The Know

After arriving in the Promised Land, Nephi records that his father, Lehi, instructed and blessed his posterity shortly before passing away (2 Nephi 1:1–4:12). Early Jewish literature is filled with many examples of what is sometimes called testamentary literature. Generally dating from 200 BC to AD 500, these “testaments” are modeled after Jacob’s last blessing and cursing of his sons in Genesis 49.

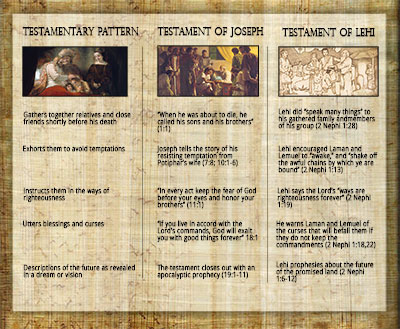

According to James H. Charlesworth, “No binding genre was employed by the authors of the testaments, but one can discern among them a loose format.” That format involves:

The ideal figure faces death and [1] causes his relatives and intimate friends to circle around his bed. He occasionally informs them of his fatal flaw and [2] exhorts them to avoid certain temptations; he typically [3] instructs them regarding the way of righteousness and [4] utters blessings and curses. Often he illustrates his words—as the apocalyptic seer in the apocalypse—with [5] descriptions of the future as it has been revealed to him in a dream or vision.1

This format can be easily demonstrated from several of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, which are among the earliest examples of testamentary literature.2

Take for example, the Testament of Joseph, who was one of the twelve patriarchs of Israel.

- The introduction says, “A copy of the testament of Joseph. When he was about to die, he called his sons and his brothers…” (1:1),3 proceeding from there to give lengthy instruction.

- The patriarch Joseph tells, at length, the story of his resisting temptation from Potiphar’s wife, occasionally adding specific warnings and exhortations about sin (e.g., 7:8; 10:1–6).

- His narrative is also laced with many instances of righteous instruction, such as his counsel, “in every act keep the fear of God before your eyes and honor your brothers” (11:1; cf. 2:4–7; 3:4; 4:3, 6; 9:3; 10:1–6; 11:1–7; 17:2–8).

- He also promises blessings, saying, “If you live in accord with the Lord’s commands, God will exalt you with good things forever” (18:1, the blessings continue throughout 18:1–4).

- Finally, the testament closes out with an apocalyptic prophecy (19:1–11).

These can each be seen, albeit sometimes only subtly, in Genesis 49.4 This same format can also be found in Lehi’s testament.

1. Gathers together relatives and close friends shortly before his death. Nephi says Lehi did “speak many things” to his gathered family and members of his group. This included Laman, Lemuel, their posterity, Sam, the sons of Ismael, Zoram, Nephi, Jacob, and Joseph (2 Nephi 1:28; 2:1; 3:1; 4:1, 3, 9–11).

It is clear throughout his discourses that he is about to die, as he frequently speaks of how he “must soon lay down in the cold and silent grave” (2 Nephi 1:14; cf. 1:21; 2:30; 4:5). Nephi confirms, “after my father, Lehi, had spoken unto all his household … he waxed old. And … he died, and was buried” (2 Nephi 4:12).

2. Exhorts them to avoid temptations. Lehi lectures his older sons about “their rebellions upon the waters” (2 Nephi 1:2). He encourages them to “awake,” and “shake off the awful chains by which ye are bound” (2 Nephi 1:13) and “observe the statutes and the judgments of the Lord” (2 Nephi 1:16). He warns them of the consequences if they fail to keep the commandments (2 Nephi 1:20; 4:4). He counsels all his posterity to “not choose eternal death, according to the will of the flesh” (2 Nephi 2:29).

3. Instructs them in the ways of righteousness. Lehi speaks of the Lord, saying “his ways are righteousness forever” (2 Nephi 1:19) and encourages his sons to “put on the armor of righteousness” (2 Nephi 1:23). He teaches them the plan of salvation (2 Nephi 2), and instructs, “I would that ye should look to the great Mediator, and hearken unto his great commandments; and be faithful unto his words, and choose eternal life, according to the will of his Holy Spirit” (2 Nephi 2:28).

4. Utters blessings and curses. Lehi speaks of blessings and curses throughout his discourse. He warns Laman and Lemuel of the curses that will befall them if they do not keep the commandments (2 Nephi 1:18, 22) and leaves them a conditional blessing (2 Nephi 1:28–29). He also blesses Zoram (2 Nephi 1:30–31), Jacob (2 Nephi 2:3–4), and Joseph (2 Nephi 3:3, 25). For the children of Laman and Lemuel, he pronounces a blessing on them while cursing their parents (2 Nephi 4:5–9).

