The Know

Riplakish, the tenth Jaredite king, was a vain and wicked ruler who “did erect him an exceedingly beautiful throne” (Ether 10:6).1 While it is difficult to determine the exact timing, it is safe to say that this story about an extravagant throne dates to very early on in pre-Columbian America.2 LDS archaeologist John E. Clark confirms that: “The earliest civilization in Mesoamerica is known for its elaborate stone thrones.”3

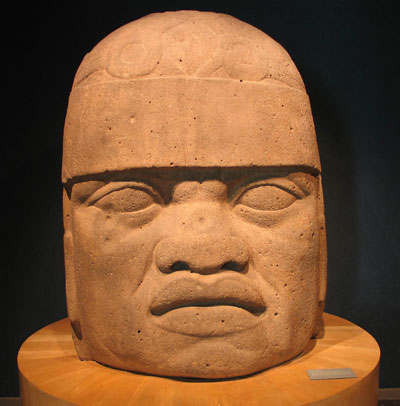

Known to scholars as the Olmec (ca. 1700–400 BC),4 the first Mesoamerican civilization began constructing thrones of stone between 1350–1000 BC.5 Such thrones were usually made out of a single, large, altar-like stone, ornamentally carved with three-dimensional depictions of the rulers themselves seated in cave-like openings.6

According to art historian Mary Ellen Miller, some thrones may have been painted or otherwise adorned in “brilliant colors.”7 One such depiction of an elaborate, multi-color throne appears in a wall painting from the late Middle Preclassic period (ca. 800–500 BC) at Oxtotitlan, Mexico that strongly resembles an Olmec throne from the site of La Venta (“Altar 4”).8

The massive stones used to make these thrones and the Olmec’s colossal stone heads could weigh up to 40 tons, and were transported from as far as 90 km (about 56 miles).9 “The sheer labor requirements involved in these operations,” explained Christopher A. Pool, “attest to the exceptional power of the rulers who commissioned them.”10

“The altar-throne was an integral part of the apparatus of Olmec rulers,” declared Richard Adams.11 Mary E. Pye explained that the thrones functioned “as markers in the social and political hierarchy.”12 According to James Porter, Olmec “thrones played a role in the careers of Olmec leaders commensurate with their impressive appearance as sculptures.”13

John E. Clark, writing with Arlene Colman, noted that construction of massive thrones was one of the ways Olmec kings memorialized themselves (along with colossal stone heads and full-figure statues).14 Olmec thrones served as “seats of power,” symbolically positioning rulers as seated between the human and divine realms,15 and legitimizing their high-status by establishing continuity back to founding ancestors.16 They also positioned “the ruler, both figuratively and contextually, in control of agricultural fertility,” where he could control “the arrival of the rains and, by extension, the continued agricultural bounty of the lands.”17

The Why

To construct an “exceedingly beautiful throne” required that Riplakish possess sufficient power to harness a massive labor force. Riplakish is depicted as the second king following a famine which had decimated the Jaredite kingdom (Ether 9:28–35).18 His father had begun to rebuild the kingdom (Ether 10:1–4), and by the time Riplakish took over the kingdom he wielded considerable power. He burdened the people with burdens “grievous to be borne” and forced them to “labor continually” (Ether 10:5–6).

In constructing an elaborate throne, Kerry Hull proposed that Riplackish likely intended to establish himself as controlling the rains and other elements central to successful agricultural growth, since he was ruling so soon after a famine (Ether 9:28–35).19 It would also have made ties back to important or founding ancestors, memorialized Riplakish in stone, and depicted him as seated between the earth and the supernatural or divine realm. Thus, by erecting a beautiful throne Riplakish positioned himself as both a political and a religious leader.

Riplakish’s effort to portray himself as a great leader and spiritual guide was boldly denounced by the prophet Ether, who said “Riplakish did not do that which was right in the sight of the Lord” (Ether 10:5). It did not fool his people either. After reigning for 42 years, “the people did rise up in rebellion against” Riplakish, and he “was killed, and his descendants were driven out of the land” (Ether 10:8). When this happened, Riplakish’s throne may have been defaced and mutilated to delegitimize his successors, as was typical when an Olmec ruler was deposed.20

The book of Ether’s overall portrayal of the construction of an elegant and elaborate throne very early in ancient American history is entirely correct, even though, as John E. Clark put it, “American prejudices against native tribes in Joseph’s day had no room for kings or their tyrannies.”21 This led Clark to ask, “How did Joseph Smith get this detail right?”22 However one wishes to answer that question, the study of early pre-Columbian thrones sheds considerable light on the story of Riplakish.

Further Reading

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 515–518.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:269–273.

John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2005): 45–46.

- 1. Other Jaredite kings also sat upon a “throne” though none others are described as “exceedingly beautiful” or particularly elaborate. See Ether 7:18; 9:5–6; 14:6, 9.

