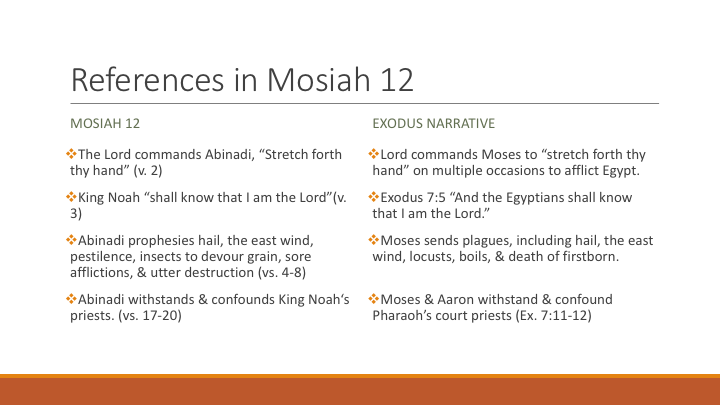

In addition to similarities between King Noah and Pharaoh, there are more subtle allusions to the Exodus narrative in Mosiah. Mosiah 12 begins with the Lord commanding Abinadi to “stretch forth thy hand” (v. 2) and we see throughout the beginning of Exodus the Lord commands Moses to “stretch forth thy hand” on multiple occasions to afflict Egypt.

And the Lord says King Noah “shall know that I am the Lord” (v. 3) and the Lord says to Moses in Exodus 7, “And the Egyptians shall know that I am the Lord” (v. 5).

Next, Abinadi prophecies hail, the east wind, pestilence, insects to devour grain, sore afflictions, and utter destruction (vs. 4-8). And likewise we are very familiar with Moses and the plagues which include hail, the east wind, locusts, boils, and death of the firstborn.

Lastly in this chapter, Abinadi withstands and confounds King Noah’s priests (vs. 17-20); they are so surprised at his answers. And in Exodus, Moses and Aaron withstand and confound Pharaoh’s court priests (Ex. 7:11-12); they have a fun little showdown with serpents.

“Garment in a Hot Furnace”

But before I begin with this next slide, I would like to credit Jack Welch and Gordon Thomasson and Robert Smith for introducing me to the next allusion I’m about to discuss (See John W. Welch, Gordon C. Thomasson, and Robert F. Smith, “Abinadi and Pentecost,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992]) which is when Abinadi prophecies that “the life of King Noah shall be valued even as a garment in a hot furnace” (Mosiah 12:3). Now besides being quite a threat to the life of a king, we know that in Exodus 19, Mount Sinai becomes a furnace when the Lord appears. “And mount Sinai was altogether on a smoke, because the Lord descended upon it in fire: and the smoke thereof ascended as the smoke of a furnace, and the whole mount quaked greatly” (Ex. 19:18).

Also in this story, the Israelites sanctify themselves and wash their clothes in preparation (Ex. 19:14) to be able to abide the presence of the Lord on Sinai. And perhaps Abinadi meant to imply that King Noah was not sanctified and not worthy to be a ruler of the people, and would not be able to withstand the presence of the Lord. So, pun intended, that was a major burn for King Noah.

Exodus Motifs in Mosiah 13-16

So we’ve discussed specific structure and phrases and narrative similarities to the Exodus narrative, but there are also some overarching themes that climax in Mosiah chapters 13-16. And these motifs, I think they’re pretty generally accepted in the scholarly discussion; I got these exactly from the Anchor Bible Dictionary on Exodus, so it’s not just me saying that these are the themes for Exodus.

Motif 1: God’s Presence with His People

While there are many events throughout the story of the Exodus, one of the common factors in each is the theme of God’s presence with His people. Everything from God delivering the Israelites multiple times, even during times of rebellion, God demonstrates His faithfulness to His covenant people. Likewise, Abinadi testifies that God Himself shall come down among the children of men and shall redeem His people. And again, I’ll say “God Himself shall come down among the children of men.” Furthermore, when Abinadi’s face shines as Moses’ did, it recalls when Moses descended Mount Sinai the second time, when God’s presence was there.

Motif 2: Deliverance from Bondage

This theme of deliverance from slavery in Exodus is more focused on physical bondage, and even portrays God as the divine warrior. The text mentions that the Israelites were armed for battle, but in Exodus 14, God says, “I the Lord will fight for you.” In Exodus 15, the Israelites sing, “The Lord is a warrior, the Lord is his name.”

The Book of Mosiah also proclaims deliverance from spiritual bondage. And the Messiah going forth before his people to overcome the battle of evil and deliver them from their iniquities and Christ who has broken the bands of death.

