The seal of Melchizedek as seen on the entrance doors of the Salt Lake Temple. (Click for larger view)

It’s been a long time coming, since September 2008 to be exact, and I’d like to finally complete this series of posts on the seal of Melchizedek. It is probably one of the most trafficked series of posts on this website. It’s drawn a lot of attention, and may have even been part of what compelled a BYU scholar, Alonzo L. Gaskill, to publish an article about it in The Religious Educator at BYU in 2010, which article I’d like to talk about.

But first, there are a few other artifacts related to the symbol that I’d like to share. As I pointed out in Part 2, this seal is most prominently found as displayed in the mosaics and iconography in the basilicas of Ravenna, Italy. Indeed, this is very likely where Hugh Nibley saw this symbol originally, as perhaps did Michael Lyon, and where he may have coined the name the “seal of Melchizedek.” The symbol is shown on the altar cloths in these mosaics, shown next to Melchizedek, Abel, and Abraham, in making sacrificial offerings to God. The altar cloth also shows gammadia in the corners, right-angle marks like the Greek letter gamma, which is also very interesting, and worthy of a study in and of itself.

To begin, I want to note again that to date I have not found any evidence for this symbol being called the “seal of Melchizedek” by any other scholar, historian, or historical figure in recorded history before Hugh Nibley and Michael Lyon. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, but it is likely a conception that began with the Latter-day Saints, making a logical connection between the symbol and the Biblical figure found adjacent to it in the mosaics.

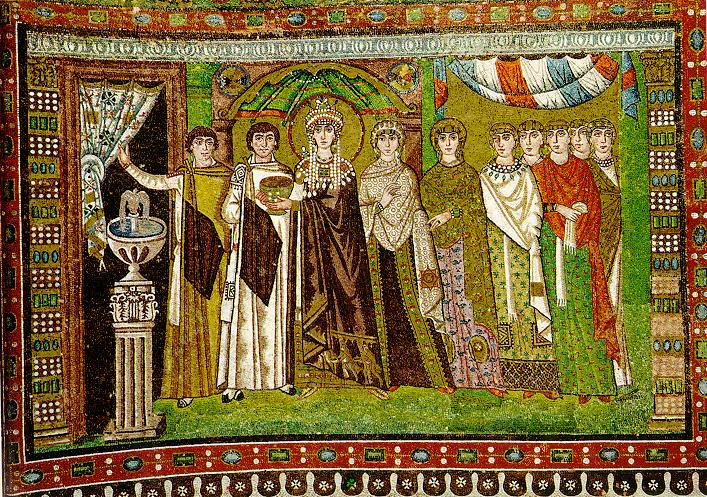

In my investigation of the seal of Melchizedek back in 2008, I came across some other depictions of this symbol anciently. One was in the mosaic “Theodora’s Procession with Retinue” from San Vitale, one of the same basilicas where the other seals are located.

Theodora’s Procession with Retinue, San Vitale basilica, Ravenna, Italy.

Princess Julia Anicia garment closeup, showing the seal of Melchizedek

In addition to showing a veil being parted on the left, possibly representing the veil of the temple, and entrance to the Holy of Holies, the woman immediately to the left of Theodora is likely the royal Princess Julia Anicia. On the lower portion of her garment is prominently seen the same seal of Melchizedek, perhaps indicating her royal status.

It is interesting that Theodora in this image is carrying a chalice, one commentator noting that it may represent Christ’s sacrificial blood, yet also notes that this is “problematic because only a priest should be so consecrated to minister herein.”

The symbol is found in more than just Christian iconography. Another place I found this symbol prominently displayed is in the Muslim world. There it has become known as the Rub el Hizb, and is dominantly used on many Muslim emblems and flags. Wikipedia notes that it may be originally found in the Quran, and to mark the end of a chapter in Arabic calligraphy. Indeed, it is even included as part of the vast Unicode family of characters, ۞ at U+06DE. It is also noted that the symbol may have represented Tartessos, an ancient civilization based in Andalusia.

For Islam it is also known as the al-Quds star, i.e. Jerusalem star, and may have ties to the octagonal ground-plan of the Dome of the Rock. Furthermore in Islam, this symbols is also related to Muhammad himself, in the form of the Khātam al-Nabiyyīn, or “Seal of the Prophets,” which designates him in Muslim belief as the last of the prophets to reveal God’s divine message. It is likely that Professor Daniel C. Peterson knows much more of this symbol’s use in Muslim culture. More can be read at MoroccanDesign.com.