5. Descriptions of the future as revealed in a dream or vision. Lehi begins, “I have seen a vision, in which I know that Jerusalem is destroyed” (2 Nephi 1:4). Lehi then prophesies about the future of the promised land (2 Nephi 1:6–12). He also shares an extensive prophecy from Joseph of Egypt describing many future events (2 Nephi 3). According to Lehi,

Joseph truly saw our day. And he obtained a promise of the Lord, that out of the fruit of his loins the Lord God would raise up a righteous branch unto the house of Israel; not the Messiah, but a branch which was to be broken off, nevertheless, to be remembered in the covenants of the Lord that the Messiah should be made manifest unto them in the latter days, in the spirit of power, unto the bringing of them out of darkness unto light—yea, out of hidden darkness and out of captivity unto freedom. (2 Nephi 3:5, emphasis added)

Lehi also says that Joseph prophesied about restoring the House of Israel (2 Nephi 3:13, 24).

Interestingly, in the Armenian version of the Testament of Joseph, Joseph was said to have prophesied that a portion of Israel “cried out to the Lord, and the Lord led them into a fertile, well-watered place. He led them out of darkness into Light” (19:3). From there, the patriarch sees the gathering of Israel (19:4–7). As in Lehi’s account, the Greek version of the Testament of Joseph indicates that Joseph knew of the coming Messiah and that the Messiah would not be from his own posterity, but Judah’s (19:8).

The Why

This comparison is interesting for multiple reasons. First, it illustrates that in some ancient Jewish traditions, it was normal and expected that the patriarch of the family would gather together his family and bless, instruct, exhort, and prophesy to them before passing away. In this, Lehi’s behavior was as expected.5

Second, it illuminates Lehi as the patriarch of a new, separate branch of Israel. While not all, many of the figures in testamentary literature are patriarchal figures from Israel’s past. In portraying Lehi in this role, Nephi is solidifying the Lehites as an independent branch of Israel. This was a lasting legacy among Book of Mormon peoples. John W. Welch has explained,

Seeing Lehi in the patriarchal tradition is borne out by the fact that Lehi was remembered by Nephites from beginning to end as “father Lehi.” … Since Lehi is the only figure in the Book of Mormon called “our father,” this designation appears to be a unique reference to Lehi’s patriarchal position at the head of Nephite civilization, society, and religion.6

Third, it is interesting that in both Lehi’s discourse and the Testament of Joseph, Joseph seems to prophesy of a portion of Israel being broken off and led to a land of promise, the gathering of Israel, and the Messiah from the tribe of Judah. The prophecy cannot currently be traced back to Lehi’s time, let alone all the way back to Joseph of Egypt. Yet, this comparison illustrates that some well-documented ancient traditions are consonant with the Book of Mormon.

Finally, it provides an example for fathers and patriarchs today. The tradition, initially but briefly present in Genesis 49, was not maintained and developed only by the Jews after their return to Jerusalem in the Second Temple period but was called upon extensively and effectively by Lehi in the sixth century BC. Building from there, later prophets in the Book of Mormon followed Lehi’s example, as Alma does in Alma 36–42 and Helaman does in Helaman 5:5–13. Latter-day Saint fathers today also follow these patriarchal examples as they bless, instruct, exhort, and testify to their children and grandchildren.

Further Reading

John W. Welch, “Lehi’s Last Will and Testament: A Legal Approach,” in Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1989), 61–82.

- 1. James H. Charlesworth, Introduction to Testaments Section, in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2 vols., ed. James H. Charlesworth (Peabody, Mass.: Henrickson Publishers, 1983), 1:773, brackets added.

- 2. For background and translation of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs, see H.C. Kee, “Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1:775–828. All quotations will come from this edition.

- 3. All references to chapter and verse in the Testament of Joseph.

- 4. In Genesis, Jacob (1) "called unto his sons" to gather together (49:1-2); (2) his words to Reuben warn against instability (49:4), and his words to Simeon and Levi condemn "cruelty," murder, anger, and wrath (49:5–6); (3) he speaks of waiting for the Lord's salvation (49:18) and his words to Joseph illustrate the blessings of leaning on the strength of "the mighty God of Jacob," and the "stone of Israel" (49:24); (4) the bulk of the chapter is blessings (49:8–12, 13, 19–26, 28) and cursings (49:4, 7, 15); (5) All his words to his sons are about "that which shall befall you in the last days" (49:1), but the blessings to both Judah (49:8–12) and Joseph (49:22–26) are particularly prophetic.

- 5. While the testamentary literature is from a period later than Lehi’s own day, it ultimately stems from Genesis 49, which could have been on the brass plates. Both the Nephites and the later Jews may have developed "testament" traditions independently based upon Genesis 49 as a model.

- 6. John W. Welch, “Lehi’s Last Will and Testament: A Legal Approach,” in Second Nephi, The Doctrinal Structure, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1989), 69–70.

Continue reading at the original source →