Some valuable information may be related to the order of the "Egyptian" words and their definitions in the GAEL. In my last post, a reader who goes by "Joe Peaceman" made a valuable point as he tried to explore what the text of the GAEL tells us about its construction. He pointed to an interesting correction that W.W. Phelps made throughout the various "degrees" of his document. The word "Beth-ka" had apparently been skipped early in his work, and so Phelps added a note on blank page calling for its insertion between two other characters. The word "Beth-ka" or "Bethka" or "Beth ka" in GAEL is variously said to mean "the greatest place of happiness" (GAEL, p. 2), "a more complete enjoyment— a more beautiful place" (p. 8), "a place of exceeding great beauty" (p. 12), "a larger garden— more spacious plain" (p. 17), "A large garden, a large val[l]ey or a large plain" (p. 19), and "Another & larger place of residence made so by appointment. by extension of power; more pleasing, more beautiful: a place of more complete happiness, peace and rest for man" (p. 34).

We can see the Phelps' work of inserting "Bethka" in several parts of his document, including:

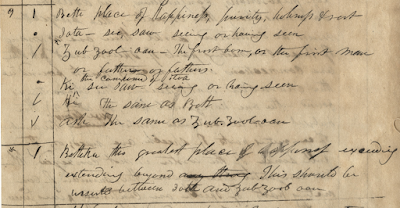

- Page 2, where it is inserted between bars low on the page, with a note that it should be inserted above. See Figure 1 below.

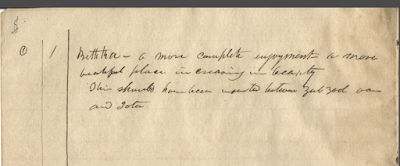

- Page 8, where it is the sole entry on what was one of the many blank pages left in the GAEL, with a note that it should be inserted on the opposing page. See Figure 2.

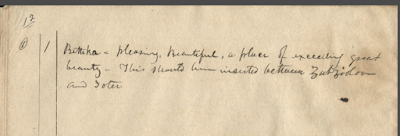

- Page 12, which, as with page 8, is inserted on a blank page. See Figure 3.

- Page 17, which has "Bethka" at the top of the page with a note that it should have been inserted between "Iota" and "Zub Zoal oan" on the previous page, page 16. The page is then filled with additional words and definitions.

- Page 19, which has "Beth ka" at the top of a blank page and a note that it should "have been inserted between Iota and Zub Zaol aon on the opposite page," page 20.

|

| Fig. 1. "Bethka" added out of sequence on page 2 of the GAEL. |

|

| Fig. 2. "Bethka" inserted on a blank page, page 8 of the GAEL. |

|

| Fig. 3. "Bethka" inserted on a blank page, page 12 of the GAEL. |

In creating a dictionary or an "alphabet" of a foreign language, what is the importance of word order? If one is creating a versatile tool for translating texts, the order should enable one to easily look up a word to find its meaning. In Chinese-English dictionaries, for example, Chinese words can be arranged based upon alphabetic order of the transliteration, or based on characteristics of the characters (governing portions called "radicals" or number of strokes) that can make it easy ("easy" compared to having no order -- it still can be difficult) to find a word. Lists of words for language study can be grouped in other ways as well (common verbs, common nouns, etc.). But what is it about "Bethka" that requires it to be inserted not next to "Beth" but between "Iota" and "Zub Zoal oan"? Why would Phelps care about precise word order here when the words aren't being arranged alphabetically or based on common meaning, sound, or structure of the "Egyptian" character (

Reader "Joe Peaceman" provides the most plausible answer, I think. He notes that in the sequence of words into which "Bethka" needs to be inserted in a particular place, the word order links them to the text of Abraham 1:1-2. Below is part of Abraham 1:1-2, where we have these phrases, in order, and their relationship to words in the GAEL in brackets:

1 ... at the residence of my fathers [1. "Beth" - described as a place or residence]Phelps cared about the order and felt a need to insert "Bethka" throughout his document in a place that would make it line up with something. Line up with what? Why do that unless he was trying to use the existing text of the Book of Abraham translation as some kind of a tool, perhaps Kirtland's answer to the Rosetta Stone, perhaps being used to attempt the very kind of thing that Champollion was trying to do, namely, to create an "Alphabet" (that's a term that was frequently used in the press of that era to describe Champollion's work) to crack the mysterious Egyptian language? As "Joe Peaceman" puts it, "This is obviously aligned to Abraham 1, and it appears that Phelps saw the order that the cosmic journey/drama was about to play out in Abraham's life. How did he know without a text?"

