The Know

Several passages in the Book of Mormon speak of eternal torment in a “lake of fire and brimstone [sulfur]” as the fate of sinners who die without having reconciled themselves to God. The prophet Jacob, brother of Nephi, for instance, assured that “as the Lord liveth . . . they who are filthy are the devil and his angels; and they shall go away into everlasting fire, prepared for them; and their torment is as a lake of fire and brimstone, whose flame ascendeth up forever and ever and has no end.”1 This teaching is verbalized by other Book of Mormon prophets, including Nephi (2 Nephi 28:23), King Benjamin (Mosiah 3:27), and Alma and Amulek (Alma 12:17; 14:14–15).2

Such language is found elsewhere in scripture. Genesis speaks of “brimstone and fire” raining down on Sodom and Gomorrah (Genesis 19:24; cf. Luke 17:29), while another text warns of God sending “fire and brimstone” upon the wicked (Psalm 11:6). In the New Testament the book of Revelation (which draws heavily on apocalyptic language from the Old Testament) uses “fire and brimstone” (14:10; 21:8) and “lake of fire and brimstone” (19:20; 20:10) to depict the torment of Satan and his followers. Although the Book of Mormon renders this phraseology in familiar King James English,3 the text's core teachings and underlying depictions accurately reflect very ancient Near Eastern perceptions and pre-Christian precedents.

For instance, Old Testament prophets repeatedly employ the metaphor of consuming fire to describe the judgments of God on wicked nations. One example is the prophet Isaiah’s vivid depiction of the Lord’s impending judgments on the kingdom of Assyria:

Behold, the name of the Lord cometh from far, burning with his anger, and the burden thereof is heavy: his lips are full of indignation, and his tongue as a devouring fire. . . . [T]he Lord shall cause his glorious voice to be heard, and shall shew the lighting down of his arm, with the indignation of his anger, and with the flame of a devouring fire, with scattering, and tempest, and hailstones. For through the voice of the Lord shall the Assyrian be beaten down, which smote with a rod. . . . For Tophet is ordained of old; yea, for the king it is prepared; he hath made it deep and large: the pile thereof is fire and much wood; the breath of the Lord, like a stream of brimstone, doth kindle it. (Isaiah 30:27, 30–31, 33, emphasis added)

This passage speaks of Tophet, which in Hebrew means essentially “a fire-place” or place of burning.4 In other words, the king of Assyria, according to this prophetic oracle, was ordained to suffer annihilation on, essentially, a burning pile of wood.5 Elsewhere in Isaiah wicked inhabitants of the earth are spoken of as being “burned” (Hebrew: ḥarah; “to be hot,” “kindle,”6) by the Lord in divine retribution for breaking the covenant (Isaiah 24:5–6). And, of course, the New Testament’s imagery of Gehenna (hell) as a place of fiery torment7 drew its inspiration from the Hebrew gêy ben hinnōm (that is, the Valley of the Son of Hinnom), the valley just south of Mount Zion in Jerusalem which was immortalized in the Old Testament as the infamous location of fiery child sacrifices to the god Moloch (2 Kings 23:10; 2 Chronicles 28:3; 33:6) and later as a smoldering garbage dump.8

