The Know

While teaching “the poor class of people” at the hill Onidah (Alma 32:2–4), Alma used a metaphor to help them learn how to cultivate strong and lasting faith: he compared the word of the Lord to a seed, planted in their hearts (Alma 32:28; cf. 33:23; 34:4). If it is a good seed, he explained, it would sprout and begin to grow. And if it is properly nourished “it will get root, and grow up, and bring forth fruit” (Alma 32:37) until it becomes a full-blown “tree springing up unto everlasting life” (Alma 32:41; 33:23).

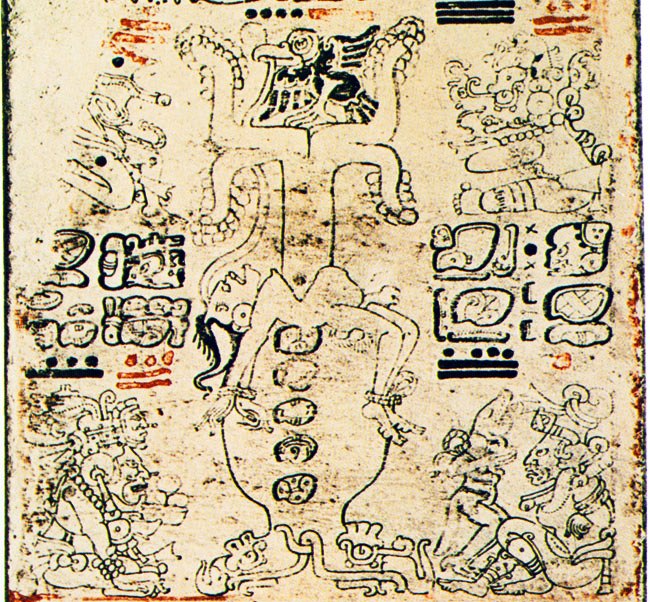

As Latter-day Saint scholar John L. Sorenson observed, “The Maya of the Classic period [ca. AD 250–900] may have preserved a visual correspondence to this concept,” through artwork depicting “trees growing from the breasts or hearts of sacrificial victims.”1 For example, the Dresden Codex (one of only four pre-Columbian Maya codices), “shows a sacrificial victim with a tree growing from his heart,” that Latter-day Saint archaeologist John E. Clark described as “a literal portrayal of the metaphor preached in Alma, chapter 32.”2 Similarly, Piedras Negras Stela 11 shows “a seedling grow[ing] from the heart of a sacrificial victim.”3 Sorenson described this as a potentially “distorted version of the Book of Mormon image of the gospel seed sprouting from the human heart.”4

Anthropomorphic Tree from Dresden Codex 3

Piedras Negras Stela 11. Drawing by Linda Schele.

