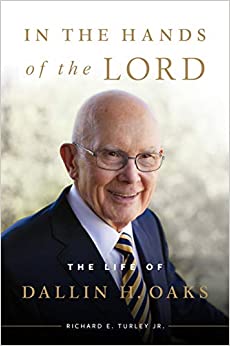

This biography of Dallin H. Oaks was written by Richard E. Turley, Jr., who has been associated with Oaks throughout most of his (Turley’s) professional life. Turley has served as the Director of the Church History Department (originally selected to work for the department by Oaks), Assistant Church Historian, and Director of Public Affairs. He has previously written or co-written several other books, including Victims: The LDS Church and the Mark Hoffman Case and Massacre at Mountain Meadows: An American Tragedy.

Dallin Harris Oaks was born August 12, 1932 in Provo, Utah. He got his middle name from his mom’s side of the family, who was descended from a brother of Martin Harris. He grew up in Provo; Twin Falls, Idaho; Payson (where he stayed with his grandparents at times due to the death of his father when he was 7); and Vernal. He came close to dying several times in his childhood, beginning with his birth, with miraculous preservation of his life occurring each time.

Oaks eventually made it to Brigham Young University, where he met his first wife, June Dixon, and married her in his junior year. He was in the Utah National Guard, and the Korean War was going on, so he was unable to serve a mission. After BYU, he graduated cum laude from the University of Chicago Law School, worked as a clerk for the Supreme Court, and then began working at a law practice. During this time he also served as a stake missionary.

He then returned to the University of Chicago Law School as a professor (also serving in the stake presidency) until he was chosen to be the president of Brigham Young University. From there he went on to become a justice of the Utah Supreme Court. He was a potential candidate twice for the United States Supreme Court, but both times felt it wasn’t right. When asked about it once, he said: “That job is like being called to be a General Authority. Only a fool would aspire to it, but no one would turn it down” (page 168).

In 1984 he received a surprise phone call from President Gordon B. Hinckley of the First Presidency, and he was called as an apostle, which he found to be shocking. “‘I feel so unworthy and so unprepared for this sacred calling,’ he confessed, ‘Yet I do know that there is nothing I cannot do if I am worthy of the help of our Heavenly Father. My challenge is to be worthy and to be in tune’” (page 180).

During his time as an apostle, he had many assignments and took very seriously his role as a special witness of the name of Christ. He became known for his doctrinal addresses. “He felt the heavy responsibility of spiritually feeding those who came–or tuned in–to hear him, and he wanted to align his will with God’s in selecting, developing, and addressing topics of importance in advancing the Lord’s purposes” (page 322).

One of his talks that is among my favorites was “Healing the Sick,” given in the April 2010 General Conference. Oaks gained faith in the power of the priesthood early in his life. His father was a doctor and someone once “asked him if he was going to grow up to be a doctor like his father and heal people. ‘No,’ he answered. He was going to be a ‘high priest like my father and bless babies’” (page 7). Later, when he was ten years old, he had an experience that “has been a significant influence on my faith in the power of the priesthood” (page 15). When he was staying with his grandfather, his younger cousin fell unnoticed into an irrigation ditch and wasn’t found for 20 or 30 minutes. He had been floating facedown and was dead. His grandfather gave him a blessing and he was revived. “‘He suffered no after-effects, filling a mission to Australia, marrying a lovely girl, and living an exemplary life as a Latter-day Saint husband and father. I am witness,’ Dallin concluded, ‘to the miracle of his childhood death and restoration’” (page 17).

One of his assignments was with Public Affairs, and this was when the Mark Hofmann case occurred. He was involved in responding to the media and encouraged transparency from the First Presidency in their dealings with Hofmann. After Hofmann was arrested and pleaded guilty, he wrote: “The outcome vindicates the Church in every particular! How blessed are we! The Lord truly looks after His work and His servants. We are buffeted by the world and afflicted with the consequences of our own mistakes, but when the stakes are large and the survival or significant momentum of the work is on the line, we are saved as by a miracle” (page 208). When later reviewing the manuscript of Turley’s Victims, he wrote: “The facts are there, and his effort will set the record straight for purposes of history. Those who want to believe the worst about the Church and its leaders will do so, but those who want the truth and have ears to hear and hearts to understand will at last have the complete facts on the Church…involvement in the Hofmann affair” (page 209).