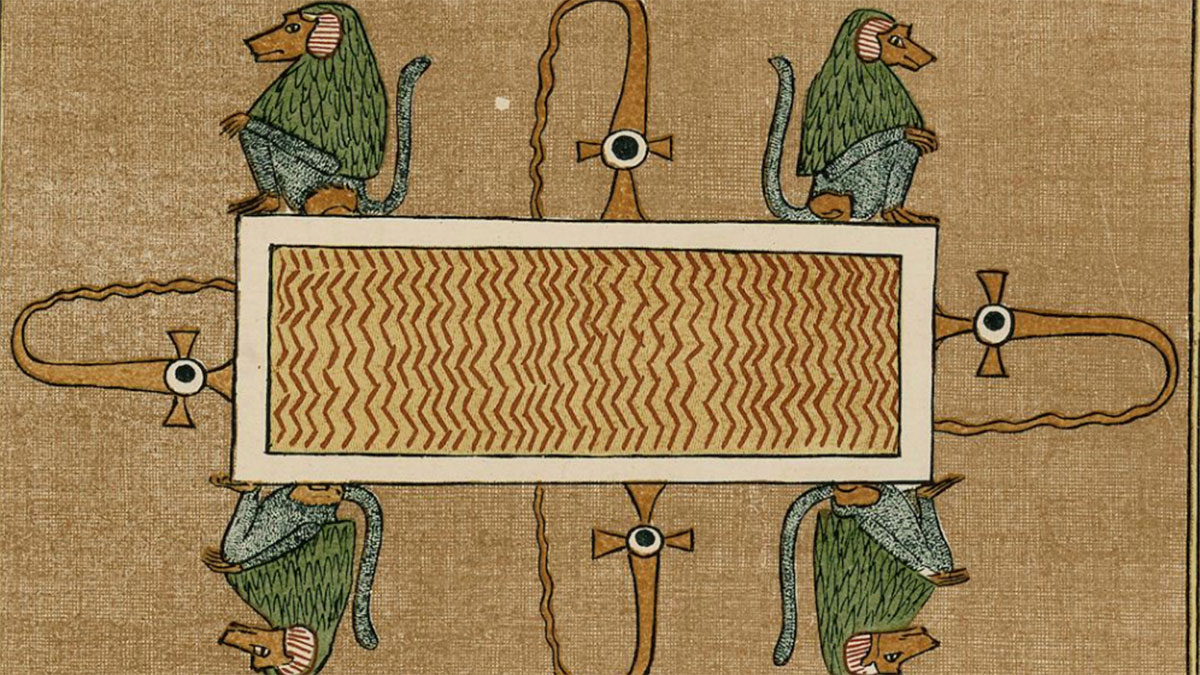

Significant convergences between the Book of Mormon’s description of hell are also found among the writings of the ancient Egyptians. The so-called netherworld books9 from the Egyptian New Kingdom (ca. 1540–1075 BC) contain shocking depictions of the fate awaiting those who are annihilated in the afterlife for failure to properly navigate the underworld. Punishments for the damned in the Egyptian afterlife include being burned alive by fire-breathing serpents, being roasted in fiery pits, and being cut up and cooked in cauldrons.10 Furthermore, the Egyptians imagined a “lake of fire”11 (Egyptian: mw n sḏt; “waters of fire”; š n ȝmw; “lake of burning”) that provided “fiery torture . . . for those who are to be punished and destroyed” in the afterlife.12 In iconographic depictions of the netherworld this lake of fire is drawn as “a rectangular or round body where the water is fire, suitably colored in red, or given red waves.”13

The consummate damnation described in the ancient Egyptian netherworld texts was total annihilation and non-existence. “The goal of all these punishments is to inflict not suffering itself, but rather complete elimination,” Egyptologist Erik Hornung writes. “The damned are thus frequently designated as ‘eliminated’ or ‘non-being’ and ‘negated.’ They are not, and they should not be: extinguishing their existence is the ‘second’ or ‘repeated death’ [Egyptian: mt m wḥm] frequently mentioned with fear in the Book of the Dead.”14 So grave were the consequences (everlasting annihilation) of the second death that the Egyptians composed funerary spells offering protection against such.15

The Why

As seen from the preceding evidence, the imagery used by the Book of Mormon to depict hell finds ample parallel in the ancient world.16 Nephi, with his background as a learned Israelite with training in Egyptian scribal practice (1 Nephi 1:2), may have drawn broadly from his ancient Near Eastern cultural backdrop in rendering his theological imagery. That imagery was then picked up and developed by subsequent Nephite prophets as they naturally found it compellingly graphic.17

More important than the linguistic expressions that scripture uses, however, is the eternal truth the Book of Mormon teaches that “this life is the time for men to prepare to meet God; yea, behold the day of this life is the day for men to perform their labors.” As the prophet Amulek stressed, it is vitally important that men and women “do not procrastinate the day of [their] repentance until the end; for after this day of life, which is given us to prepare for eternity, behold, if we do not improve our time while in this life, then cometh the night of darkness wherein there can be no labor performed” (Alma 34:32–33).18