Again, the symbol is also found in Hinduism, where it is known as the Star of Lakshmi, and where it represents Ashtalakshmi, the eight forms, or “kinds of wealth”, of the goddess Lakshmi. The geometry of the symbol is intricately noted in mathematical formulas here, a subject which Nibley explored quite a bit in his last magnum opus One Eternal Round.

Another place we find the eight-pointed star is none other than in Freemasonry, and this time it is directly associated with Melchizedek. As Tim Barker has found in his post on the subject (as well this excellent overview by Tim), Henry Pelham Holmes Bromwell published a book in 1905 which extrapolates an eight-pointed star from Euclidean geometry, which Bromwell notes in the caption is called the “Signet of Melchizedek”1. While not exactly the same as the two interlocking squares that we’ve come to know as the seal of Melchizedek, this eight-pointed star certainly approximates the same shape. Unfortunately, Bromwell fails to explain how the shape has a connection to Melchizedek.

Likely the original source of the name “seal of Melchizedek” is the caption by Michael P. Lyon on the photo of the mosaic from the Basilica of St. Apollinaire in Classe in Ravenna, Italy, as shown in Nibley’s book Temple and Cosmos. Since that is where the name most probably originated, speaking with Michael Lyon on the subject would possibly illuminate some things, which is precisely what Tim Barker has done, as documented on his blog LDS Studies. Lyon recalls that it may have been Nibley who inserted the words “so-called” before the term “seal of Melchizedek,” perhaps indicating his hesitancy at the name. Yet Lyon notes that he believes it was another scholar, sometime after the creation of the mosaics, that may have linked the symbol to Melchizedek, and called it the “seal of Melchizedek,” perhaps in a 19th century book on Catholic symbolism. This is the missing link that no one, including Lyon, has been able to find or confirm.

Of course, where would we be without making a connection back to Egypt. Ancient Egyptian Coptic textiles have been discovered which mirror very closely the symbols in the Ravenna mosaics. Indeed, the Ravenna mosaics may have been the result of intermingling with Egyptian culture, or originated directly from the Christians in Egypt. A book entitled Catalogue of textiles from burying-grounds in Egypt by Albert Frank Kendrick published in 1920 is very instructive relative to these textiles, and is freely available for download from Google Books. What is also fascinating is that Kendrick also connects the gammadia on the Ravenna mosaic altar cloths with the gammadia found on Egyptian Coptic garments (which Tim Barker also notes well):

Early altar-coverings, as represented in mosaics and illuminated MSS., often had this form of decoration, and it is also to be found quite frequently in reliefs and stone carvings. The resemblance to the Greek letter gamma has given to cloths thus ornamented the name of gammadion, gammadije, or gammidae….

With regard to the form and decoration of the garments, comparisons with representations in mosaics, paintings, and carvings prove conclusively that those worn in Egypt were not peculiar to that country…

The two famous mosaics in the church of S. Vitale, representing the Emperor Justinian (d. 565) and his queen Theodora, with attendants, are a very valuable record of the costume and ornaments of the time… The tunics and mantles of the women on the Empress’s left have square, star-shaped and circular panels, and some are covered with small diaper patters… A mosaic in S. Vitale, representing the Sacrifices of Abel and Melchizedek, shows an altar-covering with angular ornaments, and a large eight-pointed star in the middle. Numerous ornamental details of the mosaics at Ravenna also resemble in a remarkable way the more elaborate patterns of the stuffs from Egypt… It should also be remembered that, although none of the Ravenna mosaics are earlier than the fifth century, many of the ornamental details were survivals of patterns used at an earlier date.”2