I, Abraham, saw [2. "Iota" - see, saw, seeing, or having seen]

that it was needful for me to obtain another place of residence; [3. "Bethka" fits here, referring to a better place and, on p. 34, "Another & larger place of residence"]

2 And, finding there was greater happiness and peace and rest for me, I sought for the blessings of the fathers, [4. "Zub zool— oan"— which can mean "father or fathers"]

If Phelps were just guessing at the meaning of various symbols (most of which aren't even Egyptian) to make some kind of dictionary, the work he did to insert "Bethka" in five parts of his document in a specific place would make no sense. But if there were an existing story line in an existing text that he was working with, perhaps for some aspect of his "pure language" interest, then the bits and pieces of the GAEL that align with the Book of Abraham make more sense. The purpose of the GAEL is still unclear, but what should be clear is that Phelps began this project in the GAEL with at least some and perhaps much of the Book of Abraham before him. Contrary to the assertions of some critics, the GAEL is more likely to be drawing upon the Book of Abraham rather than the other way around.

Similar conclusions can be reached by examining the cosmological material in the GAEL, such as that on pp. 33-34, the last pages with definitions. There and elsewhere one finds Kolob, governing planets, cubits, earth, moon, sun, and related cosmological references. It's plausible and logical that Facsimile 2 and Abraham 3 had already been translated when the GAEL was being produced.

This topic also reminds us of the problem when some of our own scholars who insist that the Book of Abraham was largely the fruit of nineteenth-century Egyptomania without knowledge of one of the main aspects of Egyptomania: fascination with the news of Champollion and the Rosetta Stone. If Phelps and the early Saints were unaware of those widely known stories where much was said about the "alphabet" being prepared by Champollion based on the translation he had on the Rosetta Stone, and if they had no clue about the phonetic aspects of the Egyptian language revealed in that work, why would Phelps and his peers strive to also create an "alphabet" of the Egyptian language? But if they were creating an "alphabet," it stands to reason that they would start with a known translation and use it to try to decode the language, Champollion-style. They messed up terribly, of course, and raise numerous questions in the process, such as why they are using many characters that aren't even Egyptian. That fact raises doubt about the project really being related to deciphering Egyptian. Perhaps they were trying to create their own "pure language" guide (where "Egyptian" is code for "pure language"), or perhaps there is something to William Schryver's theory of making a reverse cipher, or perhaps there is something even stranger going on.

With many key documents clearly being missing and so many puzzles in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, it's hard to determine what they were trying to do. But there is evidence that helps us understand when they were trying to do it, and that seems to be after at least some of the revealed translation had been given. It's more logical to see the GAEL as dependent on the translated text, not as a source that was used to create it.

Update, July 20, 2019: An important indication of the importance of word order to W.W. Phelps for a portion at least of his Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language (GAEL) was mentioned by Joe Peaceman that I wish to emphasize here. At the top of page 16 of the GAEL is this statement from Phelps: "This order should be preserved according to the signification of the degrees." Then follows the list of some key "Egyptian" words related to Abraham 1: Beth, Iota, Zub Zaol=oan, etc., with a note on the next page about the need to insert Bethka between Iota and Zub Zaol=oan.

Joe Peaceman, speaking to Dan Vogel, then says:

We agree that the BofA wasn’t translated from the GAEL but, the precision of alignment logically indicates that, when they created the GAEL, it was either created "to" the BofA or the BofA was created to it.This is an important issue. Was the GAEL based on, or created "according to" an existing Book of Abraham, or was the Book of Abraham created based on, or "according to" the GAEL? If the GAEL was Joseph's "inspired" tool to create the Book of Abraham, it or some other "alphabet" could come first, and then the Book of Abraham translation would be conducted somehow. The opposite scenario is that the GAEL was derived from the Book of Abraham, perhaps as an intellectual tool to understand Egyptian or as a tool to create some kind of writing system related to the "pure language" (the hypothesized Adamic language) that interested W.W. Phelps and Joseph.