There were many travel assignments, including time spent as the Philippines Area President. As he got older, this became harder, and in 2006 during a trip to Africa, he wrote: “As I reflect on what I have been doing on this trip…I have been impressed with the fact that I am working so hard that I would not possibly do this for money. I love doing this for the Lord, and I love the people with whom I work and those I meet on these trips” (page 292).

The book gives us some information about the creation of “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” and Oaks’ role:

During the fall of 1994, at the urging of its Acting President, Boyd K. Packer, the Quorum of the Twelve discussed the need for a scripture-based proclamation to set forth the Church’s doctrinal position on the family. A committee consisting of Elders Faust, Nelson, and Oaks was assigned to prepare a draft. Their work, for which Elder Nelson was the principal draftsman, was completed over the Christmas holidays. After being approved by the Quorum of the Twelve, the draft was submitted to the First Presidency on January 9, 1995, and warmly received.

Over the next several months, the First Presidency took the proposed proclamation under advisement and made needed amendments. Then on September 23, 1995, in the general Relief Society meeting held in the Salt Lake Tabernacle and broadcast throughout the world, Church President Gordon B. Hinckley read “The Family: A Proclamation to the World” publicly for the first time.

During the period that the proclamation was being drafted, Church leaders grew concerned about efforts to legalize same-sex marriage in the state of Hawaii. As that movement gained momentum, a group of Church authorities and Latter-day Saint legal scholars, including Elder Oaks, recommended that the Church oppose the Hawaii efforts…. (Page 215.)

There has been a theory that the Proclamation began as a response to the legalization efforts in Hawaii, and was written by a team of lawyers, but this clearly shows that not to be the case. If it sounds like it might have been written by legal experts, it’s probably because two of its co-writers were Oaks (a former Utah Supreme Court Justice) and Faust (a former lawyer).

After his wife, June, died in 1998, he had an experience in the temple where he felt her presence and heard her voice in his mind. She told him “(1) she is busy and happy, and (2) she knows why she died at this time. I was comforted.” Four months after she had died, he was in the temple again. This time he didn’t feel her presence, but “I did feel a thought she had left for me, somewhat like a written message: ‘Your needs are not so great now, so I will not visit you on a regular basis, but from time to time as you need.’…Elder Oaks wrote that he ‘went away strengthened for a new era in my life’” (pages 235-236). After that, he began thinking of remarriage and received advice and help from Elder L. Tom Perry, who introduced him to Kristen McMain. After a brief courtship and with the consent of his children, they were married.

As an apostle, Oaks responded to many letters. There are portions of some of his responses in the book, and here are some excerpts from those that I found interesting:

On another occasion…Elder Oaks offered four suggestions. The first was about reading from varied sources in searching for truth. Sometimes, Elder Oaks observed, those who say they read broadly exclude reading sources “that will sustain and nourish faith.” Second, he explained, “while doubt can be a virtue when it moves people to seek knowledge, it is also an eternal principle that faith precedes the receipt of knowledge from above.” Third, knowing the Church is true does not require “the kind of transcendental experience the Prophet Joseph Smith had.” That knowledge can come from simply keeping the Lord’s commandments. Fourth, we must avoid judging godly things “according to what seems ‘godly’ according to our standards or culture or experience.” Instead, “we are to learn from Him, not teach Him or confine Him within our criteria.” Finally, Elder Oaks wrote, no one can pass the responsibility for personal conversion to another. “The whole case is in your hands…and its resolution is between you and your Heavenly Father.”

…To a man who wrote on reconciling science and religion, Elder Oaks responded, “Because our knowledge of the truths of the gospel is still evolving with continuing revelation, and because the ‘truths’ of science are also very dynamic, I am skeptical about bringing them together at present, though I know that they will each be gloriously consistent when all truths are known.”

A man wrote asking whether he should refrain from promoting new concepts that came to him about Christ’s Atonement. “The Lord has given us a prophet and his two counselors,” Elder Oaks replied, “and they are the ones to whom we look for ‘new concepts’ on our doctrine. The rest of us should refrain.”

…One correspondent was bothered that a family member talked openly about purported spiritual manifestations… “Have you noticed,” Elder Oaks asked in response, “that General Authorities, fifteen of whom are sustained as prophets, seers, and revelators, rarely speak about personal and sacred spiritual experiences?

“That cannot be a coincidence,” he taught. “It is also true that there are many miracles and sacred spiritual experiences among the Latter-day Saints, and we rarely hear of them across the pulpit or in classes. That cannot be a coincidence either.