- 2. Jaredite chronology lacks any solid external dating, so the dating of events is difficult and opinions vary widely. David Palmer dates Riplakish’s reign to ca. 2020 BC, and John Sorenson dates it to 1900 BC, while John Clark and Joseph Allen both date it to around 1200 BC, and Brant Gardner dates it to sometime close to 800–770 BC. See David A. Palmer, In Search of Cumorah: New Evidence for the Book of Mormon from Ancient Mexico, 2nd edition (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 1999), 128; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 515; John E. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (2005): 46; Joseph L. Allen and Blake J. Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, revised edition (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2011), 120; Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:273.

- 3. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” 46.

- 4. See Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” 48. See also Joel W. Polka, “Olmec,” in The A to Z of Ancient Mesoamerica (Lenham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2010), 92–93. For more on connections between the Olmec and the Jaredites, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Book of Mormon Include the Rise and Fall of Two Nations? (Ether 11:20–21),” KnoWhy 245 (December 5, 2016).

- 5. John E. Clark and Arlene Colman, “Time Reckoning and Memorials in Mesoamerica,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 18, no. 1 (2008): 97. Mary Miller and Karl Taube, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 165 dates the earliest thrones to “around 1200 BC.”

- 6. See examples in Mary Ellen Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica: From Olmec to Aztec, 5th edition (New York, NY: Thames and Hudson, 2012), 38–39.

- 7. Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica, 38.

- 8. David C. Grove, “The Middle Preclassic Period Paintings of Oxtotitlan, Guerrero,” FAMSI, online at http://www.famsi.org/research/grove/index.html; see also David C. Grove, “Olmec Altars and Myths,” Archaeology 26 (1973): 128–135.

- 9. Christopher A. Pool, Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 10. Large thrones (previously mislabeled as “altars”), possibly portraits memorializing the former king, were also recarved into the famed Olmec colossal heads. See James B. Porter, “Olmec Colossal Heads as Recarved Thrones: ‘Mutilation,’ Revolution, and Recarving,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 17–18 (Spring–Autumn 1989): 23–30. For example, Monuments 2 and 53 from San Lorenzo are, according to Ann Cyphers, “clearly recarved from thrones.” Ann Cyphers, “From Stone to Symbols: Olmec Art in Social Context at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán,” in Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica, ed. David C. Grove and Rosemary A. Joyce (Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1999), 163. See also Pool, Olmec Archaeology, 121; Richard E. W. Adams, Prehistoric Mesoamerica, 3rd edition (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2005), 69–70.

- 10. Pool, Olmec Archaeology, 10.

- 11. Adams, Prehistoric Mesoamerica, 86.

- 12. Mary E. Pye, “Themes in the Art of the Preclassic Period,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mesoamerican Archaeology, ed. Deborah L. Nichols and Christopher A. Pool (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), 800.

- 13. Porter, “Olmec Colossal Heads as Recarved Thrones,” 24.

- 14. Clark and Colman, “Time Reckoning,” 96; Pool, Olmec Archaeology, 10.

- 15. Guersney describes the Olmec-style throne at Oxtotitlan, Mexico as “a celestial throne,” depicting a ruler “engaged in supernatural communion through a cosmic portal symbolized by the quatrefoil opening.” Julia Guernsey, Ritual and Power in Stone: The Performance of Rulership in Mesoamerican Izapan–style Art (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2006), 80.

- 16. Susan D. Gillespie, “Olmec Thrones as Ancestral Altars: The Two Sides of Power,” in Material Symbols: Culture and Economy in Prehistory, ed. John E. Robb (Carbondale, IL: Center for Archaeological Investigations, 1999), 224–253.

- 17. Guernsey, Ritual and Power in Stone, 80–81. This is because they were thought of as symbolic caves—places from which the rains were thought to come in Mesoamerican thought.

- 18. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Snakes Infest Jaredite Lands During a Famine? (Ether 9:30),” KnoWhy 243 (December 1, 2016).

- 19. Kerry Hull, personal communication to Book of Mormon Central staff.

- 20. Grove noted that “some Olmec-style ‘monument mutilation’ may have taken place at a leader’s death.” David C. Grove, “Chalcatzingo: A Brief Introduction,” PARI Journal 9, no.1 (2008): 3. See also David C. Grove, “Olmec Monuments: Mutilation as a Clue to Meaning,” in The Olmec and Their Neighbors: Essays in Honor of Matthew W. Stirling, ed. Elizabeth P. Benson (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1981), 49–68; Pool, Olmec Archaeology, 120–121. There is good evidence of Olmec monument mutilation occurring within some of the proposed time ranges of Riplakish that were done by the ruler’s people. Olmec specialist Michael Coe has stated: “Towards the end of the San Lorenzo phase [1150–900 BC] all of the great basalt monuments of San Lorenzo had been mutilated. . . . I take this to have been a revolutionary act, for we have no evidence that it was any other than San Lorenzo people themselves who carried out that great act of destruction.” Michael D. Coe, “Solving a Monumental Mystery,” Discovery 3, no. 1 (1967): 25.

- 21. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” 45.

- 22. Clark, “Archaeology, Relics, and Book of Mormon Belief,” 46.

Continue reading at the original source →