While harsh and disturbing imagery of God destroying sinners with fiery torment may understandably be unsettling for modern readers, Latter-day Saints are especially blessed to know that the imagery of hell as a place of burning torture is meant to be understood only figuratively. Jacob spoke of this torment as being “as a lake of fire and brimstone” (2 Nephi 9:16, emphasis added). King Benjamin described the demands of divine justice as awakening the unrepentant soul “to a lively sense of his own guilt, . . . which is like an unquenchable fire, whose flame ascendeth up forever,” or in other words “never-ending torment” (Mosiah 2:38–39, emphasis added). In 1829, the Savior himself explained that “endless torment” is called endless because God is endless, and thus his punishment is called “endless” (Doctrine and Covenants 19:6–7). All who repent can escape those exquisite sufferings (D&C 19:16). The mercy extended through faith and repentance is such that even those who die without having had an opportunity to receive the gospel in mortality will have such afforded to them in the spirit world.19

To awaken our minds and hearts to the urgency of needing to repent, the scriptures make strong use of powerful metaphors and meaningful words and images. To those who take heed and give diligence, the generous Nephite record is “another testament concerning the existence of hell, and explains how one can escape the ‘chains of hell’ [Alma 5:7, 9-10] in this life, and an everlasting hell in the next life, through application of the Atonement of Jesus Christ.”20

Further Reading

Dennis L. Largey, “Hell, Second Death, Lake of Fire and Brimstone, and Outer Darkness,” in The Book of Mormon and the Message of the Four Gospels, ed. Ray L. Huntington and Terry B. Ball (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 77–89.

Larry E. Dahl, “The Concept of Hell,” in A Book of Mormon Treasury: Gospel Insights from General Authorities and Religious Educators, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2003), 262–79.

Monte S. Nyman, “The State of the Soul between Death and Resurrection,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, the Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 173–94.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does Jacob Choose a ‘Monster’ as a Symbol for Death and Hell? (2 Nephi 9:10),” KnoWhy 34 (February 16, 2016).

- 1. 2 Nephi 9:16; cf. vv. 19, 26; Jacob 3:11; 6:10.

- 2. For an overview of this teaching in the Book of Mormon, see Dennis L. Largey, “Hell, Second Death, Lake of Fire and Brimstone, and Outer Darkness,” in The Book of Mormon and the Message of the Four Gospels, ed. Ray L. Huntington and Terry B. Ball (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 77–89.

- 3. The similar scenes described in the book of Revelation and in Nephi’s writings may well be attributable to Nephi having seen the things which the apostle of the Lamb and other ancient seers would also be shown (1 Nephi 14:24, 26). For a discussion see Brant A. Gardner, The Gift and Power: Translating the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2011), 307–308.

- 4. Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 2:1781.

- 5. See the commentary in Philip C. Schmitz, “Topheth,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6:601. Note also the observation made by Joseph Blenkinsopp, who writes that this passage “concludes with the ritual immolation [burning] of Assyria in the Valley of Hinnom, later Gehenna.” Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39, The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 424.

- 6. Koehler and Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, 1:351.

- 7. Matthew 5:22, 29–30; 10:28; 18:9; Mark 9:43, 45, 45; Luke 12:5; James 3:6.

- 8. See Duane F. Watson, “Hinnom Valley,” in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, 3:202–203. Biblical scholars dispute to what degree these passages describe actual, historical human sacrifices as opposed to act as polemical rhetoric against unpopular Judahite kings such as Ahaz and Manasseh. See the recent discussions presented in Francesca Stavrakopoulou, King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2012); Heath D. Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2017). Whatever the case may be, the recognition of the Valley of Hinnom as a place of fiery death and destruction in Israelite religious consciousness is attested in texts contemporaneous to Lehi and Nephi (Jeremiah 7:31–32; 19:2–6, 11–14; 32:35).

- 9. Ancient Egyptian beliefs about the afterlife spanned millennia. The earliest corpus of texts describing how the Egyptians conceived of the afterlife are the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2705–2180 BC), followed by the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom (ca. 1987–1640 BC), followed by the Book of the Dead, the Book of Gates, the Book of Caverns, the Book of the Amduat, and other similar compositions in the New Kingdom (ca. 1540–1075 BC), and the Book of Breathings in the Ptolemaic Period (ca. 350–30 BC). During Egypt’s history some beliefs and traditions about the nature of the afterlife diminished over time while others remained popular, with elements from the Pyramid Texts or the Coffin Texts sometimes surviving many centuries past their initial composition and resurfacing in texts from the New Kingdom, such as the Book of the Dead. For an accessible overview of these texts, their transmission, and their significance in ancient Egyptian religion, see Erik Hornung, The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife, trans. David Lorton (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999).