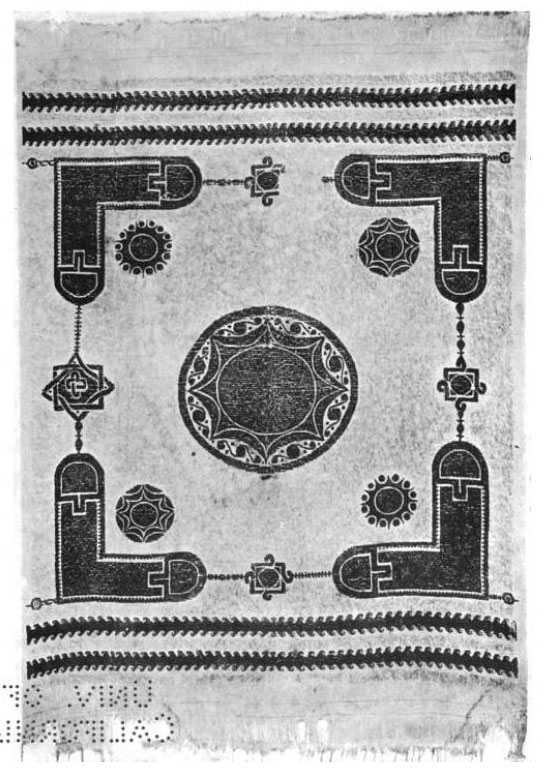

Below is one Coptic textile that is the most striking, as it is almost identical in form to the altar cloth found in the Ravenna mosaics, shown in the frontispiece of Kendrick’s study, but includes several other eight-pointed stars as well. It is one of the largest (approx. 9′ 6″ long and 6′ 3″ wide) and most well preserved of such cloths in existence, at least in 1922, and may be located at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It dates from Akhmim, 3rd-4th century, and Kendrick notes it could have served as an altar cloth, or some sort of curtain or hanging (veils?), as well as a garment to be worn:

It is the garment corresponding to the pallium that we find in Egypt. There it may even have had other uses, as a curtain or hanging. The question has been often debated whether the fine big cloths found in Egypt were really used in life as garments. They are oblong in shape, one entire specimen in the Museum (No.6), measuring 9 ft. 6 in. by 6 ft. 3 in.’ The probable explanation is that many of them served a variety of uses, like the Roman toga; and as a matter of convenience, the large cloths, whether garments or hangings, are described together here and in other sections of the catalogue. Figures and reliefs provide ample proof that cloaks were worn in Egypt over the tunic. These would be peculiarly suitable for a wrapping at burial [at burial!], and we need have no hesitation in assuming that such garments are to be identified among these cloths from the graves…

An outstanding feature of the decoration of a number of large cloths in the Museum is the characteristic border composed of four ornamental right-angles [gammadia, from the Greek letter gamma]. This ornamentation would be very suitable for floor-coverings; and it is easy to show that it was applied to curtains and hangings; but that it was also used on cloaks is made clear by the decoration of certain mummy-cases, where it is seen on the shoulder.3

Coptic Egyptian textile, with gammadia in the four corners, and eight-pointed star in the center

While there appears to be little that connects Melchizedek to the eight-pointed star symbol beyond the few mosaics in Ravenna, Italy, it still remains that Melchizedek was an enigmatic figure in the Old Testament, and much remains to be learned about him. Here are some of my thoughts as I have discussed this with others, including gleaning some from Margaret Barker’s work on Melchizedek (who, in passing, told me that she hasn’t published any thoughts about this symbol, other than considering it might be linked to “Wisdom,” which is another interesting subject I might explore in a future post).

Melchizedek is an interesting Biblical figure, and Joseph Smith certainly revealed more of this important character in this dispensation. I feel that the term may be more of a title than a name, although the historical Biblical character clearly became known by that name. It is almost as if Melchizedek is the title, or new name, of one who has become a Son of God (cf. JST Heb. 7:3). Those who become heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ become Kings and Priests of Righteousness too, or just like a “Melchizedek.” Indeed, Christ is said to be after the order of Melchizedek forevermore (Hebrews 5:6). In essence, Christ has become a Melchizedek, a King of Righteousness, a King of peace, a Prince of peace, just like we can become when we obtain a fulness of the Melchizedek priesthood.

Here’s another thought, could Melchizedek have been a pre-Mosaic name for Christ, the pre-mortal Jehovah, or Yahweh? I’ve noticed that the phrase “most high God” (El Elyon) seems to be used almost exclusively in Genesis, and there only in the passage stating that Melchizedek was a priest of the “most high God” (Gen. 14:18). In earlier chapters the term “LORD God” or “Yahweh Elohim” is used, but not in this passage. It is also interesting that directly after stating that Abram gave tithes of all to Melchizedek, Abram states, “I have lift up mine hand unto the LORD, the most high God, the possessor of heaven and earth…” (Gen 14:22). Did Abram give tithes and make covenants with Melchizedek, or Yahweh, or the most high God, or could they all be considered one in the same at that point? (The phrase “possessor of heaven and earth” in this verse is also insightful as relating to the symbols of the circle and square, as explained below). BYU religion scholar Andrew Skinner notes in his book Temple Worship that the Israelites lost the privilege of having a knowledge of the “most high God” or God the Father during the Mosaic dispensation. Could the name of Melchizedek have been lost during that time, referring only to Yahweh, God the Son? Clearly, if Melchizedek was a high priest acting in God’s stead he was acting with divine investiture of authority, and so these things are hard to determine precisely. But they are interesting to ponder.