Joe Peaceman astutely argues that if the GAEL came first, then the Book of Abraham should conform to it. But the recognition that something had been skipped or was in the wrong order in the GAEL seems to suggest that there was an outside control forcing that change, and that control would naturally be the dictated and revealed text of the Book of Abraham. The need for a particular order was important enough that the correction was made in multiple places of the GAEL after the initial list of these characters had been written down and copied several times without "Bethka" in the right place. So what the GAEL made based on the Book of Abraham or vice versa?

Joe Peaceman picks up on a subtle word choice in Joseph Smith's History from July 1835, p. 597. Here is the transcript from the Joseph Smith Papers Project website:

July 1835 <Translating the Book of Abraham &c.> The remainder of this month, I was continually engaged in translating an alphabet to the Book of Abraham, and arrangeing a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients. [emphasis added]It does not say that they were preparing the alphabet based on or for the Joseph Smith Papyri, but "to" the Book of Abraham, as if that came first. You can argue that the use of "to" is casual and ambiguous, but it still creates the logical though debatable presumption that the Book of Abraham is controlling the creation of the GAEL and not the other way around. It's not absolute proof, but it certainly must be considered as possible evidence, contrary to those who declare that there is absolutely no evidence that an existing translation came before the GAEL and the Egyptian Alphabet documents.

If Joseph were using the GAEL as an inspired tool to create the translation and left out the phrase related to Bethka, the reasonable next step would be to correct the dictated text rather than to rework the GAEL. The choice to rework the GAEL (in five places) points to the existing translation as the controlling source, IMO. Given the primacy of a divinely translated text, it is natural that the GAEL would be reworked if this were a secondary document, part of an exercise from one or more of Joseph's scribes (with Joseph's support, of course) using the translation as a key. The subsequent intellectual exercise was a failure, but that tells us nothing about the value of the initial divine translation.

You may also argue that the statement from July 1835 is referring to the papyrus manuscript Joseph thought contained the Book of Abraham, but that position raises two questions: (1) What apparently missing manuscript was Joseph translating? (2) Why do so many of the characters for which order matters appear to not only not be on the papyri, but appear to not even be Egyptian? This is based on examining the "Comparison of Characters" section of Volume 4 of the Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations series on the Book of Abraham, edited by Brian Hauglid and Robin Jensen (2018) and comparing the characters from the relevant portion of the GAEL. It seems that most or even all of these order-sensitive characters aren't on the papyri and might not even be Egyptian. So what's going on?

Here the "pure language" issue may be important. Since so much of the "Egyptian" in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers is not even Egyptian (e.g., in the Egyptian Counting document, not a single character is actual Egyptian), William Schryver has offered the reasonable argument that "Egyptian" may be a code word for "pure language" in the Kirtland Egyptian Papers. If the Saints involved in this effort were trying to create a "pure language" writing system or a "reverse cipher" (Schryver's preferred theory), then the characters would not need to be Egyptian. Many of the handful of characters on some Book of Abraham manuscripts are Egyptian and from one important papyrus, but as I recall only 3 of them have translations in the GAEL. It's all quite perplexing, but whatever those involved with the KEP were doing, the evidence points to the translation (at least of Abraham 1:1-2) coming first, before the GAEL was created. It simply was not meant to be the source for the Book of Abraham or a tool for its translation.

But some Egyptian characters are being matched from a papyrus to portions of the Book of Abraham in some manuscripts. Doesn't that prove that Joseph translated those characters to give the text? Recall that when Joseph translated the reformed Egyptian of the gold plates, he did not need to stare at specific plates to give the translation. The text flowed swiftly through revelation while the plates were not even opened up. Something similar may have happened with the Book of Abraham. We know there were other papyrus documents that were presumably burned in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Was the translated text of the Book of Abraham on them? Or on none of papyri? I favor versions of the missing scroll theory, but it's not the only plausible approach.

