Last weekend, the Emancipation Memorial in Washington D.C. became the latest flashpoint in the emotionally charged and culturally sensitive debate over public statues. Historically significant as perhaps the only monument in the Capitol paid for entirely by emancipated slaves (mostly Union veterans), the bronze statue depicts Abraham Lincoln standing erect with a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation and extending a beneficent hand to a kneeling slave amidst broken shackles.

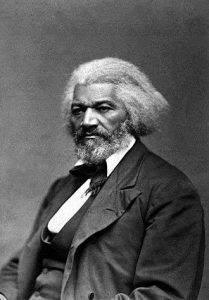

Regrettably, the former slaves who paid for the memorial were not consulted in the design. Even in its day, the statue’s contrast of postures attracted criticisms from prominent African Americans like Frederick Douglass, who thought “a more manly attitude” for the slave “would have been indicative of freedom” and of the role African Americans had in securing their liberties. The same criticisms persist today, recently inflamed with reminders of racial injustices.

Mostly obscured in this debate, however, are the conclusions of Lincoln and Douglass regarding due credit for the emancipation of America’s enslaved population. Some commentators, critical of the statue, have cited Lincoln’s appeal to an elderly former slave—“Don’t kneel to me, that’s not right”—while omitting the other half of Lincoln’s kindly interaction—“You must kneel to God only and thank Him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.”

The story of the remainder of Lincoln’s words begins 400 years ago, with this July 4th straddling two momentous anniversaries in American history. Last August marked the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves sold in the American colonies, approximately twenty Angolans kidnapped by Portuguese traders and sold by Dutch sailors to the colonists of Jamestown, Virginia. And this November marks the 400th anniversary of the first document establishing self-government in the American colonies, the signing of the Mayflower Compact upon the arrival of the Pilgrims to the New World.

The United States Constitution has guaranteed essential freedoms and provided the framework for peaceful, democratic government for nearly 250 years.

It would take hundreds of years, a terrible Civil War, and a trying Civil Rights Movement before the blessings of self-government would be extended to the descendants of African slaves carried in bonds to America’s shores. Yet the history of that Providential deliverance and of the mending, at least partially, of America’s deepest racial wounds can inspire us today as we continue to grapple with the residual effects of such terribly racist legacies.

The first written constitution in the world, the United States Constitution has guaranteed essential freedoms and provided the framework for peaceful, democratic government for nearly 250 years. It has also influenced the constitution of every other nation in the world. Tragically, for all its virtues, it was conceived only as a result of an agonizing concession that permitted and even enforced the evil of slavery in the nascent Republic. Nevertheless, if the Constitution’s original sin was slavery, its bedrock virtue of self-government, guided by a Divine Providence, eventually purged the monstrous injustice of human bondage, though not until the nation had atoned for its ravages through its own Civil War.

Speaking at the Constitutional Convention, George Mason foresaw the national calamities that must unavoidably befall the nation if it were to countenance slavery. “As nations can not be rewarded or punished in the next world they must be in this. By an inevitable chain of causes & effects providence punishes national sins, by national calamities.” Decades later, that prescient warning was realized in the nation’s tragic descent into secession and war. Convinced that the recently elected Abraham Lincoln and his “Black” Republican Party would infringe their constitutional rights, Southern aristocratic elites rebelled against democratic government after losing the presidential election. Ironically, in waging war, they sowed the very seeds from which the end of slavery would eventually be reaped.

Slavery’s constitutional protections could not be interrupted in peace, but the Confederacy’s initiation of war set in motion a series of events that brought about the demise of the so-called “peculiar institution.” As the North desperately sought an alternative to the conflict, Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave and powerful anti-slavery orator, was distraught when Lincoln, in his First Inaugural Address, promised not to interfere with slavery in the States where it then existed. Douglass foresaw that slavery would forever foment disunion and that there would be no peace and no union with slavery intact. “Whatever a man soweth,” he warned, “that shall he reap.” Though bitterly disappointed and on the verge of emigrating from his homeland, Douglass nevertheless sensed something changing—“There is a general feeling amongst us, that the control of events has been taken out of our hands, that we have fallen into the mighty current of eternal principles—invisible forces—which are shaping and fashioning events as they wish, using us only as instruments to work out their own results in our national destiny.”

Those “invisible forces” worked upon the people of the North, including Abraham Lincoln, to consider what had hitherto been unthinkable—the immediate emancipation of millions of men, women, and children held as slaves. Lincoln had always “hated” slavery, but he did not believe the President had the constitutional authority to enact his own moral judgment and abolish it. As the war continued, however, Lincoln came to see the abolition of slavery as a “military necessity,” justifiable under the War Powers granted to the President as Commander in Chief. After making a “covenant with God” that he would issue the Emancipation Proclamation if the Union armies were victorious at the fateful Battle of Antietam, Lincoln made good on his promise to his “Maker” and signed the proclamation as a war measure.

In reflecting a year later upon his momentous decision, Lincoln explained to a group of Border State politicians,

“I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Wither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God.”

Lincoln later refined those sentiments in his Second Inaugural Address, describing the nation’s Civil War as a type of national atonement for its collective sin of slavery. After a gloomy, overcast morning, the sun began to shine as Lincoln delivered perhaps the most scripturally inspired presidential address in American history—

“‘Woe unto the world because of offences! for it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!’ If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him. Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”

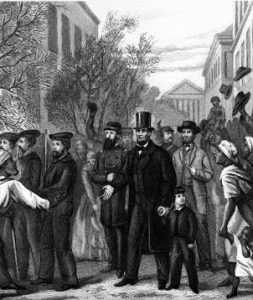

Among those gathered in the crowd was Frederick Douglass. He resolved to attend the inaugural reception and see Lincoln personally that evening at the White House, the first person of color ever to do so. He would be turned away, even tricked to leave through a passageway. But he knew Lincoln would not have wanted it so and called out for help. When at last admitted, Lincoln saw him and said loud enough for those near to hear, “Here comes my friend Douglass.” The President pressed him to know his thoughts about the speech, even insisting, “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.” Douglass replied, “Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort.”

“You must kneel to God only and thank Him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.”

Within weeks, Union armies had driven the Confederacy from its capital in Richmond, mere days from surrender at Appomattox and the effective end of the war. Lincoln desired to see Richmond. With only a small escort of Union troops, he walked the streets of the abandoned Confederate capital, amidst ecstatic celebrations of Richmond’s liberated slave population. When an elderly former slave recognized Lincoln, he knelt down. “Don’t kneel to me,” Lincoln kindly told him, “that is not right.” Then, humbly acknowledging the Divine source of emancipation, Lincoln gently counseled, “You must kneel to God only and thank Him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy.”

As we continue to grapple with the dedication of our public spaces to the nation’s historic events and civic heroes, may we not lose sight of the noblest virtue in commemorating our Republic’s history—the witness of a Divine Providence bestowing the blessings of liberty upon the diverse children of the same, loving God.

The post “Thank Him for the liberty you will hereafter enjoy” appeared first on Public Square Magazine.

Continue reading at the original source →