A friend of mine, and a fantastic scholar, Jeffrey Mark Bradshaw, who wrote the tome In God’s Image & Likeness (which is remarkable in regards to temple studies), had this exquisite thought about what might be the meaning of this eight-pointed symbol that we’ve coined the “Seal of Melchizedek”:

Since we don’t have much in the way of texts we can draw on, maybe another tack is to think about the symbol itself. We do know something about gammadia in a priesthood context, and although we don’t know much about the completion and interconnection of gammadia into the eight-pointed star, we do know something about how the circle and square are combined, and their joint meaning in this context.

To me, the intersection of the circle and square are most satisfactorily explained in terms of the coming together of heaven and earth in both the sacred geometry of the temple and the soul of the seeker of Wisdom4, which might be equated to the culminating blessings that follow as an eventual consequence of having received a fulness of the Melchizedek Priesthood.

In Buddhist thought, the center of the mandala may be seen as an undimensioned point of origin, the divine "essence" toward which the outer circumferences of the figure grasp5 (e.g., "The shape, with its focus on the circle (referring to the heavens) and the square (referring to the earth), forms the foundation of the traditional view that the cosmic ritual structure brings heaven and earth together. In this place the initiate confronts and achieves union with the divine realm"6.) The fully-rendered figures of the circle and the square manifest in their completeness what the tools of the compass and the square symbolize only in anticipation.7

Which brings us back to the article by Alonzo Gaskill in The Religious Educator on the subject of “The Seal of Melchizedek?” Gaskill finds the symbol lacking in its explicit relationship to Melchizedek, as do I. But I am of the opinion, as is Tim Barker and others, that symbols are what we make of them, since they are flexible representations of the people who view and use them. As Tim noted:

If there were no ancient connection with Melchizedek and the eight-pointed star, is it wrong for us as Latter-day Saints to adopt the eight-pointed star as the seal of Melchizedek? Brother Gaskill feels that if anything, it should only represent the Savior. While I agree that it should represent the Savior, I personally see nothing wrong with associating this symbol with Melchizedek, who might be the person who most strongly symbolizes the Savior. Gaskill asserts that the symbol never has “anything to do with Melchizedek or the Melchizedek Priesthood,” and that “there is nothing ancient or scholarly to support such a connection.” He stated that the “unknown artist of the murals left no known explanation of his objective,” and further declares that he has “established that there is nothing in scholarly or ancient sources to support the interpretation that this symbol represents Melchizedek or his priesthood…”8

If the Latter-day Saints want to ascribe this symbol as a representation of Melchizedek, his Priesthood, and therefore after the order of the Son of God (D&C 107:3), our Savior Jesus Christ, and call it the “Seal of Melchizedek,” then why not? That’s what symbols are.

The Seal of Melchizedek – Part 5

Notes:- Henry Pelham Holmes Bromwell, Restorations of Masonic Geometry and Symbolry Being a Dissertation on the Lost Knowlege of the Lodges, (H.P.H. Bromwell Masonic Publishing Company, Denver, CO, 1905), 170.

- Kendrick, Catalogue of Textiles from Burying-grounds in Egypt, 32-38

- ibid., pg. 31-33

- J. M. Lundquist, “Fundamentals of temple ideology from Eastern Traditions,” In Reason, Revelation, and Faith: Essays in Honor of Truman G. Madsen, edited by Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson and Stephen D. Ricks, pp. 666-671

- M. G. Rje, Introduction to the Buddhist Tantric Systems, p. 270

- J. M. Lundquist, Fundamentals, p. 666

- Email, September 4, 2008. These thoughts are more thoroughly addressed by Bradshaw in his book, In God’s Image & Likeness, pgs. 571-74.

- Tim Barker, “Seal of Melchizedek – Eight-pointed Star,” LDS Studies.

Continue reading at the original source →