“True,” Elder Oaks agreed, “some individuals speak of their personal and sacred spiritual experiences, but I have noticed that those individuals are cautioned not to do so, and if they persist, they are generally released from their Church positions or requested not to speak in Church meetings.

“What explains all of this?” Elder Oaks inquired of the writer. “A person has only to read the directions in the Doctrine and Covenants to see that the Lord has told us that our sacred experiences are personal and are not to be shown before the world.” He concluded, “If every person would be careful to limit the use of their spiritual experiences to their own personal benefit, instead of using them for other purposes, the adversary would have less occasion to mislead us by counterfeit spiritual experiences.” (Pages 336-341.)

In 2018, Elder Oaks became President Oaks as he was called to be a counselor in the First Presidency. At this time, I observed that there were some that felt that the counselor under President Monson that he was effectively replacing (Dieter F. Uchtdorf) was being demoted. However, when Uchtdorf “met with President Nelson, he recommended two other men to be counselors in the First Presidency. ‘Elder Oaks was one of my recommendations,’ he later explained. ‘Through the course of those interviews,’ President Nelson recounted, ‘it became very clear to me, as I prayed about it, that Dallin should be First Counselor because, upon my demise, he’s the next President of the Church. That’s the kindest thing I could do to the Church and for him…to give that exposure” (page 345).

As a member of the First Presidency, “My understanding of the power of the Atonement of Jesus Christ has increased enormously. As a judge, I applied mortal laws and penalties. In contrast, as I have reviewed the cases of persons who have sinned previously and now seek renewal in the Church, I have been awed by the love of God and His merciful forgiveness of those who repent and return to Him…. I have greatly increased in knowledge of and appreciation for the inspired service of the members of the Twelve, the Seventy, the Presiding Bishopric, our General Officers, and our local leaders…. I have grown in my testimony of the reality of revelation to our living prophet, President Russell M. Nelson” (page 368).

Describing the First Presidency meetings, he said they “continue to be very revelatory for all three of us: open discussion of different points of view followed by sweet coming together in unity” (page 356). On another occasion he wrote that “The Lord is in charge, and with His direction we can make big changes” (pages 358-359). Later he wrote, “President Nelson is receiving…inspiration, and it is always confirmed to President Eyring and me. Thrilling!” (page 359).

Speaking of the many changes that have been made by the First Presidency since it was formed, Oaks said to members in Arizona: “Change is almost always exciting… But as I have thought about the many recent changes in the Church, I have felt some caution. The changes we have experienced in our Church meetings and policies should help us, but by themselves they won’t get our members to where our Heavenly Father wants us to be. The changes that make a difference to our position on the covenant path are not changes in Church policies or practices, but the changes we make in our own desires and actions” (page 361).

The book goes through Oaks’ life chronologically until his calling as an apostle. At that point, it shifts into being arranged thematically, including a chapter devoted to his first wife, followed by a chapter about his courtship and marriage to his second wife. The last three chapters cover his calling to the First Presidency and events that have happened up until the publishing of the book, with a summary of the book in the final chapter. I would have preferred to have as much detail of his later life as there is of earlier parts of his life, but understand that many aspects of being an apostle and member of the First Presidency require confidentiality (and the author does explain this problem in the introduction). The details that we are given are extremely interesting. And I can see the value of arranging his apostolic ministry into themes, as many things would have been interwoven throughout multiple years otherwise.

I enjoyed this book so much that I gave a copy to my dad for his birthday. He read it and then bought a copy for his sister. President Oaks has truly lived a remarkable life, and it has inspired me to be a better person and increased my testimony of living prophets and apostles.

Trevor Holyoak is the Vice President of FAIR. He has been actively involved with FAIR for many years and received the John Taylor Defender of the Faith Award in 2014. He graduated magna cum laude from Weber State University with a BS in computer science and now works as a programmer and systems administrator. He is currently serving as a stake emergency preparedness director and in the leadership of the Utah Valley Amateur Radio Club. He and his wife have five children and live in Cedar Hills, Utah.

Trevor Holyoak is the Vice President of FAIR. He has been actively involved with FAIR for many years and received the John Taylor Defender of the Faith Award in 2014. He graduated magna cum laude from Weber State University with a BS in computer science and now works as a programmer and systems administrator. He is currently serving as a stake emergency preparedness director and in the leadership of the Utah Valley Amateur Radio Club. He and his wife have five children and live in Cedar Hills, Utah.

The post Book Review: “In the Hands of the Lord: The Life of Dallin H. Oaks” appeared first on FAIR.

Continue reading at the original source →