Motif 3: The Giving of the Law

The law is the principle part of the events in Exodus from the giving of the law, to the reception of the law on Mount Sinai, and special instructions to become a holy nation. Additionally, we see Abinadi giving the law of the ten commandments to the king’s court, and also further expounding the purposes for the law of Moses as a type of Christ.

Alma, “A Young Man”

So next we are introduced to Alma, one of King Noah’s priests. Mosiah 17:1 begins, “But there was one among them whose name was Alma, he also being a descendant of Nephi. And he was a young man, and he believed the words which Abinadi had spoken.”

We are also introduced to Joshua in a similar manner: “…but his servant Joshua, the son of Nun, a young man, departed not out of the tabernacle.” (Exodus 33:11)

Another similarity I have found between Alma and Joshua is them writing down the words of the their predecessors. So Alma, “he being concealed for many days did write all the words which Abinadi had spoken” (Mosiah 17:4).

And likewise, “Joshua wrote these words [meaning the words of Moses] in the book of the law of God…” (Joshua 24:26).

So Joshua helps bring the children of Israel across the Jordan, and begins to set up the lands of their inheritance in Israel. And as we see further on in the story, Alma brings the people safely to the land of Zarahemla, and begins to set up churches in the land.

However, I would like to note that while Alma is compared to Joshua in the sense that he was Abinadi’s successor as Joshua helped complete Moses’ mission for the people, the Mosiah text doesn’t compare event by event with Joshua later on, as far as I can tell.

Abinadi Prophesies During Pentecost

So another important point to note is that Abinadi probably prophesied during Pentecost, which is also called “Feast of Weeks” in Exodus. And if you would like more information I have on the bottom a reference to a really good article “Abinadi and the Pentecost” which, if you’d like to learn a little more about that you can read it online for free, it’s a really good read. (See John W. Welch, Gordon C. Thomasson, and Robert F. Smith, “Abinadi and Pentecost,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992])

So the time of Pentecost gives another aspect to the Exodus allusion, as Moses gave the ten commandments around the season of Pentecost (Exodus 19:1). Thus, Pentecost probably also celebrated the giving of the law of Moses, adding another layer of understanding for when Abinadi gives and explains the ten commandments to King Noah’s court.

We also know that the festival appears to have been a three-day event (Exodus 19:11), which could explain why Abinadi’s trial was postponed for “three days” (Mosiah 17:6).

Another part of the festival was that it celebrated the concluding of the grain harvest, which may help to explain why the people were infuriated at Abinadi for prophesying famine; you know, insult to injury, they’re celebrating the harvest and he says, yeah, you’re going to be having famines (Mosiah 12:6).

God’s Covenant People

I think this is one of the most important parts of the Exodus: the people making covenants to obey God.

Not long after entering the wilderness, the Israelites made covenants. This covenant relationship with God is also reflected in this Mosiah narrative not long after Alma’s people flee into the wilderness, beginning in Mosiah 18.

The Passing of the Red Sea and Baptism

And as was noted a little bit earlier on, the passing of the Red Sea and baptism have some correlation. The passing of the Red Sea has been seen as a baptism-like experience. For instance, Paul in 1 Corinthians 10 says: “Moreover, brethren, I would not that ye should be ignorant, how that all our fathers were under the cloud, and all passed through the sea; And were all baptized unto Moses in the cloud and in the sea” (1 Cor. 10:1-2).

Not only Paul has seen this parallel, but also others have seen this at the beginning of the Christian era, specifically the Jewish community. Besides circumcision, they included a purification rite of initiation.

This is a quote from [George] Foot Moore who explains, “The purpose of this initiation was to cause the proselyte to go through the sacrament received by the people at the time of the crossing of the Red Sea. The baptism of the proselytes was then a kind of imitation of the Exodus. This is important in showing us that the link between baptism and the crossing of the Red Sea existed already in Judaism.” And I’d also like to note that as another layer of understanding for baptism, perhaps they also saw it as a deliverance in some ways, a spiritual deliverance, when they made the covenant of baptism.

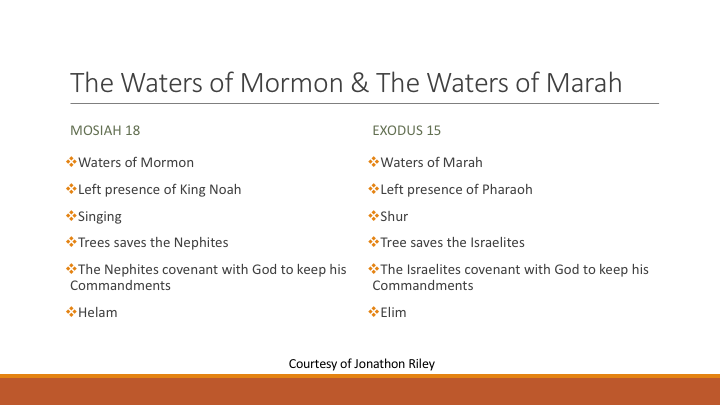

The Waters of Mormon and the Waters of Marah

Also, here are some connections to the Waters of Marah in Exodus 15 and the Waters of Mormon in Mosiah 18. These similarities, while not immediately apparent, are subtle and insightful.