If Joseph had been able to keep the gold plates, Joseph and the scribes might be tempted to try to crack reformed Egyptian by using the translation as a key, but they might not immediately know which characters of which plates correlate to specific portions of the text. If the scribes didn't know which papyrus documents, if any, were the source for the specific words of the translated text, they might have made reasonable guesses, or perhaps they turned to the papyrus that had some related figures on it and assumed it might have text or "mnemonic clues" related to the text from elsewhere. Clearly we don't know what they were thinking or doing, but their intellectual efforts in all aspects of the KEP may tell us very little about how Joseph did the translation if the translation came first through revelation, similar to how he translated the Book of Mormon, with relatively little dependence on the plates. I think there is significant evidence from multiple fronts that the translation predates the GAEL, the Egyptian Alphabet documents, and the three manuscripts of the Book of Abraham that have Egyptian characters (and some non-Egyptian characters) in their margins.

This post is part of a recent series on the Book of Abraham, inspired by a frustrating presentation from the Maxwell Institute. Here are the related posts:

- "Friendly Fire from BYU: Opening Old Book of Abraham Wounds Without the First Aid," March 14, 2019

- "My Uninspired "Translation" of the Missing Scroll/Script from the Hauglid-Jensen Presentation," March 19, 2019

- "Do the Kirtland Egyptian Papers Prove the Book of Abraham Was Translated from a Handful of Characters? See for Yourself!," April 7, 2019

- "Puzzling Content in the Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar," April 14, 2019

- "The Smoking Gun for Joseph's Translation of the Book of Abraham, or Copied Manuscripts from an Existing Translation?," April 14, 2019

- "My Hypothesis Overturned: What Typos May Tell Us About the Book of Abraham," April 16, 2019

- "The Pure Language Project," April 18, 2019

- "Did Joseph's Scribes Think He Translated Paragraphs of Text from a Single Egyptian Character? A View from W.W. Phelps," April 20, 2019

- "Wrong Again, In Part! How I Misunderstood the Plainly Visible Evidence on the W.W. Phelps Letter with Egyptian 'Translation'," April 22, 2019

- "Joseph Smith and Champollion: Could He Have Known of the Phonetic Nature of Egyptian Before He Began Translating the Book of Abraham?," April 27, 2019

- "Digging into the Phelps 'Translation' of Egyptian: Textual Evidence That Phelps Recognized That Three Lines of Egyptian Yielded About Four Lines of English," April 29, 2019

- "Two Important, Even Troubling, Clues About Dating from W.W. Phelps' Notebook with Egyptian "Translation"," April 29, 2019

- "Moses Stuart or Joshua Seixas? Exploring the Influence of Hebrew Study on the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language," May 9, 2019

- "Egyptomania and Ohio: Thoughts on a Lecture from Terryl Givens and a Questionable Statement in the Joseph Smith Papers, Vol. 4," May 13, 2019

- "More on the Impact of Hebrew Study on the Kirtland Egyptian Papers: Hurwitz and Some Curiousities in the GAEL," May 20, 2019

- "He Whose Name Cannot Be Spoken: Hugh Nibley," May 27, 2019

- "More Connections Between the Kirtland Egyptian Papers and Prior Documents," May 31, 2019

- "Update on Inspiration for W.W. Phelps' Use of an Archaic Hebrew Letter Beth for #2 in the Egyptian Counting Document," June 16, 2019

- "The New Hauglid and Jensen Podcast from the Maxwell Institute: A Window into the Personal Views of the Editors of the JSP Volume on the Book of Abraham," July 1, 2019

- "The Twin Book of Abraham Manuscripts: Do They Reflect Live Translation Produced by Joseph Smith, or Were They Copied From an Existing Document?," July 4, 2019

- "Kirtland's Rosetta Stone? The Importance of Word Order in the 'Egyptian' of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language," July 18, 2019

- "The Twin BOA Manuscripts: A Window into Creation of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language?," July 21, 2019

- "A Few Reasons Why Hugh Nibley Is Still Relevant for Book of Abraham Scholarship," July 25, 2019

Continue reading at the original source →