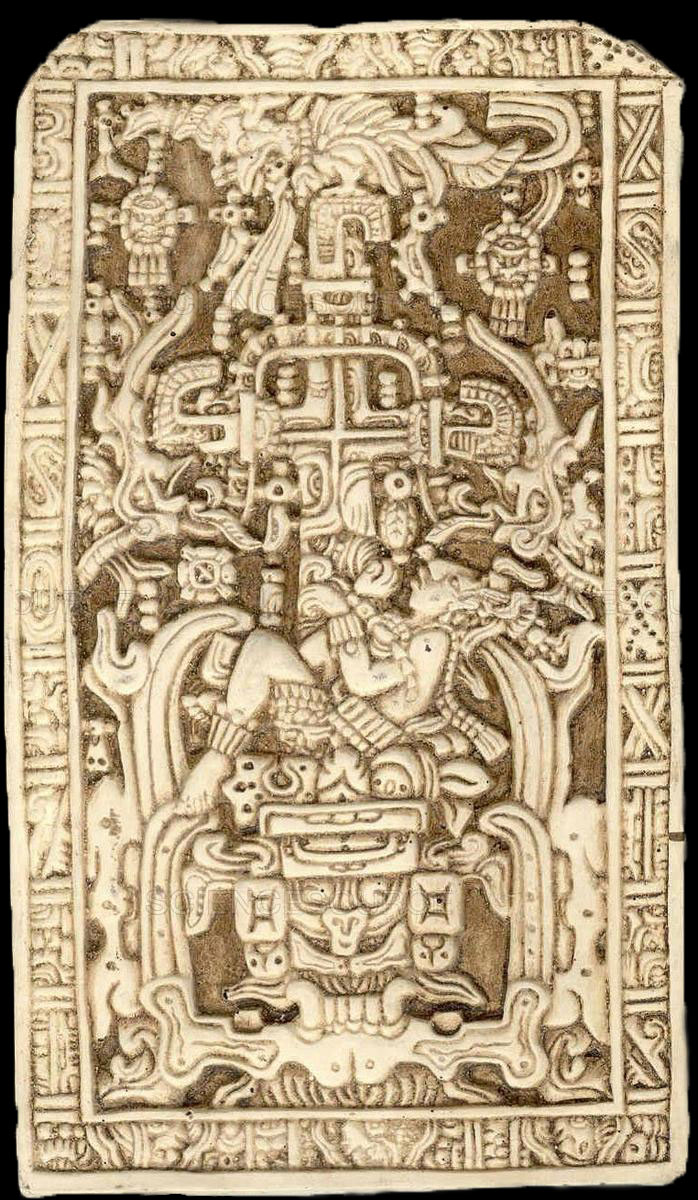

On the lid of Pakal’s tomb at Palenque, Pakal is portrayed as the sacrificed Maize God, and “from his body rises the World Tree, the earth’s central axis.”5 Joseph L. and Blake J. Allen believed “the carving has the appearance of a tree of life sprouting from the heart of the king, which is reminiscent of Alma’s discourse on planting the seed of faith in our hearts and nurturing it to become a tree.”6 In addition, seven of Pakal’s ancestors are depicted as fruit-bearing trees along the sides of his sarcophagus lid,7 reinforcing the idea that he, like his ancestors, would rise from the dead as an “anthropomorphic tree.”8

The world tree arising from the body of the sacrificed maize god. Sarcophagus lid of the Tomb of Pakal, 7th century, Palenque. Image via New York Public Library, sciencesource.com.

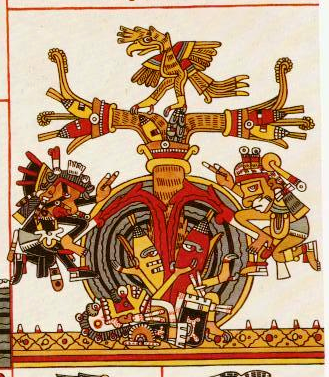

In a codex from Central Mexico, each of the five directional trees (for the four cardinal directions, plus a central tree) is depicted as growing out of the bodies of a sacrificed earth goddess.9 These images appear to be related in some way to that found on Pakal’s tomb, thus suggesting that this was a pan-Mesoamerican concept.10

Tree Growing from Skeletal Figure Codex Borgia 53

The Why

Alma’s metaphor would have naturally resonated with peasant farmers of a predominately agricultural society, much like the Savior’s Parable of the Sower was relatable to his audience of laborers and agriculturalists in Palestine (Matthew 13:1–23; Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:4–15).11 Yet the imagery reviewed here suggests that there were additional factors that made this metaphor meaningful within the possible cultural backdrop of Book of Mormon peoples.12

Reap Your Reward by Courtney von Savoye, depicting the fruits of Alma 32. First Place winner of the 2018 Book of Mormon Central Art Contest.

As Sorenson reasonably concluded, “When Alma taught the Zoramites a lesson in faith referring to the tree of life sprouting from the heart (Alma 32:28–43), he was using Mesoamerican religious imagery.”13 Kirk Magleby likewise reasoned, “Alma may have been alluding to an existing Mesoamerican cultural idea, painting a mental image that his Zoramite hearers in Antionum would have understood.”14 And indeed, that image was used in those surrounding cultures to portray the rising of a royal being unto an eternal glorified life, and Alma wanted to assure his listeners that the seed of belief in the power of resurrection through the Son of God would grow up in them, as ordinary people, to yield the fruits of eternal life.

Moreover, in ancient Mesoamerica, the World Tree (or Tree of Life) held the order of the cosmos together. Through ritual actions and sacrifices, rulers would become the personification of the World Tree and perform rites that restored and maintained cosmic order and balance.15 As Elizabeth A. Newsome explained, “kings assumed the role of this nurturing plant in their sacrificial rites, thus becoming a source of spiritual power, abundance, and everlasting life.”16

Within such a cultural background, being shut out of the sacred worship spaces (see Alma 32:5) and thus being unable to witness and participate in such rites would have constituted a significant spiritual crisis for these poor and humble Zoramites. Alma built upon this circumstance, teaching his audience that they could, in fact, still worship the true Son of God outside their synagogues: they could pray in their own homes and in their own hearts, and that by doing so, they could personally have that “tree springing up unto everlasting life” within themselves (Alma 32:41; 33:23).