It begins with Alma gathering his people to a water source in a place called Mormon. The Syriac translation of Exodus 15 shows that Marah was likely pronounced as Mor-ah, which is pronounced like the first half of the name Mormon. So already at the beginning of this chapter there’s a signal that the text is making connections to this story.

Next, another similarity is that both groups arrive at a place of water soon after fleeing the wicked rulers. The Waters of Marah is stated being in the wilderness, and the Waters of Mormon noted in verse 4 as “being in the borders of the land, having been infested by times or at seasons by wild beasts.” So perhaps it might have been in some kind of wilderness layout. Also, the Waters of Mormon is described as the fountain of pure water, and the Waters of Marah were purified, or made sweet, when Moses cast a tree into the water.

In the Exodus narrative, the Israelites are traveling in the wilderness of Shur. Shur can mean in Hebrew to travel or to sing, a connection to when this event immediately precedes the Song of the Sea, or the Song of Miriam. This may be an intended pun in Mosiah 18:30: “How blessed are they, for they shall sing to his praise forever.”

In both narratives, trees are instrumental in saving the people. Moses puts a tree into the waters, causing the waters to become drinkable. Likewise, the Nephites hide themselves in a grove of trees to escape death from King Noah’s armies.

One of the more significant similarities between our narratives is that at both the Waters of Mormon and the Waters of Marah, the people make covenants. Exodus 15:25 states that at the Waters of Marah, Moses “made for them a law and a judgement, and there he proved them.”

Last of all, there is yet another name pun between the two narratives. With one more in Exodus 15:27, immediately after leaving Marah, the Israelites come to a place called Elim. The name of the first person Alma baptizes is Helam. The similarity of these two names becomes even more apparent when one notes that in Mosiah chapter 27, the name was originally misspelled as Helim.

Alma’s People and the Israelites

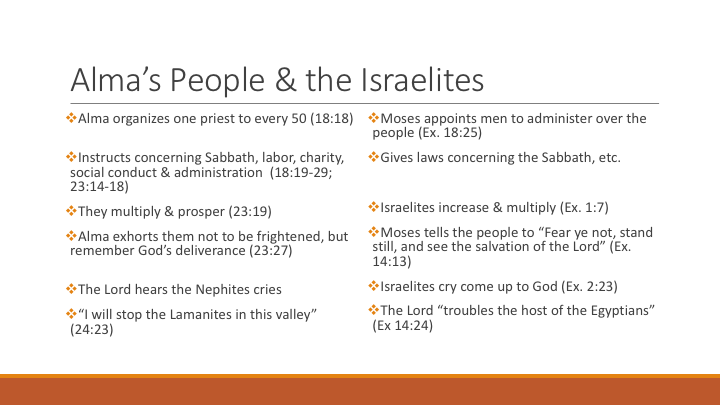

So as we read further on in Mosiah, we continue to see similarities between Alma’s people and the Israelites.

Alma organizes one priest to every 50 (18:18) and, likewise, Moses appoints men to administer over the people (Ex. 18:25).

Alma instructs concerning the Sabbath day, and labor and charity given to the poor, social conduct and administration for governing the people (18:19-29; 23:14-18), and as you know, Moses gives laws concerning all these aspects and much more.

And in chapter 23, it notes that Alma’s people multiply and prosper (23:19). Likewise, the Israelites increase and multiply (Ex. 1:7), and the pharaoh just doesn’t know what to do with them, those Israelites just keep on multiplying.

So Alma exhorts them not to be frightened, but to remember God’s deliverance (23:27) when the people see the Lamanites coming into the borders of their city. And when they’re about to cross the Red Sea, Moses tells the people to “Fear ye not, stand still, and see the salvation of the Lord” (Ex. 14:13).

When the Nephites are in bondage to the Lamanites, the text says that the Lord hears the Nephites’ cries. And when the Israelites are also in bondage to the Egyptians, it says in Exodus 2 that the cry comes up to the Lord (Ex. 2:23).

And lastly, the Lord tells Alma, “I will stop the Lamanites in this valley,” (24:23) when he tells them to keep going after they have fled the Lamanites. And while the Israelites are passing the Red Sea, the Lord says that he will “trouble the host of the Egyptians” (Ex. 14:24).

Richard Hay’s 7 Criteria for Intertextuality

In discussing the intentional use of the Exodus for these chapters in Mosiah, I would like to apply Richard Hay’s 7 Criteria for Intertextuality. So I will do a quick overview of that, just to see if yes, if this really was intentional.