- 10. See the extended discussions with ample textual citations and examples in J. Zandee, Death as an Enemy According to Ancient Egyptian Conceptions (Leiden: Brill, 1960); Erik Hornung, Altägyptische Höllenvorstellungen (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1968); “Black Holes Viewed from Within: Hell in Ancient Egyptian Thought,” Diogenes 165, no. 42/1 (Spring 1994): 133–156.

- 11. So translated routinely by Egyptologists, including Hornung, Altägyptische Höllenvorstellungen, 22.

- 12. Hornung, “Black Holes Viewed from Within,” 142. See further Hornung, Altägyptische Höllenvorstellungen, 21–29

- 13. Hornung, “Black Holes Viewed from Within,” 142. See also the discussion in Eltayeb Sayed Abbas, The Lake of Knives and the Lake of Fire: Studies in the Topography of Passage in Ancient Egyptian Religious Literature, BAR International Series 2144 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2010). Spell 149 from the Book of the Dead contains this description of the lake of fire: “Its water is fire, its waves are fire, its breath is efficient for burning, in order that no-one may drink its waters to quench their thirst, that being what is in them, because their fear is so great and so towering is its majesty. Gods and spirits see its water from afar, but they cannot quench their thirst and their desires are unsatisfied.” Raymond O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: 189 Spells, Prayers and Incantations for the Afterlife (Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2010), 144.

- 14. Hornung, “Black Holes Viewed from Within,” 145. Compare this with the teaching of Book of Mormon prophets that a “second death” (also called a “spiritual death” and an “everlasting death”) awaits unrepentant sinners (Jacob 3:11; Alma 12:16, 32; 13:30; Helaman 14:18–20).

- 15. See Zandee, Death as an Enemy, 186–188, who catalogues multiple Egyptian funerary spells offering the following protections: “Not to die for the second time”; “He who knows this spell does not die for the second time”; “Not to die for the second time in the realm of the dead.” Zandee even goes so far as to compare this phraseology to that found in Revelation 2:11; 20:6; 21:8. Further commentary can be found in Jan Assmann, Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt, trans. David Lorton (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2001), 64–86.

- 16. Zandee, Death as an Enemy, 303–342, examines how earlier “pagan” Egyptian conceptions of hell and the afterlife may have influenced Coptic (Egyptian) Christianity. See further John Gee, “Some Neglected Aspects of Egypt’s Conversion to Christianity,” in Coptic Culture: Past, Present and Future, ed. Mariam Ayad (Stevenage, UK: The Coptic Orthodox Church Centre, 2012), 43–55. Blogger Clark Goble offers the intriguing idea that a large volcano near Jerusalem (Al Safa in modern Syria) might also have inspired Nephi’s metaphor of hell being a “lake of fire and brimstone.” Clark Goble, “Hell Part 2: Lake of Fire and Brimstone,” Times and Seasons (February 23, 2018). Alternatively, any of the known active volcanos in Mesoamerica may have provided the inspiration for Nephi’s imagery.

- 17. See also “Why Does Jacob Choose a ‘Monster’ as a Symbol for Death and Hell?” KnoWhy #34 (2016).

- 18. Another interesting parallel with the Book of Mormon is the ancient Egyptian belief that lurking in the underworld was an oppressive, abysmal darkness ready to consume the damned, who in one text are condemned as “those who do not see [the sun god] Re’s rays, and do not hear his words. They are in darkness, and their souls do not leave the earth, and their shades do not alight on their bodies.” Hornung, “Black Holes Viewed from Within,” 135, 137–138, 142, 150–153, quote at 138.

- 19. 1 Peter 3:18-20; D&C 128:15–18; 137:7–10; 138:25–37.

- 20. Largey, “Hell, Second Death, Lake of Fire and Brimstone, and Outer Darkness,” 88.

Continue reading at the original source →