Assuming Alma was drawing upon this conceptual world, doing so likely maximized the impact and effectiveness of his teachings to these poor and humble Zoramites, directly addressing the pressing and urgent spiritual crisis they felt by being shut out of their synagogues and worship services (Alma 32:5). He thus demonstrated his sensitivity to his audience’s needs to hear the gospel taught “according to their language, unto their understanding” (2 Nephi 31:3; Doctrine and Covenants 1:24), a concept that goes beyond mere language and words and extends to the various cultural backgrounds, life experiences, and historical settings of God’s children, both past and present.17

Further Reading

Kirk Magleby, “Anthropomorphic Trees,” Book of Mormon Resources (blog), February 3, 2016 (updated July 6, 2020).

Allen J. Christenson, “The World Tree and Maya Theology,” in The Tree of Life: From Eden to Eternity, ed. John W. Welch and Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011), 151–170.

John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 182–183, 208.

- 1. John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 465. For a more recent edition of the source Sorenson cites here, see Robert J. Sharer with Loa P. Traxler, The Ancient Maya, 6th ed. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006), 724. According to Patrizia Granziera, “Concept of the Garden in Pre-Hispanic Mexico,” Garden History 29, no. 2 (2001): 193, the sacred tree growing out of a sacrificial victim is one of four standard depictions, the others being depictions of it growing out of a monster mask, the jaws of the earth monster, and the crouching earth deity.

- 2. John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Relief,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2005): 46.

- 3. Kirk Magleby, “Anthropomorphic Trees,” Book of Mormon Resources (blog), February 3, 2016 (updated July 6, 2020). Sharer and Traxler, Ancient Maya, 724 also show a similar scene from Piedras Negras Stela 14.

- 4. John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 208.

- 5. Mary Ellen Miller and Megan E. O’Neil, Maya Art and Architecture, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2014), 137, capitalization silently altered. Diane E. Wirth, Parallels: Mesoamerican and Ancient Middle Eastern Traditions (St. George, UT: Stonecliff Publishing, 2003), 111 similarly said “from his body springs the Tree of Life—the World Tree” while describing the same scene. Simon Martin, “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and other Tales from the Underworld,” in Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, ed. Cameron L. McNeil (Gainsville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2006), 160, which describes the scene as Pakal’s “transformation into an ascending World Tree.”

- 6. Joseph L. Allen and Blake J. Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, rev. ed. (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2011), 337, fig. 15-1, capitalization silently altered.

- 7. See David Stuart and George Stuart, Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2008), 117, 138–139, 145, 149.

- 8. Stuart and Stuart, Palenque, 173–177 discusses the scene on Pakal’s sarcophagus lid as a resurrection scene invoking both solar and tree/maize imagery to express newness of life. On anthropomorphic trees, see Magleby, “Anthropomorphic Trees”; Simon Martin, catalogue entry for plate 9, in Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks: Pre-Columbian Art at Dumbarton Oaks, no. 4, ed. Joanne Pillsbury, Miriam Doutriaux, Reiko Ishihara-Brito, and Alexander Tokovinine (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, 2012), 109–119.

- 9. See Gisele Diaz and Alan Rodgers, eds., The Codex Borgia: A Full-Color Restoration of the Ancient Mexican Manuscript (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1993), plates 49–53. See also Granziera, “Concept of the Garden,” 193.

- 10. Martin, “Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion,” 160–161 highlights the similarities between these scenes and that found on Pakal’s tomb lid.

- 11. See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:457.

- 12. As apostate Nephites, the Zoramites may have been more strongly influenced by the surrounding ancient American cultures. See Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 25–55.

- 13. John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1985), 219.

- 14. Magleby, “Anthropomorphic Trees.”

- 15. See Allen J. Christenson, “The World Tree and Maya Theology,” in The Tree of Life: From Eden to Eternity, ed. John W. Welch and Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2011), 151–170.

- 16. Elizabeth A. Newsome, Trees of Paradise and Pillars of the World (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2001), 26.

- 17. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Lord Speak to Men ‘According to Their Language’? (2 Nephi 31:3),” KnoWhy 258 (January 6, 2017). See also Mark Alan Wright, “‘According to Their Language, unto Their Understanding’: The Cultural Context of Hierophanies and Theophanies in Latter-day Saint Canon,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 51–65.

Continue reading at the original source →