- Availability: Was the proposed source of the allusion/echo available to the author of Mosiah? And, most likely, yes.

- Volume: What is the degree of explicit repetition of words or syntactical patterns?

We’ve seen there’s a fair amount of that in the text.

- Recurrence: How often does Mosiah elsewhere cite or allude to the same scriptural passage?

It definitely quotes a lot from the same chapters in Exodus that we have.

- Thematic Coherence: How well does the alleged echo fit into the line of argument that is developing in Mosiah?

There seems to be quite a unity of the Exodus theme through this story.

- Historical Plausibility: Could the author have intended the alleged meaning effect?

I’ll go into a little bit later why the author would want to include the Exodus.

- History of Interpretation: Have other readers, both critical and pre-critical, heard the same echoes?

I’m grateful to all the people, especially S. Kent Brown and [Charles D.] Tate who also helped me see that there are Exodus themes, and that really helped me, introduced me to the idea.

- Satisfaction: Does the proposed reading make sense?

I’ll leave that to you; I won’t tell you if it makes sense or not. That’s up to you.

Why the Exodus?

So if there really is intentional illusion and intertextuality between these two texts, what purpose does it have? Why use the Exodus story?

Obviously the Exodus is such an important part of the Israelites’ history. It’s the center of history of God’s covenant people. Also, I think the author wanted to show and exemplify the manifestation of deliverance, the eternal relationship between God and his covenant people.

I’d like to quote from James Plastaras in his book The God of Exodus, which says, “It was the Exodus which shaped all of Israel’s understanding of history. It was only in light of the Exodus that Israel was able to look back into the past and piece together her earlier history. It was also the Exodus which provided the prophets with the key to the understanding of Israel’s future. In this sense, the Exodus stands at the center of Israel’s history.”

Religious and Political Change

Also, the Exodus is such an important part of the Israelites’ history regarding religion and political change. In continuing on with this importance, we see that during the dedication of the temple in Jerusalem, the Temple of Solomon, it dates Exodus 480 years to the time of the Temple of Solomon (12×40 – the number of perfection). So they might have been using this is a way to say, see, this is kind of the center of the Exodus, and this is a legitimate new innovation for the people of Israel.

Likewise, in the Mosiah narrative, there is a major shift religiously and politically at this time. Mosiah 25: “king Mosiah granted unto Alma that he might establish churches throughout all the land of Zarahemla; and gave him power to ordain priests and teachers over every church” (Mosiah 25:19). So perhaps the author of Mosiah felt the need to show the validity of these new changes in light of the Exodus, showing that yes, these things have authority. And also, perhaps even later on, when King Mosiah makes the changes to have the judges rule instead of just one king.

Moses, Abinadi, and Christ

Lastly, we know that the Book of Mormon is another testament of Jesus Christ, and I believe that the most important reason the Exodus narrative was incorporated was to teach of Christ.

The Exodus and Moses were seen as types and shadows of Christ. Abinadi declared, “But behold, I say unto you, that all these things were types of things to come” (Mosiah 13:31). And even Jesus told the Nephites, “Behold, I am he of whom Moses spake, saying: A prophet shall the Lord your God raise up unto you of your brethren, like unto me” (3 Nephi 20:23).

In conclusion, I would like to end with a quote from S. Kent Brown, who puts it very eloquently. He says, “All of the words describing Israel’s bondage derive from the root ‘bd. It is also a noun from this same root which is translated “servant” in Isaiah 53, which Abinadi had quoted at length and then immediately linked to Jesus’ ministry. What is clear here is that Jesus is the expected servant (‘ebed) who, by paying the price of redemption, frees all those who will follow him from bondage (‘ab?d?h), the very term used in the Exodus account” (S. Kent Brown, “The Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon [Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998], 75–98).

I hope that this presentation was enlightening and will encourage you to look through this again and see how it testifies of Christ and the deliverance of God’s covenant people. Thank you very much.

More Come, Follow Me resources here.

Sara Riley graduated cum laude with a BA in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from BYU, and is currently working as a web designer part-time. She has published work on women hand drummers in ancient Israel and is interested in using technology to help spread Book of Mormon scholarship. At the moment, she continues to apply her knowledge of the ancient world to the Book of Mormon, all the while chasing around her toddler.

Sara Riley graduated cum laude with a BA in Ancient Near Eastern Studies from BYU, and is currently working as a web designer part-time. She has published work on women hand drummers in ancient Israel and is interested in using technology to help spread Book of Mormon scholarship. At the moment, she continues to apply her knowledge of the ancient world to the Book of Mormon, all the while chasing around her toddler.

The post Come, Follow Me Week 15 – Exodus 14–17 appeared first on FAIR.

Continue reading at the original source →